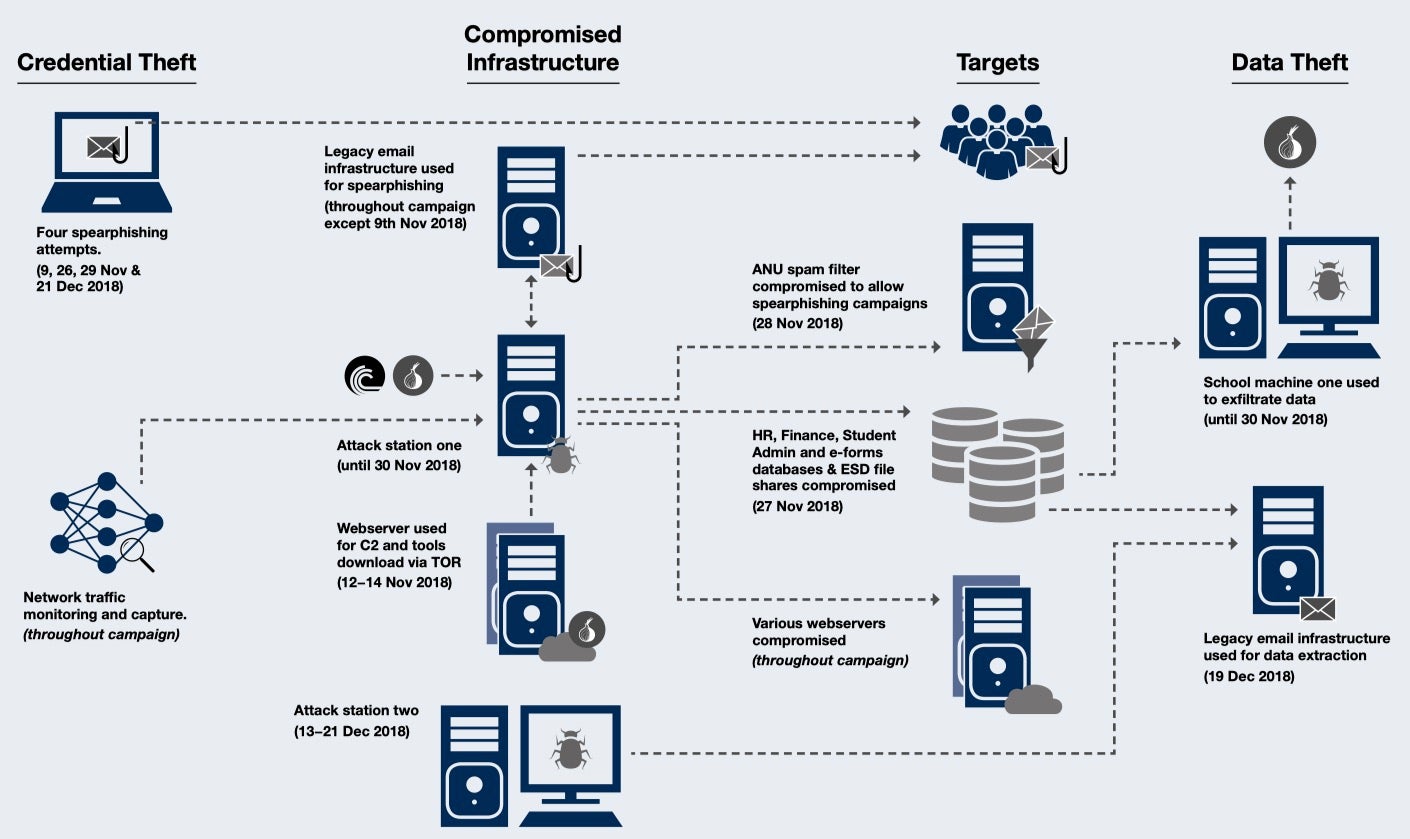

During November of last year, a highly-skilled — possibly nation state threat actor — penetrated the network of the Australian National University. The dwell time, or length of time the attacker went undetected, was around six weeks. Afforded such an extensive period of time, the actor engaged in lateral movement activities, downloaded bespoke malware, conducted further spearphishing campaigns and exfiltrated an unknown amount of data from a possible 19-year treasure trove of records from Human Resources, financial management and student administration. The details of the attack, discovered in June of this year, have recently been published by the university’s Office of the Chief Information Security Officer. In this post, and based on their thorough report, we review the major lessons every CISO can learn from the ANU cyber attack.

1. Don’t Wait Till It’s Too Late | Replace Legacy AV

Without doubt the most startling lesson for CISOs from the ANU breach is that you cannot wait to update your security if you want to match and defeat the skills of today’s threat actors.

ANU: “The actor was able to, in several cases, avoid detection by altering the signatures of more common malware used during the campaign. Also, the malware and some tools were assembled inside the ANU network after a foothold had been established. This meant that the downloaded individual components did not trigger the University’s endpoint protection.”

The old legacy AV suites that ANU had been using up until last year were no match for the attacker. Indeed, such systems are regularly bypassed by red team engagements, and bypasses are widely known and traded on hacker forums. Legacy AV suites afford very little protection against anything other than accidental or amateur intrusion attempts and need to be replaced as quickly as possible.

2. Phishing Is King | Block Bad Behavior, Not Users

Users will always be susceptible to phishing and spearphishing attacks. Enterprises need to stop relying on human behavior to recognize phishing campaigns and instead rely on machine learning to detect and block malicious behaviour on endpoints.

ANU: “The actor’s campaign started with a spearphishing email sent to the mailbox of a senior member of staff. Based on available logs this email was only previewed but the malicious code contained in the email did not require the recipient to click on any link nor download and open an attachment. This “interaction-less” attack resulted in the senior staff member’s credentials being sent to several external web addresses.”

Let’s not blame the user, but there’s a reason why phishing was used in the ANU attack and is by far the most common attack vector. People, unlike computers, need to get things done. But the attacker, like the victim, is also a human and to reach their objectives, the tools, tactics and procedures they use to achieve those objectives can be modelled behaviorally.

A no-interaction phishing email raises interesting and worrying questions. In an attempt to protect the public by not going into details that could help other threat actors, ANU have not released details of how that worked. Possibilities include leveraging the loading of remote content, unpatched email client software or perhaps a zero day vulnerability in either that software or the operating system itself.

The lesson here is that phishing awareness training and other user-level safeguards would not have helped protect the organization against the initial spearphishing attack. That means the importance of a security solution that can recognize and alert on malicious execution regardless of whether the process is trusted or not is the only sure way to deal with the phishing threat.

3. Make the Invisible, Visible | Know Your Network

Understanding what is connected to your network is vital. In the ANU attack, the threat actor sought out and found little-known network devices that had fallen outside of the organization’s security audits.

ANU: “The actor built a shadow ecosystem of compromised ANU machines, tools and network connections to carry out their activities undetected. Some compromised machines provide a foothold into the network. Others, like the so-called attack stations, provided the actor with a base of operations to map the network, identify targets of interest, run tools and compromise other machines.”

With a vast organization spanning multiple sites and multiple sub-networks, the only effective solution is to ensure you can map the network, and fingerprint devices in such a way that you can not only determine what is connected, but also what is unprotected. Many current network mapping solutions have implementation issues such as consuming too much in the way of resources or requiring “noisy” additional mapping devices. Consider a solution that uses your existing security infrastructure without adding on top another layer of burden.

4. Knock, Knock, Who’s There? | Enforce 2FA & Multi-FA

No matter how strong your password, or how frequently you change it, simply relying on only what someone knows without the supporting evidence of something the authorized user possesses is always going to present an opportunity to attackers.

ANU: “Forensic evidence also shows the extensive use of password cracking tools at this stage. The combination of the bespoke code and password cracking is very likely to have been the mechanism for gaining access to the above administrative databases or their host systems.”

With the almost universal use of smartphones among employees these days, linking account access to authentication through an additional device should be standard practise in the modern enterprise. Though neither foolproof nor always convenient, 2FA with time-limited OTPs delivered through mobile Authenticator apps will secure accounts from most simple credential stuffing and other password hijacking attempts. For even stricter control, consider hardware authentication devices such as YubiKey and similar where appropriate.

5. Mind The Traffic | Use Endpoint Firewall Control

Without policies to control what kinds of traffic you want an endpoint to allow and disallow, attackers will have an opportunity to exfiltrate data at will once they have compromised an endpoint.

ANU: “The actor used a variety of methods to extract stolen data or credentials from the ANU network. This was either via email or through other compromised Internet-facing machines.”

Effective endpoint Firewall controls can block unauthorized transfer of data to and from all your endpoints, both on and off the corporate network. In the ANU attack, the threat actor manipulated a commercial tool to query multiple databases, extract records and then exfiltrate the data by sending it to another machine on the network in PDF file format.

Deploying firewall controls allows you to reduce the risk of this kind of data leakage by setting explicit policies that either allow or disallow particular kinds of traffic from the endpoint. Such policies could have prevented the kind of unauthorized data transfers as used in the ANU breach.

6. Pick Off Low-Hanging Vulns | Patch For The Win

Patching is a time-honored security defensive measure, but it’s becoming increasingly important with vulnerabilities like BlueKeep and Eternalblue now on the loose.

ANU: “The actor also gained access (through remote desktop) to a machine in a school which had a publicly routable IP address. Age and permissiveness of the machine and its operating system are the likely reasons the actor compromised this machine.”

Threat actors have the tools to scan for and exploit vulnerabilities in legacy OS like Windows 7 and unpatched Windows 10, Linux and macOS machines. While many departments struggle to replace ageing hardware and software for either operational or budgetary reasons, those departments will remain vulnerable to various threat actors, from cyber criminals motivated by finance to Advanced Persistent Threat groups who may just be hoovering up as much intel as possible while they can.

7. Console Your Clients | Log Devices Remotely

A good security posture requires not just knowing what is happening on your devices but what happened in the past. Logging device activity to a secure remote location is essential for both threat hunting and incident response.

ANU: “The actor exhibited exceptional operational security during the campaign and left very little in the way of forensic evidence. Logs, disk and file wipes were a recurrent feature of the campaign.”

The ANU’s incident response team did a great forensic investigation after-the-fact, but they were hampered by the deletion of logs on vulnerable machines. Modern endpoint detection and response should be backed by a centralized device management console where admins and security teams can access logs from all endpoints regardless of what actions are taken on a device locally.

Similarly, with the correct solution in place such as a tamper-proof agent installed on the local device, the attackers bespoke tools and malware would also have triggered an alert based on their malicious behaviour, regardless of whether they were unknown to signature detection engines that rely on reputation.

Conclusion

The ANU are to be congratulated for making public their detailed Incident Response report. It’s to be hoped that other organizations that suffer breaches take note. Only through this kind of transparency can we share knowledge of how attackers adapt and evade enterprise and organizational security.

ANU weren’t without defenses, and they weren’t without resources. There are many organizations just like them both in the public and private sector. Attackers long ago learned how to defeat the old AV Suite solutions of the past, and that message is something that the ANU report makes clear. A combination of legacy hardware, software and an opaque network structure played into the threat actor’s hands. It is incumbent on us all to learn these lessons and to raise the bar for attackers in light of this report.