The Good

A transatlantic cybercrime operation was busted last week by Spanish Guardia Civil. Sixteen suspects in eight different locations throughout Spain were arrested on charges of laundering funds stolen through banking trojans made by Brazilian cybercrime groups. These groups developed and rented the banking trojans known as Mekotio and Grandoreiro, very capable pieces of malware targeting Windows computers through phishing emails. Post-infection, they remain hidden until the user logs into their banking accounts, silently harvesting credentials.

The police seized €276,470 in cash and, after forensic examination of the suspects’ computers, found an additional €3.5 million stashed away which had not yet been cashed out.

Back in North America, the U.S. government is stepping up its efforts to battle ransomware. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and CISA have launched a website that aims to provide comprehensive information regarding ransomware attacks.

The site, stopransomware, includes guidance and resources, general information, tips, a Ransomware Readiness Assessment tool and a dedicated page for reporting ransomware incidents to the authorities.

The Bad

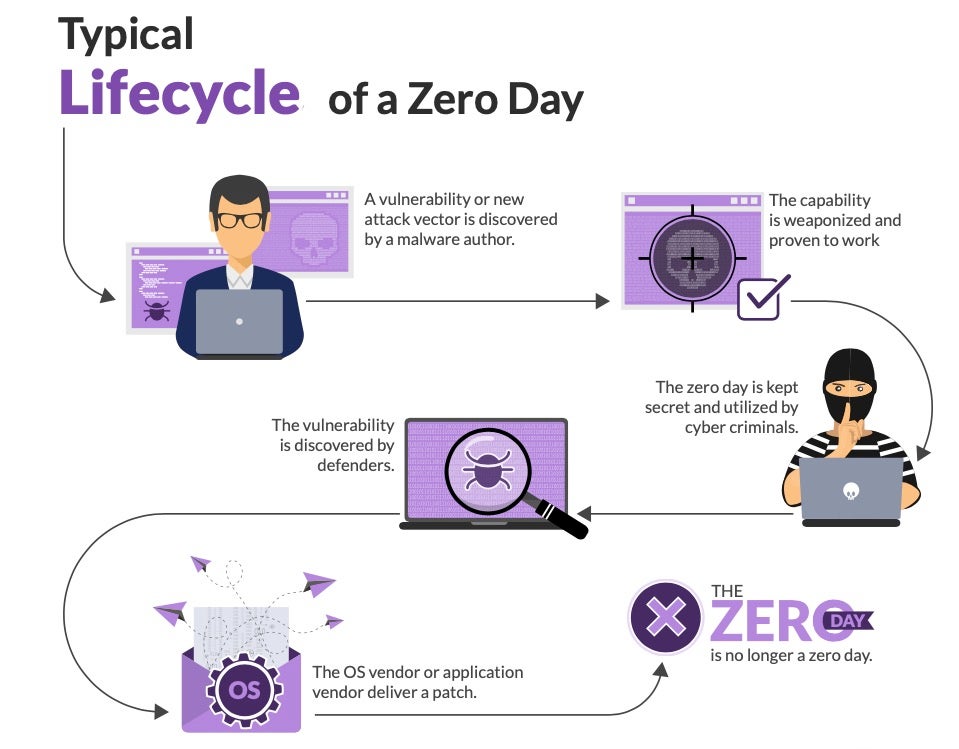

Software vulnerabilities are prime targets for attackers, who seek to identify and weaponize zero-day vulnerabilities. But this is a very expensive process that requires extremely skilled researchers. This is why traditionally it was only undertaken by well-funded, advanced nation-states. Now, however, commercial entities are doing their own research and selling weaponized zero-day end-products to whomever can afford them. While this has been known for some time, the general perception was that these enterprises focused on mobile exploits and to a lesser degree (and capability) on standard operating systems.

According to Google’s Threat Analysis Group (TAG) and Project Zero, four new zero-days were recently used as part of three targeted campaigns. These campaigns exploited previously unknown flaws in Google Chrome, Internet Explorer, and WebKit, the browser engine used by Apple’s Safari (CVE-2021-21166 and CVE-2021-30551 in Chrome; CVE-2021-33742 and CVE-2021-1879 for IE and Webkit, respectively).

Google says that three of these exploits were developed by a commercial surveillance company which then sold the vulnerabilities to two different government-backed actors. “Based on our analysis, we assess that the Chrome and Internet Explorer exploits described here were developed and sold by the same vendor providing surveillance capabilities to customers around the world”.

The Ugly

What does the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) have to do with cyber espionage? According to a recent study, Iranian attackers presented themselves as research fellows working at SOAS and contacted journalists covering the Middle East, Think Tank experts and senior professors.

The threat actors invited their unsuspecting victims to participate in an online conference called “US Security Challenges in the Middle East”. They then directed these contacts to a registration page, which was actually a compromised website belonging to SOAS, in order to steal Google, Microsoft and other single sign-on or email log-in credentials.

Based on TTPs and target selection, the activity has been attributed to TA453 (aka APT35, Phosphorus, and Magic Hound), an attack group affiliated with Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). One of the scholars who had his identity “borrowed”, told reporters “Of course it’s stressful, but on the upside I had conversations with a lot of interesting people that I would probably not have had interaction with otherwise. I’m taking it as a lived case study”. That’s the spirit!