Both researchers and safety-conscious computer users rely on online anti-malware sandbox service VirusTotal in order to keep up with the latest threats, and to check whether suspicious samples they discover in the wild are already known offenders. One of the great features of this tool is that anyone can upload anything and immediately check to see if it’s a recognized threat.

Surprisingly, it’s not unknown even for threat actors themselves to make use of services like VirusTotal by uploading their own malware to see whether it is detected. While it may seem counterintuitive for malware developers to give advance warning of their products to anti-malware services, it is one way for such developers to test if their creations will avoid existing detection algorithms, as well as find out how their software’s anti-detection methods function in real-life. In a study published in 2015, it was found that over 1500 malware samples were pre-released on VirusTotal and other online virtual sandboxes before becoming part of public malware campaigns.

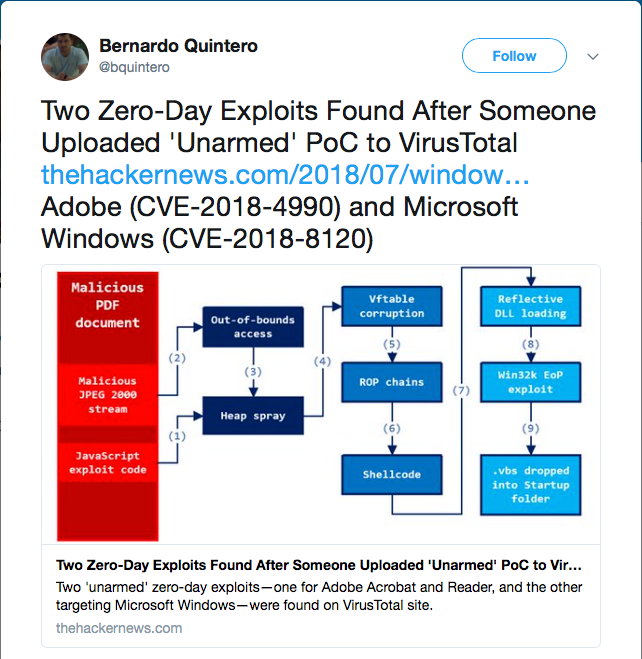

With that in mind, researchers are keen to search for and “retrohunt” undetected or poorly detected submissions occurring on these sites, conscious of the fact that they may well be able to update their own detection mechanisms to catch emerging malware before it’s ever seen in the wild. This was dramatically illustrated in March of this year, when two zero-day vulnerabilities affecting Adobe and Microsoft were discovered and pre-emptively patched as a result of a ‘proof-of-concept’ (PoC) being uploaded to VirusTotal.

It is, truly, a game of cat-and-mouse being played out on public services.

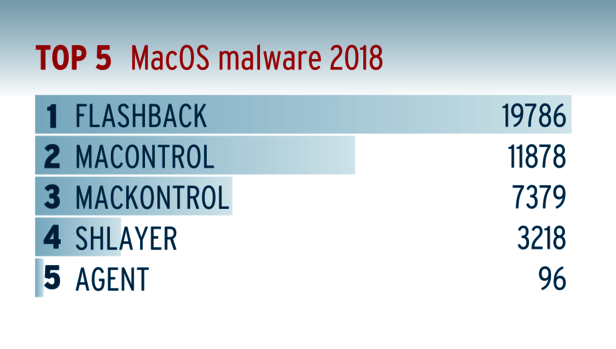

This game took an unusual turn recently when a SentinelOne researcher noticed something peculiar about the figures being cited for macOS malware infections in the first half of 2018. Independent research institute AV-Test, whose stated mission is to compare and test major AV solutions, noted that FlashBack and MaControl (aka ‘MacKontrol’, ‘MacControl’) were by far and away the most prevalent threats on the macOS platform so far this year.

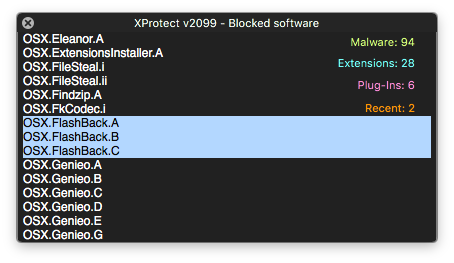

Of course, it’s no surprise that malware is on the increase across macOS. What is a surprise is that FlashBack and MaControl should be so prevalent. FlashBack and MaControl hit the headlines in 2012, and even then were not the first of their variants to be found in the wild. Even for those that are still sailing perilously close to the malware winds by not hardening their kit with a comprehensive anti-malware solution like SentinelOne, those numbers are rather eye-opening. That’s not just because we’re talking about six-year old threats. It’s also because FlashBack and MaControl are recognized by Apple’s own basic anti-malware tools – Gatekeeper, XProtect and MRT – which will block, recognize and remove a number of these variants.

While it may be the case that Apple’s detections are often not as up-to-date as those of dedicated security vendors like SentinelOne, the fact is most reputable macOS anti-malware products are well aware of all currently-known FlashBack and MaControl variants. Moreover, in 2014, Apple bought up all the C&C domains known to be associated with the FlashBack bot, and the Java vulnerabilities associated with the last known variant were closed in late 2013. To all intents and purposes, FlashBack has never been active since. How, then, can it be possible that FlashBack and MaControl are still being seen in the wild in such vast numbers?

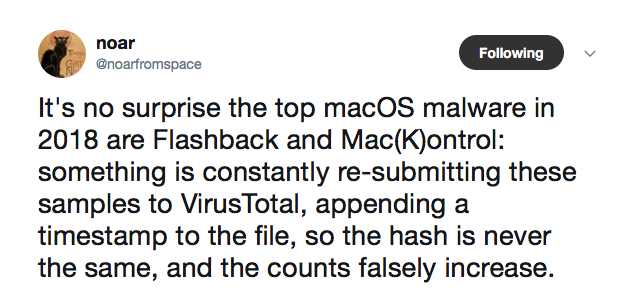

One clue was found by the SentinelOne researcher after analysing samples on VirusTotal:

Further research by SentinelOne’s macOS team found that identical samples of both FlashBack and MaControl were being submitted with incremental timestamps multiple times in the same day.

Making a Hash of it

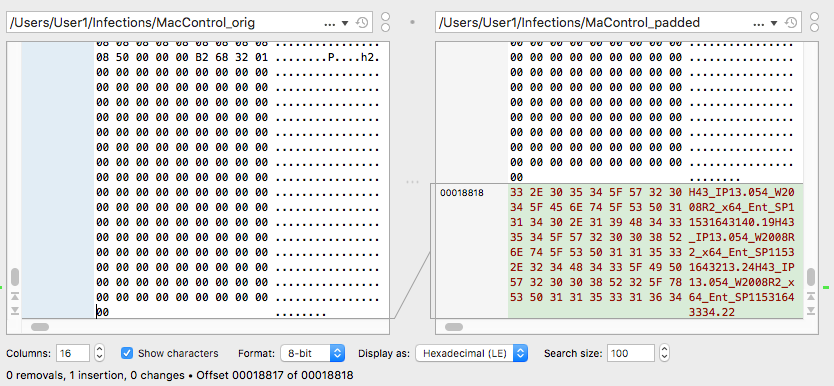

To see how this might affect detection, let’s compare the original MaControl sample with a recently uploaded one. Conducting a binary diff on the two files shows that they are identical save for an insertion at the end of the file:

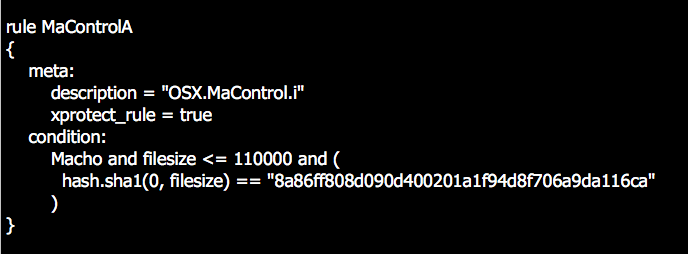

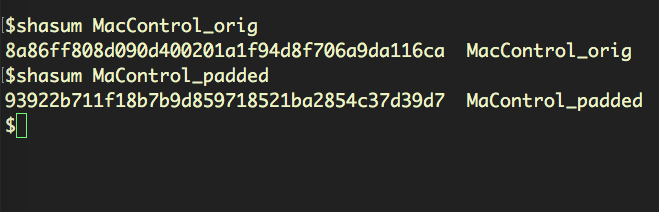

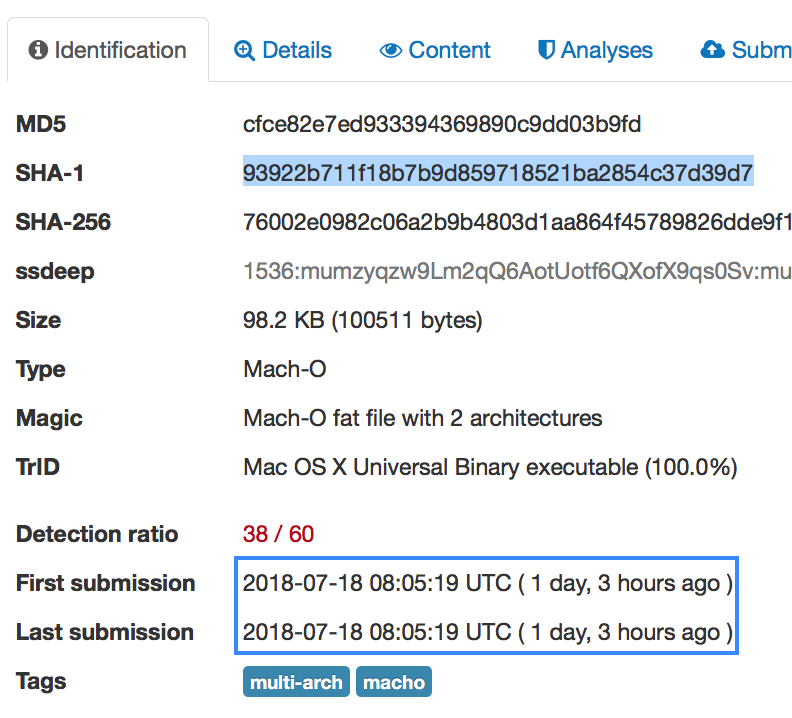

Worryingly for unprotected Mac users, Apple’s built-in security tools won’t detect the “padded” sample. Apple’s identification procedure relies on a Yara rule that matches against the file’s Sha1 hash:

However, the padding changes the file’s Sha1 from 8a86ff808d090d400201a1f94d8f706a9da116ca, recognised by XProtect, to 93922b711f18b7b9d859718521ba2854c37d39d7, which won’t match the search rule and will allow the file to go unnoticed by Apple’s security protections.

Interestingly, we can take the padded version, delete the appended string and turn it back into a copy of the original, which XProtect will now notice. This proves that there is no other difference between the original sample from 2012 and the one recently uploaded to VirusTotal, other than the padding at the end of the binary.

Automated Variants

At this point, one might assume that malware authors must be responsible for creating these minor variants so as to avoid detection, but it turns out that the story is a little more complicated than that. We can start to see why when we examine the nature of the padding at the end of the file.

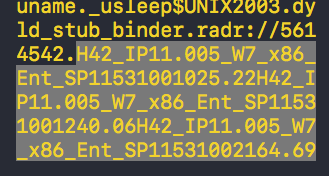

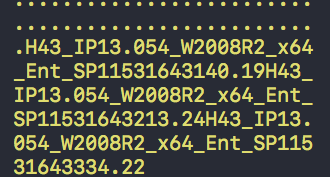

Here’s the padding on the end of a FlashBack variant, followed by the padding on the end of a MaControl variant:

They look surprisingly similar, having the form of multiple “H” strings:

FlashBack sample

H42_IP11.005_W7_x86_Ent_SP11531001025.22

H42_IP11.005_W7_x86_Ent_SP11531001240.06

H42_IP11.005_W7_x86_Ent_SP11531002164.69

MaControl sample

H43_IP13.054_W2008R2_x64_Ent_SP11531643140.19

H43_IP13.054_W2008R2_x64_Ent_SP11531643213.24

H43_IP13.054_W2008R2_x64_Ent_SP11531643334.22

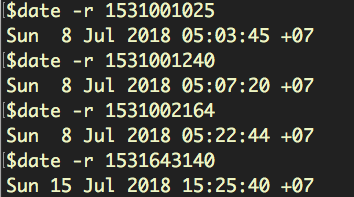

The body of the strings seem to indicate different versions of Windows and the end of the strings, as discovered by the SentinelOne researcher mentioned above, turn out to contain Unix timestamps:

These are, of course, unrelated to the actual timestamp of the file’s submission to VirusTotal:

However, removing one timestamp at a time, re-calculating the hash and searching for the hash on VirusTotal produces, in most cases, a hit for a recently submitted sample.

Further investigation revealed that over 10000 unique variants of FlashBack containing “H” strings had been added to VirusTotal. As for MaControl, in some cases, a unix timestring was appended to the file’s __LINKEDIT segment either as well as or instead of the “H” string to create yet further variants of the same file. Our research showed that in July alone, 1000+ MaControl variants had been submitted to VirusTotal exactly one time only.

It is not clear who has been uploading these variants, but given the sheer volume and the common form of the “H” string and unix timestrings, it’s reasonably likely the source is both automated and singular. The samples show the embedded timestrings represent dates that are often incredibly close together:

Thu 12 Jul 2018 08:51:05

Thu 12 Jul 2018 08:52:37

Thu 11 Jul 2018 23:56:07

Thu 12 Jul 2018 00:00:05

In the case of this sample, the actual upload time was 3 days later.

Moreover, as far as we are aware, there is no common authorship or distribution channel shared by FlashBack and MaControl. We also note that, despite the fact that Apple’s built-in detection is easily fooled by a change of hash, these variants are widely detected by engines on VirusTotal. SentinelOne, of course, which doesn’t rely simply on either hash or signature based detections, recognises these variants regardless of changes to the binary. For these reasons, it seems unlikely that these samples are being mutated and submitted in order to defeat known security software.

Finally, we were able to ascertain from the metadata available on VirusTotal that the uploader was uploading via a programmatic interface using an API key.

Wrapping Up

Whether these submissions are due to bad actors attempting, for reasons as yet unknown, to inflate the extent of FlashBack and MaControl, or whether they are a result of “friendly fire” – an automated script used, perhaps, by a security vendor that has, unnoticed, gone out of control – remains to be seen.

What is clear, though, is that as security researchers rely on analyses of submissions to services such as VirusTotal, there is a real possibility that malware hunters could jump to the wrong conclusions as a result of such submissions. Not only is it possible for research to drown in irrelevant noise when submissions are inflated like this, it could lead to a misunderstanding of the nature of the current threatscape. Are FlashBack and MaControl really among the top 5 threats macOS users are facing at the moment? Or are they yesterday’s threats being dug up and, literally, rehashed? And if the latter, then what really is the most prevalent malware on macOS in 2018?

Our findings were reported to VirusTotal before publication. We’ll keep SentinelOne readers updated as and when more information comes to light.

Read More About MacOS Security

Calisto Detected installing Backdoor on macOS

The Weakest Link: When Admins Get Phished | MacOS “OSX.Dummy” Malware

OSX.CpuMeaner: New Cryptocurrency Mining Trojan Targets MacOS