You could almost hear the collective sigh of relief across the macOS security research community last week when Craig Federighi, Apple’s Senior VP of Software Engineering, finally spoke up about the problem that many of us have been voicing for several years now: Macs get malware, and Apple are struggling to cope with it.

For some, it’s a tune that can be hard to hear, so good has Apple’s marketing been over the years about the security of its platform. “Apple has built-in tools like XProtect to protect the Mac”, you will hear people say. “Apple has barriers to distribution like codesigning, Gatekeeper and Notarization”; and perhaps the most oft-cited one of all: “The Mac has such small market share it’s not worth the time of financially-motivated malware authors”.

As we’ll see in this post, that last assertion is demonstrably false, and as Apple has now also publicly admitted for the first time, Apple’s layers of security have not prevented malware from becoming a problem for Mac users and indeed for businesses with Mac fleets.

But let’s be clear: our aim here is not to bash Apple. As a hardware, software and services developer and supplier, Apple has many things to do besides malware hunting, detection and protection. Rather, our aim is to illustrate the very real problems facing Apple and Apple users from a growing malware problem that the OS vendor rightly says is “unacceptable”. Help is out there, but Mac users first need to hear what Mr Federighi and the macOS security research community is trying to tell them.

Apple Admit It: Macs Have a Malware Problem

Let’s start with what Apple has now publicly stated. In a wide-ranging testimony ostensibly about iOS security last week, Apple’s Senior VP for Software Engineering, Craig Federighi noted that Macs can be safe:

The kind of malware that incautious users can easily end up with after a few innocent web searches include well-known families such as Adload, Shlayer and SilverSparrow.

Some of the malware that targets macOS users work as ‘pay per install’ delivery platforms that are sold to unscrupulous developers both to inject unwanted advertisements into a user’s browsing experience and to load the user’s Mac with unwanted programs. Such programs typically use high-pressure marketing tactics to lure unwary users into signing up for expensive subscriptions for applications that have very little or no utility. In some cases, these include scareware security programs.

Federighi also noted that gaining access to or control of user data, cameras, and microphones is “incredibly valuable to an attacker”. As many macOS users and developers have noted with frustration over recent iterations of Apple’s operating system, access to these has been increasingly locked down behind so-called ‘transparency, consent and control’ mechanisms that are supposed to keep malware out. These have largely proven ineffective against malware due to multiple known bypasses.

Federighi did not make reference to targeted attacks facing developers and businesses from known and unknown threat actors, but some high-profile incidents such as XcodeSpy and XCSSET have hit the headlines in the last 12 months.

Regarding Apple’s approach to fighting malware, Federighi explained that “Each week, Apple identifies a couple of pieces of malware on its own or with help of third parties” and that the company is engaged in “an endless game of whack-a-mole” in its attempt to fight the “significantly larger malware problem” facing Mac users.

Malware vs macOS – How High Are the Barriers?

Perhaps the most important message for anyone running macOS, particularly businesses with a fleet of Macs, is that the barriers for an attacker to achieve code execution are not as high as they may have been led to believe.

Apple has invested heavily in touting Gatekeeper as the primary barrier to unwanted programs, and backed that up with requirements for code signing and Notarization. We’ve discussed Gatekeeper – really a set of related technologies – in the past. Nothing much has changed with respect to that: it relies on downloaded files being tagged with an extended attribute which is then examined by the OS to see whether it is allowed to execute. There are several points of failure here, all of which in-the-wild malware regularly exploit, and which we’ve described before.

More recent technologies like Notarization are also defeasible by the removal of the same extended attribute: in short, if the attribute doesn’t exist or is removed, the Notarization check won’t come into play.

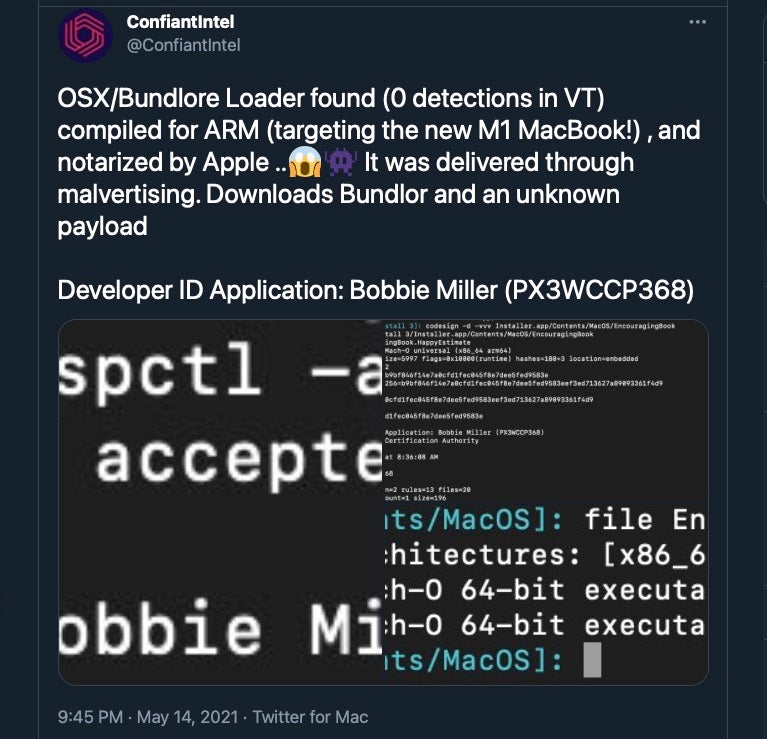

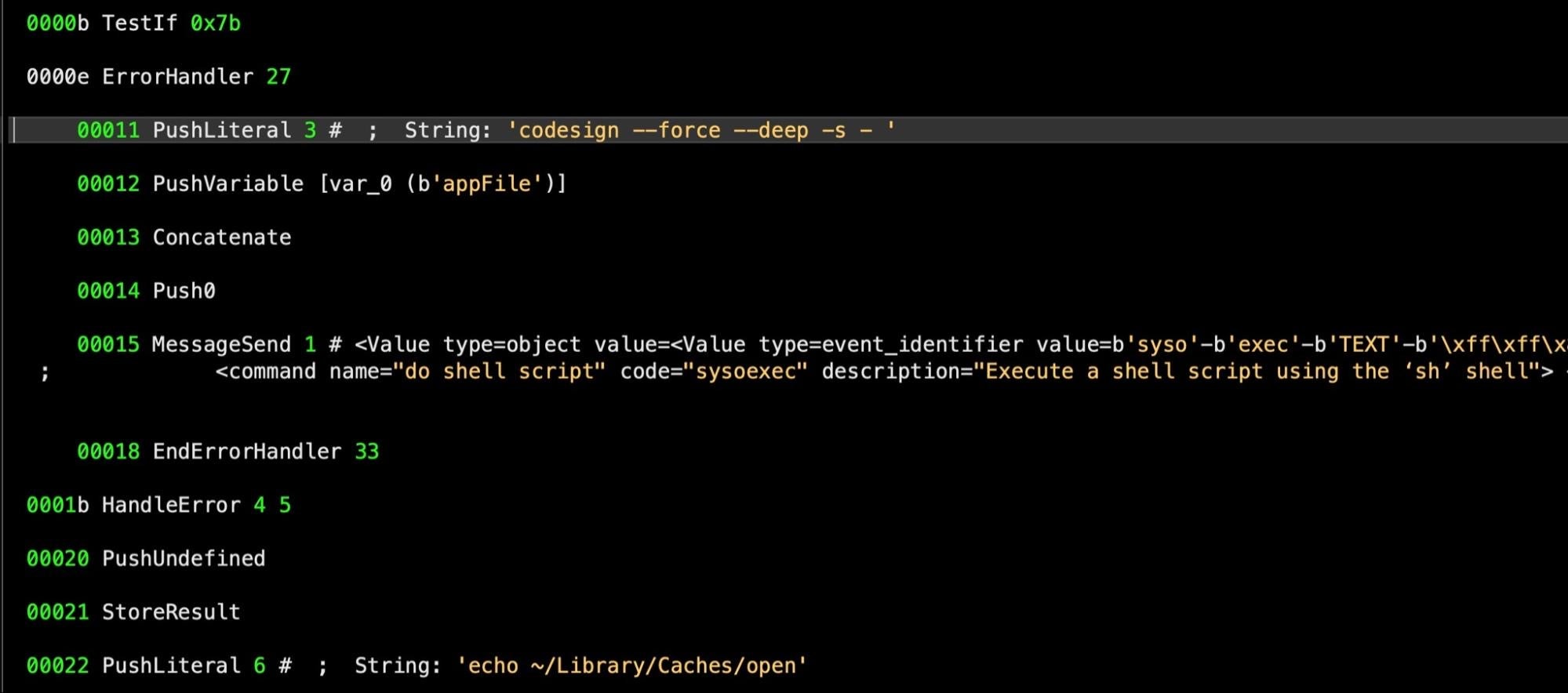

More worryingly still, there have now been numerous cases of malware actually being notarized by Apple. This in part is what Federighi likely meant by saying “it’s an endless game of whack-a-mole”. Malware gets past Apple’s notarization checks, is discovered after the fact, and the certificate is revoked. The malware authors then re-sign the code with a different developer ID and we all get to go again.

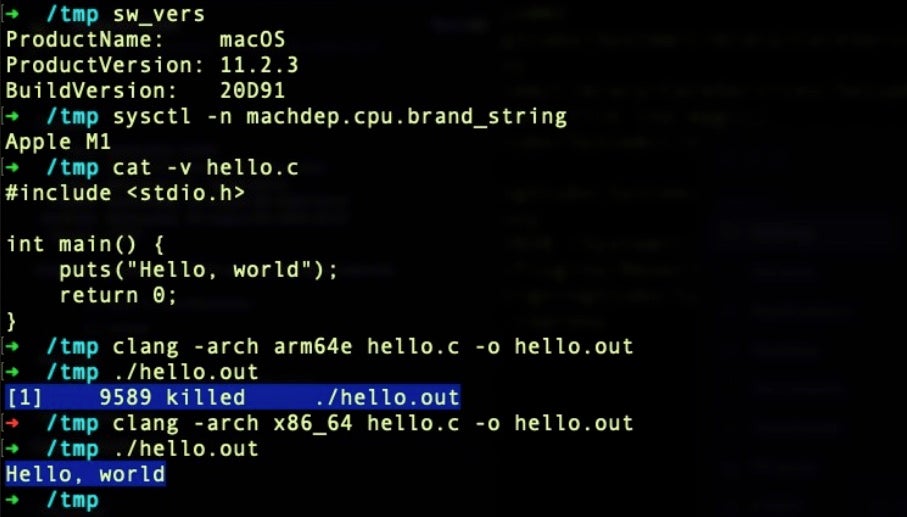

When it comes to code signing and the new M1 Macs, there’s also a couple of gotchas to watch out for: while it’s widely believed that M1 Macs are somehow more secure because code signing requirements are stricter, the fact is M1 Macs can run unsigned code via Rosetta.

Similarly, even when an M1 Mac does check for a code signature, it does not require that the code signature belongs to a known developer. Code signed with an ad hoc signature will run without hindrance, and ad hoc signatures can be created on the fly by other code or by malicious insiders. This technique is currently being used by XCSSET malware for the express purposes of running on M1 Macs.

Testing Known Malware? Beware A False Sense of Security

While we’re on the subject of code signing and certificate checks like Notarization and OCSP, there’s another important caveat to bear in mind when assessing how safe your Macs are from real world macOS malware.

As a security solution vendor, SentinelOne encourages customers to test the efficacy of their security solutions – whether 3rd party or provided by Apple as part of the macOS platform – but depending on what you test, you may get misleading results.

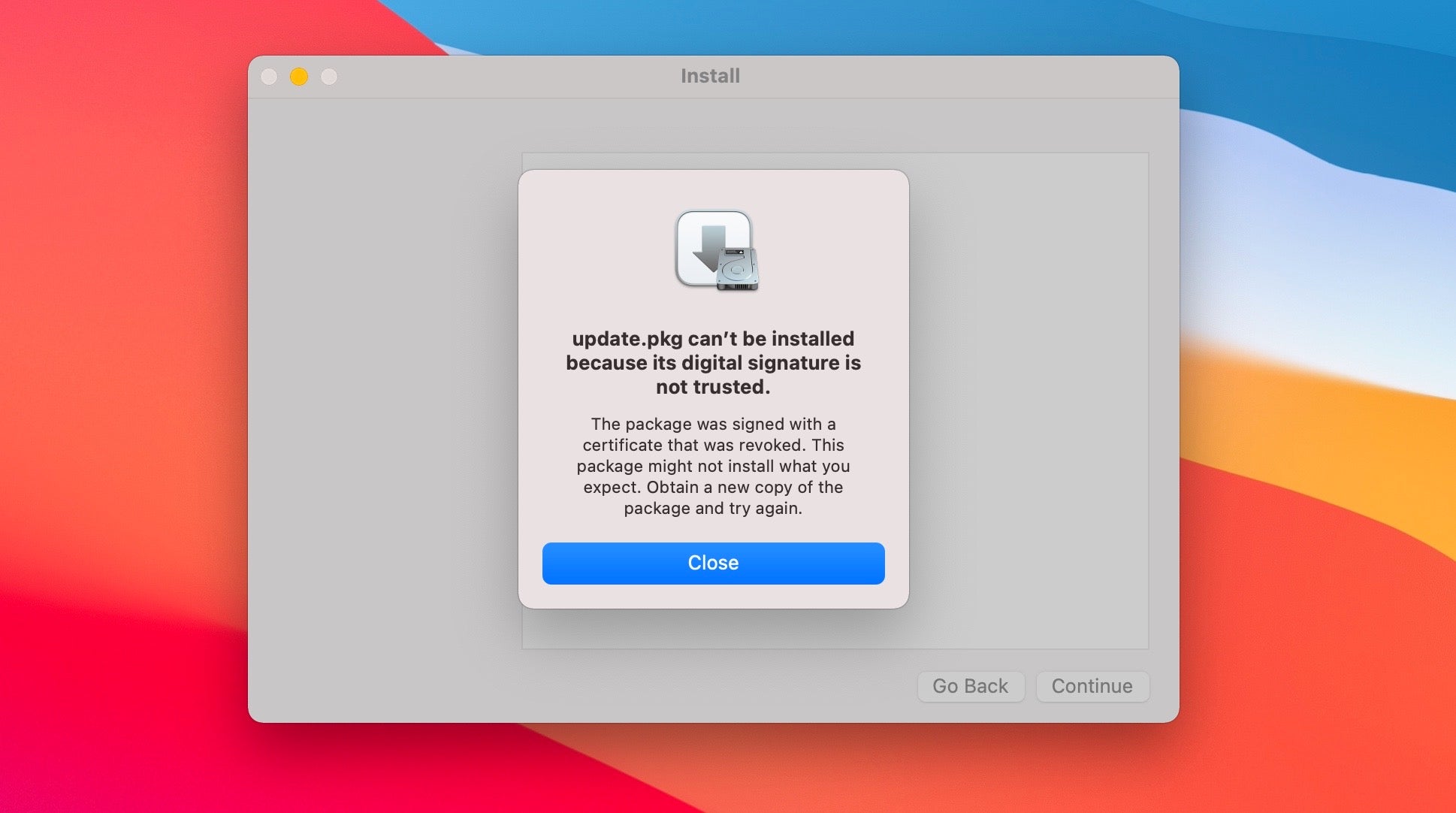

As we noted above, Apple regularly revokes code signing certificates belonging to developers found to distribute malware, and via Notarization, Apple can block specific samples of code that have been notarized by revoking their notarization ticket.

That means if you set about testing a particular known malware family with a sample whose code signature and/or notarization ticket has been revoked by Apple, you will of course see that sample blocked on your test. Importantly, however, you can’t conclude from that test that you’re going to block other samples of the same malware family.

For example, this sample of SilverSparrow malware can be downloaded from the blog of a popular macOS security researcher and will appear to be blocked by the OS if you try to run it:

However, remove the signature or re-sign the malware with a different signature and the same sample will pass those checks (to test that, you would need to use a clean environment from the first test, since once the code is blocked the local device will remember that code is blocked even if you re-sign it or manipulate it in other ways).

Relying on code signatures as a first line of defense is fine, but given the ‘endless game of whack-a-mole’ whereby the same malware just comes back with a different certificate, it’s a barrier that is easily cleared.

What you really want to know is whether you have protection against malware families, not individual samples. Apple provides a built-in technology called XProtect to scan executable files for known malware families. Let’s see how well that works.

Why XProtect Alone Won’t Protect You From Malware

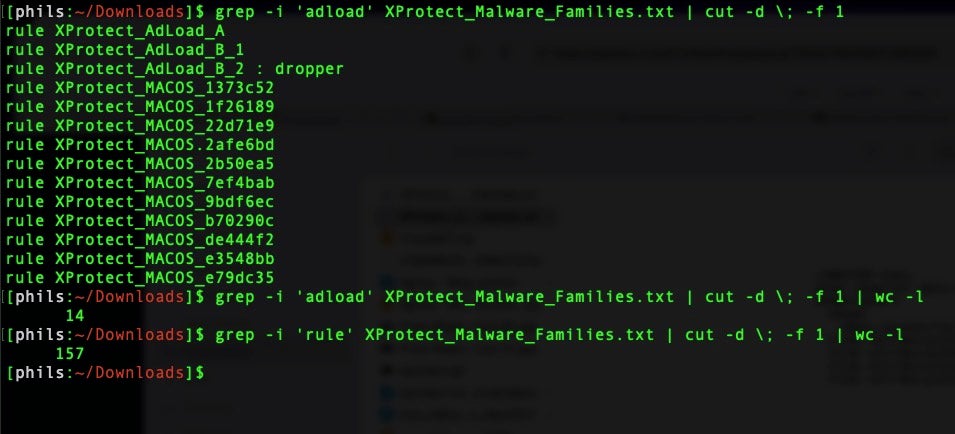

As we noted above, one of the main malware families you can run across in the wild is Adload. This family of malware has been around for some years now, has a number of different variants, and is particularly tricky to remove once it gets a hold in a system. XProtect certainly has some signatures for Adload: 14 of its 157 malware YARA rules are dedicated to Adload variants.

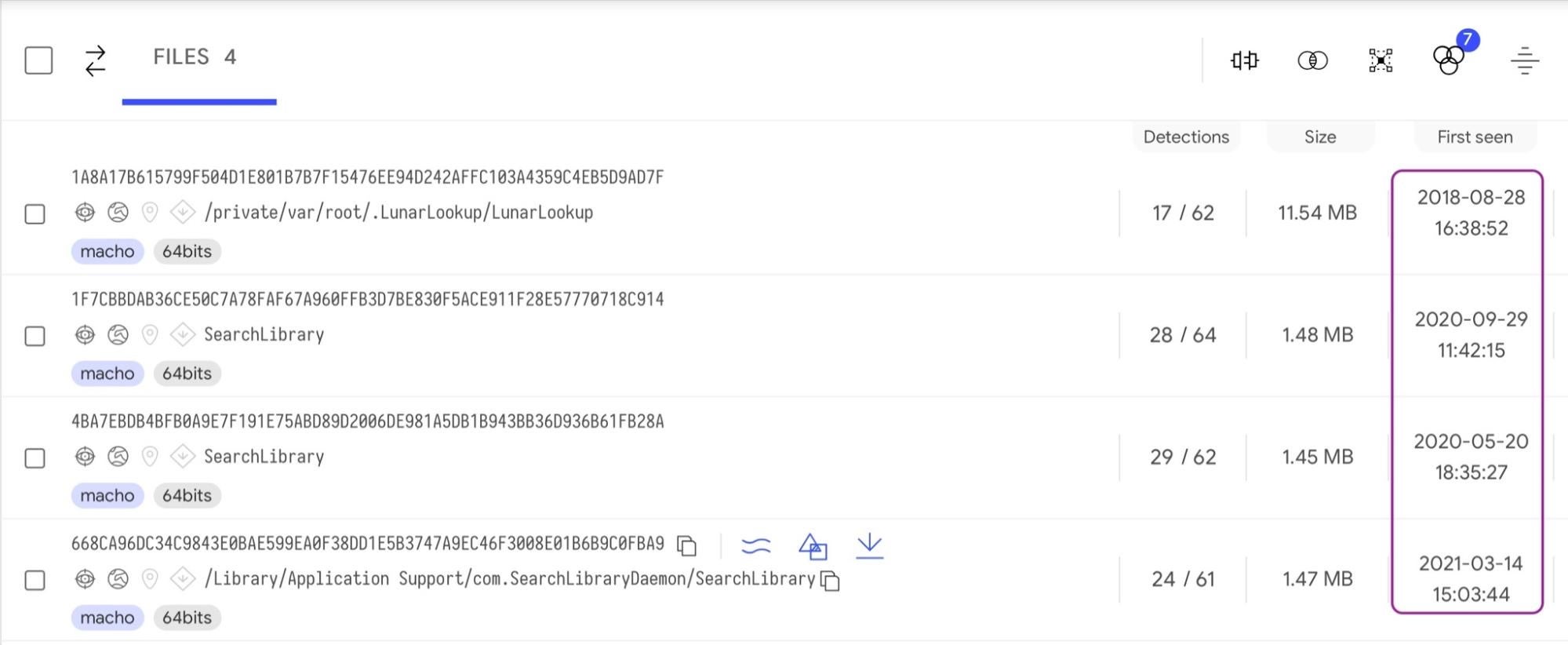

However, it’s trivial to find Adload samples on VirusTotal that are not detected by XProtect, some as old as three years, others a few months.

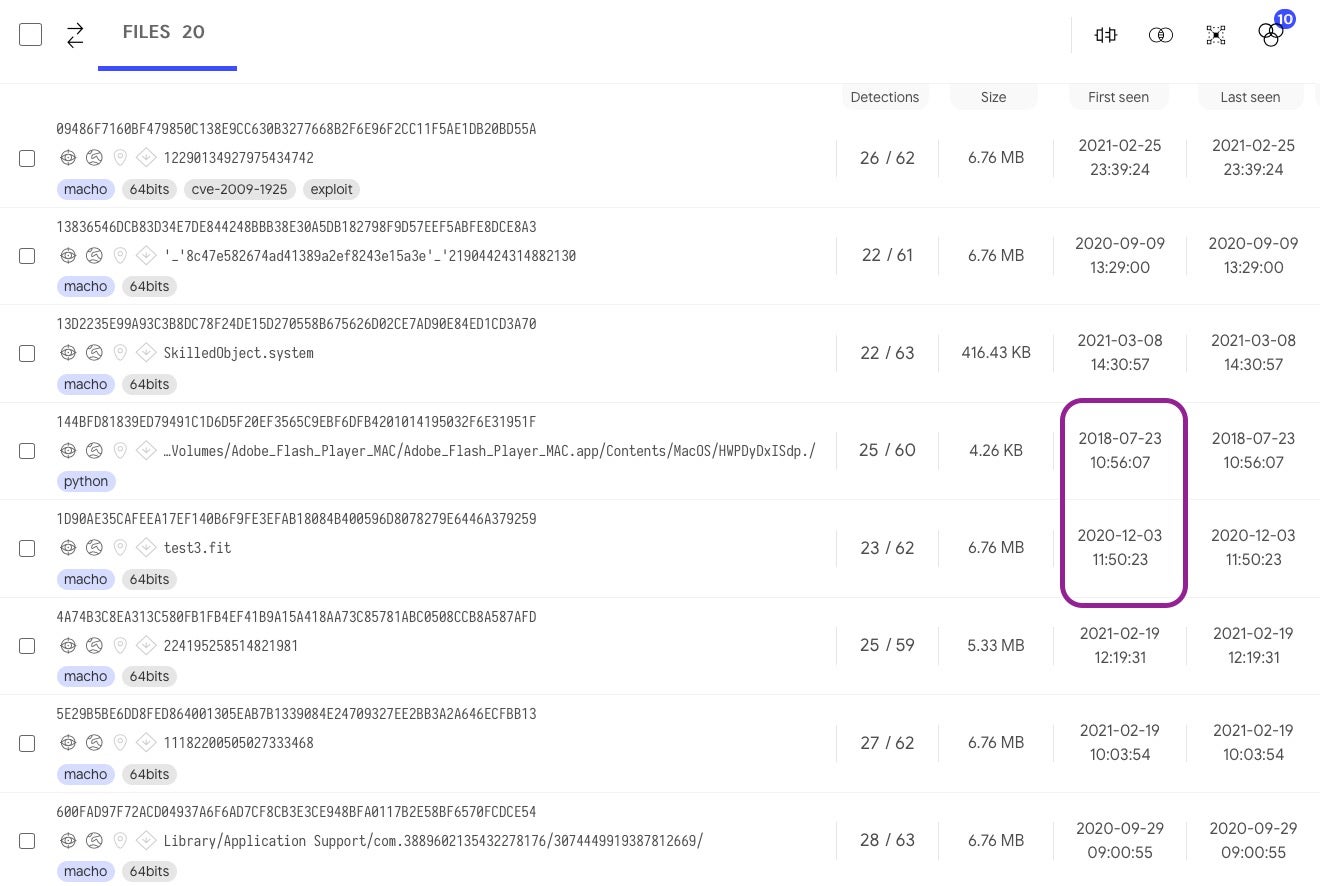

But perhaps that’s not a fair test. It’s easy to pick holes in a security solution for the odd detection miss here or there. Let’s take a selection of known malware families: Bundlore, Shlayer, SilverSparrow, RLoad/Lador, all of which are detected by static AV engines on VirusTotal (the list of 20 hashes as well as those above are provided at the end of this post).

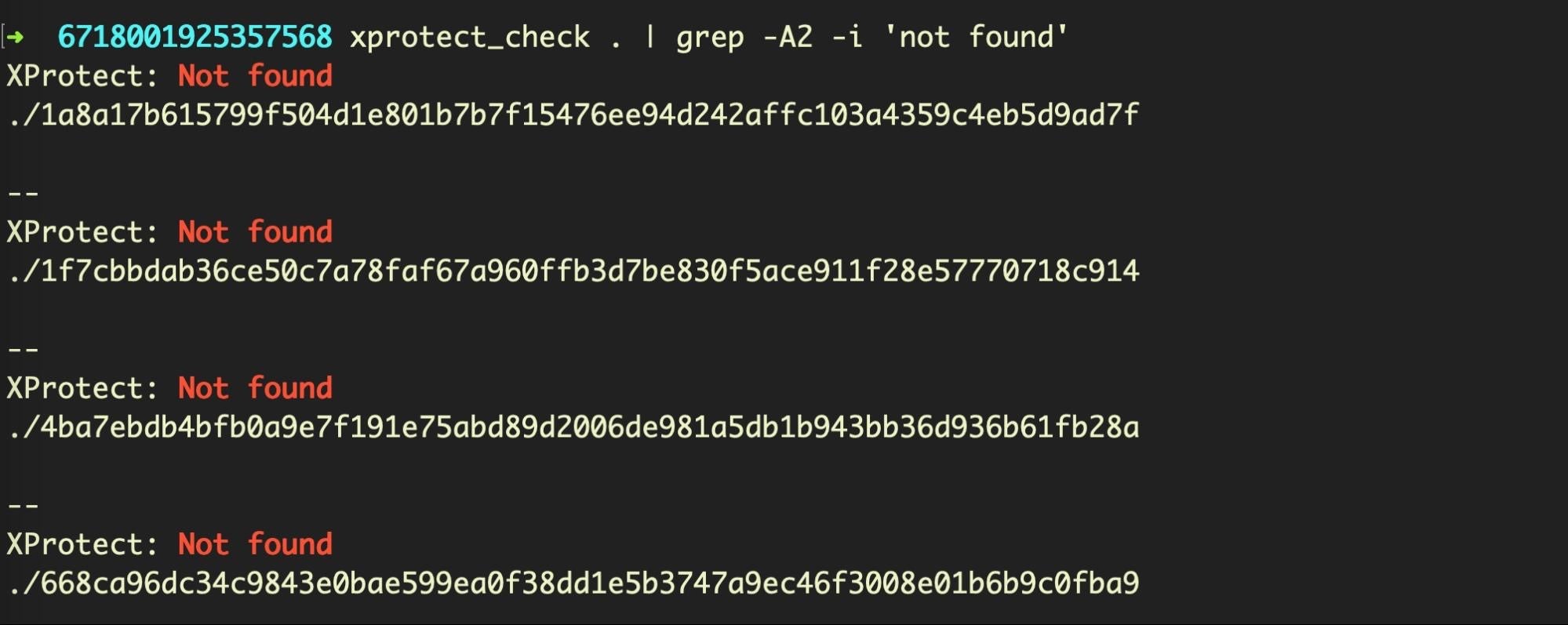

Again, as can be seen from the image of the first eight shown above, the dates these were first detected vary from 2018 to a few months ago. Let’s see how XProtect does with these. If you want to try this at home you will need to install YARA, and then point YARA to the XProtect.yara file.

% mdfind -name XProtect.bundle | grep -i coreservices /Library/Apple/System/Library/CoreServices/XProtect.bundle % yara -w /Library/Apple/System/Library/CoreServices/XProtect.bundle/Resources/XProtect.yara <target dir>

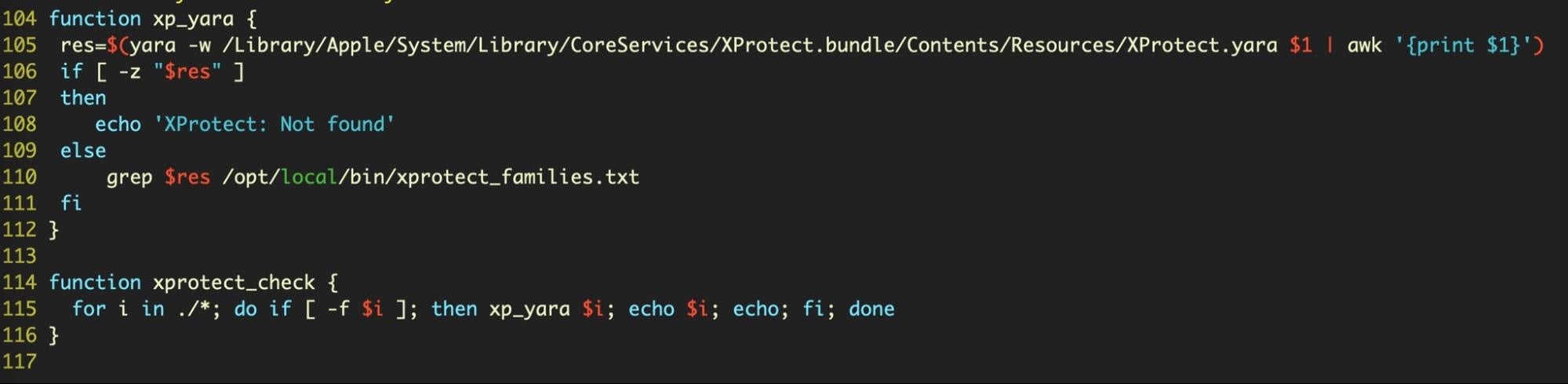

I use a few functions in my shell profile to make this easier (the xprotect_families.txt file is a list of XProtect rule names that can be extracted from this file on SentineLabs github, but it isn’t necessary to run the test).

Unfortunately, XProtect doesn’t have a signature for any of these 20 samples from common, known malware families.

What should we conclude from this? As stated at the outset, we’re not Apple-bashing here: XProtect does do a decent job of blocking the macOS malware that it knows about, particularly since recent versions of the OS ensure files are scanned by XProtect even if they are missing the com.apple.quarantine extended attribute.

The problem is there’s just a lot more malware out there than XProtect knows about. Yes, Apple has another tool, the MRT.app, that can remediate some known malware infections, again if it knows about them, but there are other problems with MRT.app, chief among them the frequency with which it runs (or doesn’t run). We’ve written about MRT.app before at length here and here.

Conclusion

For enterprises running macOS fleets, the macOS malware problem isn’t going to go away on its own or be solved by relying on Apple’s built-in tools, welcome as they are. A solution like SentinelOne brings to the table the missing detection, protection, visibility and control features that macOS lacks. Developed in-house with native support for Apple silicon, kextless and 365+ data retention options, we have a long-term investment in securing Macs. We are Mac users, too, and security is our business.

If you would like to see how SentinelOne can help protect your Mac fleet, contact us for more information or request a free demo.

Samples Used

SilverSparrow

c7dd06b20b64b64d3b155b6b77c2778a08ef6a6c0396d7537af411258e57af1e

The 1st XProtect Test

1a8a17b615799f504d1e801b7b7f15476ee94d242affc103a4359c4eb5d9ad7f

1f7cbbdab36ce50c7a78faf67a960ffb3d7be830f5ace911f28e57770718c914

4ba7ebdb4bfb0a9e7f191e75abd89d2006de981a5db1b943bb36d936b61fb28a

668ca96dc34c9843e0bae599ea0f38dd1e5b3747a9ec46f3008e01b6b9c0fba9

2nd XProtect Test

09486f7160bf479850c138e9cc630b3277668b2f6e96f2cc11f5ae1db20bd55a

13836546dcb83d34e7de844248bbb38e30a5db182798f9d57eef5abfe8dce8a3

13d2235e99a93c3b8dc78f24de15d270558b675626d02ce7ad90e84ed1cd3a70

144bfd81839ed79491c1d6d5f20ef3565c9ebf6dfb4201014195032f6e31951f

1d90ae35cafeea17ef140b6f9fe3efab18084b400596d8078279e6446a379259

4a74b3c8ea313c580fb1fb4ef41b9a15a418aa73c85781abc0508ccb8a587afd

5e29b5be6dd8fed864001305eab7b1339084e24709327ee2bb3a2a646ecfbb13

600fad97f72acd04937a6f6ad7cf8cb3e3ce948bfa0117b2e58bf6570fcdce54

77d04f0bc9b0cd6d1e36b06b347f1e1c283deaef8ae86727ed466fb0042ab5aa

7aa8573af5097567f6655c3ad8d3cd23805db78bd2ee73c25805c00be8a32dae

81241ca5bf3a5e5f31a842385044209f499c5e7109100105da0923752871ba4b

81fcad18c0141a871c27f3574f5ef3bd1e21b747b26226c909158a6f7967d921

9ab8d49663acb378514477abe777c85db0e24383dbd514a6e719d1a5779f2489

c4de173737150eff1b09ec799e1c158b5d1a86b53ed4753624e4bcc8b001e4f3

c8453fe4b79c7b850ed09f9cd51d5d55447ef4d9c0e8d30bcb916b38354e3f44

d8e8b42661387d4ee192fb3cc5d772868973738f090a12ab81d99a40124dbb2d

d965c87f50607467eb9a5c4924572375d0ac5d6a036e558c30f11797d5c59548

dbbbe53d7a7d62896a1383cc2aa62b7a82d93c0a8c94cf0caf4611cc487e9a65

ea7e53c7e5017f9f41306361f79167da960e23dd26b488cae1b62d94c2b3b474

ec2f66f8e5dd7b24b1d8bde1e0f32a4d81aa908ff514b205afd3a170a3036d55