Spotted: An adware installer tries its best to avoid detection but leaves behind more clues than intended. Scroll down to find out more!

Trojan installers delivering adware and unwanted applications (PUPs) have been the most prevalent security nuisance on the macOS platform in recent years. To date, these have engaged in little more than low-level scraping of user data and browsing habits, but their potential to be far more threatening is only awaiting the right monetary incentive. A recent report on what appeared to be a run-of-the-mill adware infection set us on the trail of OSX.FairyTale, an adware variant first identified in early 2018 by Malwarebytes researcher Thomas Reed. FairyTale uses a lot of heavy obfuscation and anti-reversing technology, not unusual for malware, but overkill for simple adware. We decided to take a closer look.

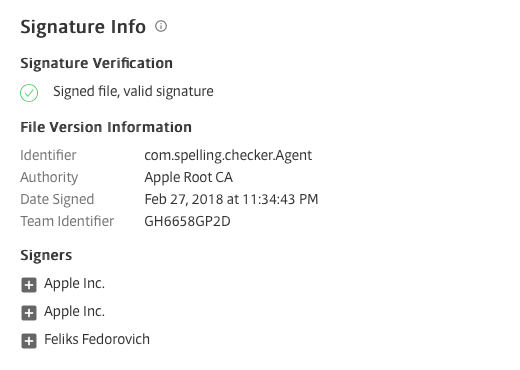

Our sample came in the guise of a trojan installer called SpellingChecker.app that was uploaded to VirusTotal in late August. The application bundle is signed with a valid Apple Developer ID:

However, that has since been revoked by Apple:

Sentinel:$ spctl --verbose=4 --assess --type execute SpellingChecker.app

SpellingChecker.app: CSSMERR_TP_CERT_REVOKED

Static analysis of the installer binary reveals two things of immediate note: an attempt to escalate privileges with AppleScript, and a lot of base64 encoded strings.

do shell script "%@" with administrator privileges

H0VDQh9SWV4fSFFEREI=

HUJT

H0VDQh9SWV4fX0BVXg==

We knew things were going to get interesting when our first attempt to decode the base64 only spewed out gibberish:

Sentinel:$ echo H0VDQh9SWV4fSFFEREI= | base64 -D; echo

ECBRY^HQDDB

Sentinel:$

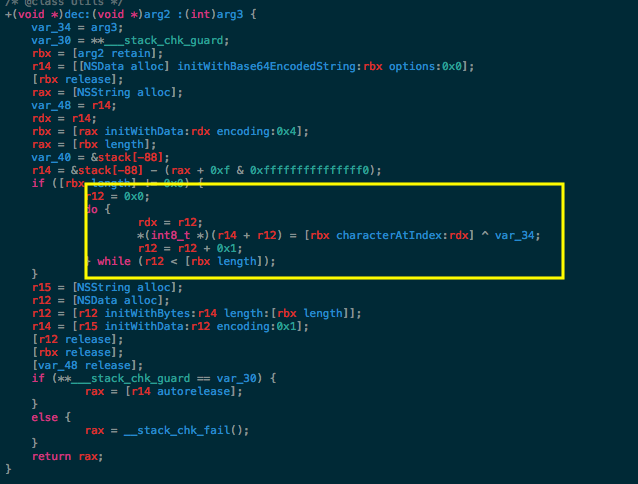

A quick trip to Hopper showed us the pseudo-code for the decryption method:

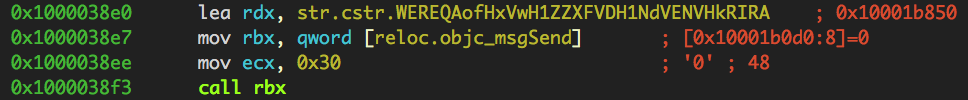

A fairly-straightforward XOR, which we re-implemented in Objective-C. Looking at the arguments passed into the method, the base64 was XOR’d with 0x30 (48 in decimal):

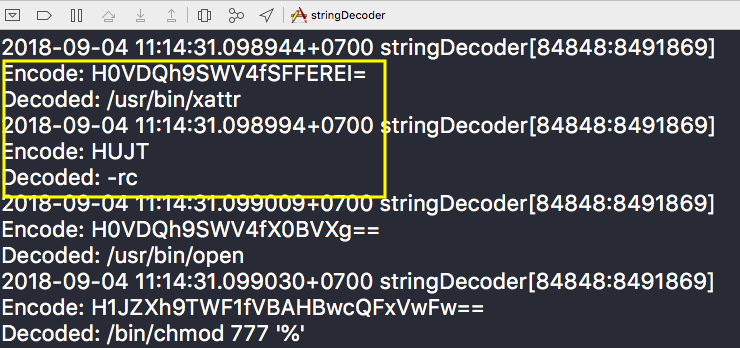

Using our decoder, we were now able to see what the installer was up to: an XProtect bypass:

Using xattr to remove Apple’s quarantine bit is a common technique used by researchers. It makes it possible to run and examine malware on a Mac even after it has been blocked by Apple. Clearly, this trick hasn’t gone unnoticed among malware authors, either.

FairyTale’s installer had another surprise for us, too. For both safety and convenience, malware researchers make use of virtual machines to analyse samples, but FairyTale’s authors didn’t want anyone looking at their code in a virtual machine:

Decoded: ioreg -l | grep -e 'VirtualBox' -e 'Oracle' -e 'VMware' -e 'Parallels' | wc -l

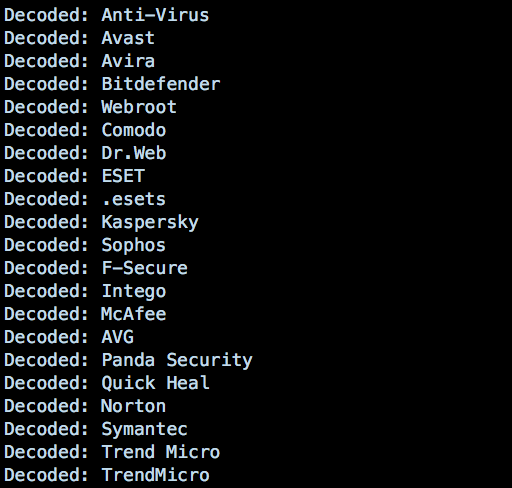

And they didn’t want to get caught by Legacy AntiVirus software either, as this list of de-obfuscated base64 strings makes clear:

On execution, the Installer takes a trip to Temp folder where it drops the following compressed file:

/tmp/ot3497.zip

After unpacking the zip file, FairyTale then writes and loads a persistence agent and its executable to the following paths:

~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.sysd.launchserviced.plist

~/Library/Application Support/com.sysd.launchserviced/launchserviced

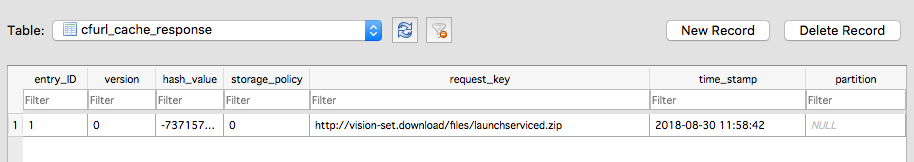

The installer uses the xattr to both remove the quarantine bit and the kMDItemWhereFroms bit, which is used by Spotlight and MDQuery to keep track of where a file has come from. Typically, for downloads, that will be the URL from which the file was sourced. Fortunately, macOS has other ways of spilling secrets; namely, in this case, in ~/Library/Caches/com.spelling.checker.Agent sql database:

From this, we can see that the installer grabbed the launchserviced.zip from

http://vision-set.download/files/launchserviced.zip

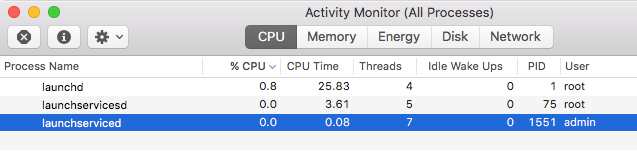

Stealth was undoubtedly on the author’s mind. The name of the executable, launchserviced, is just one letter different from the name of a real Apple process that runs on every user’s Mac. The highlighted item below is OSX.FairyTale trying to blend in with legitimate Apple processes:

Clearly, FairyTale aims to go unnoticed or to be taken for something legitimate.

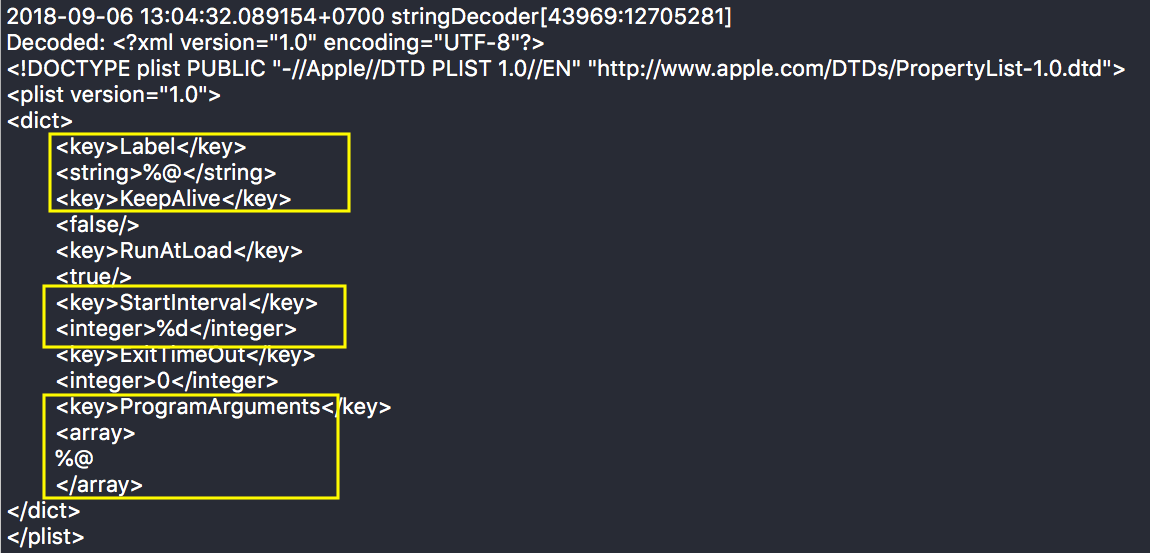

Among the installer’s obfuscated base64 is the template for a property list file:

Notice that it uses placeholders for some of the keys: label – the name that is typically used for the property list’s filename and also the name it gives to launchd when it’s loaded; StartInterval – which tells launchd how often to run the job; and ProgramArguments – an array of commands to pass to the job when it runs.

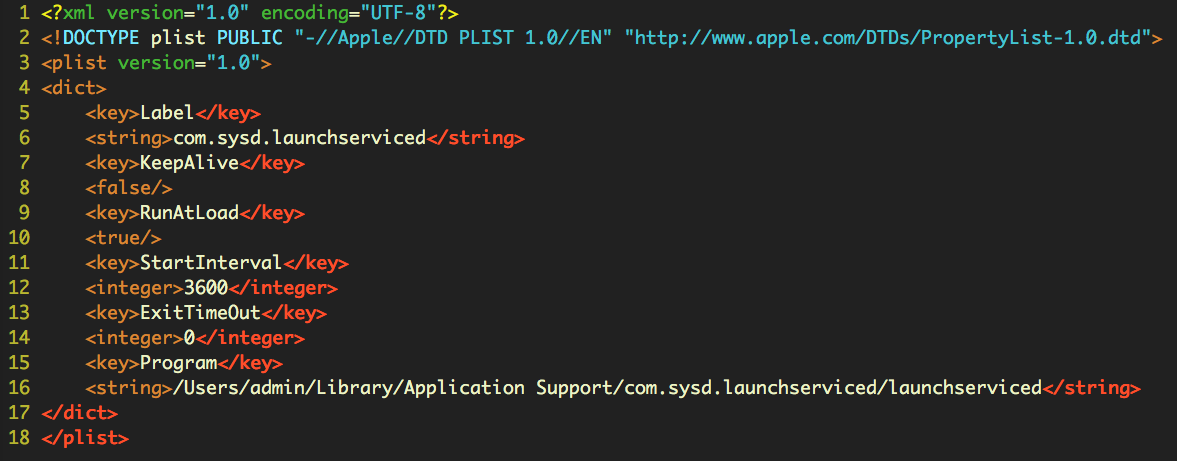

Again, the intent is clear: this isn’t a one-off package, but a re-usable installer for any payload the author chooses. Here’s the actual property list dropped for Spelling.Checker, with a start interval of 3600 seconds, i.e., every hour:

The dropped version used the Program key rather than ProgramArguments key, which tells us that no commands are passed to the executable on launch in this case. Although the property list structure is correct, it’s an unnecessary change, as the same effect is achieved by simply passing in the program path as the first argument to the ProgramArguments key.

It seems the coder is a careful programmer who pays attention to details. Alas, like all villains in a FairyTale, it’s the bad guys’ own actions that lead to their downfall, and this story is no different when we look at the launchserviced binary.

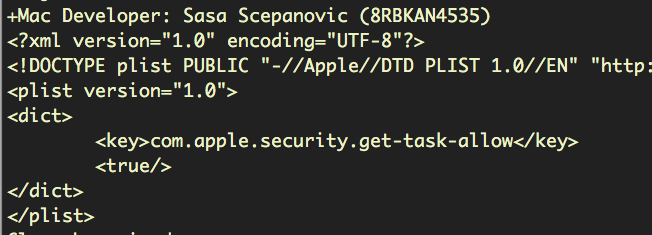

After all the effort put into avoiding detection and reverse engineering, the author of launchserviced made an error, and appears to have accidentally allowed debug entitlements in the binary:

Although not currently enforced by Apple, the com.apple.security.get-task-allow entitlement is intended to allow a debugger to attach to a sandboxed app when it’s running. This is necessary during development to allow Xcode or the low-level debugger (lldb) to launch and inspect the running code. However, the entitlement is stripped automatically when code is exported for distribution through Xcode’s Organizer. The presence of it here suggests that the developer copied the target from the project after building it, or perhaps exported the binary using ‘debug’ rather than ‘release’ settings.

We also see this binary is signed with a different developer ID than the revoked one used for the installer. Although it’s not possible to tell whether this signature is revoked, we have reported it to Apple and assume they are investigating.

When executed, the launchserviced appears to have relatively benign behaviour. If Safari is open, it is redirected through several sites and finally lands on online-empire.co:

Other addresses loaded include rdtrck2.com and bizprofits.go2cloud.org,

rdtrck2.com, bizprofits.go2cloud.org and tracklik.com.

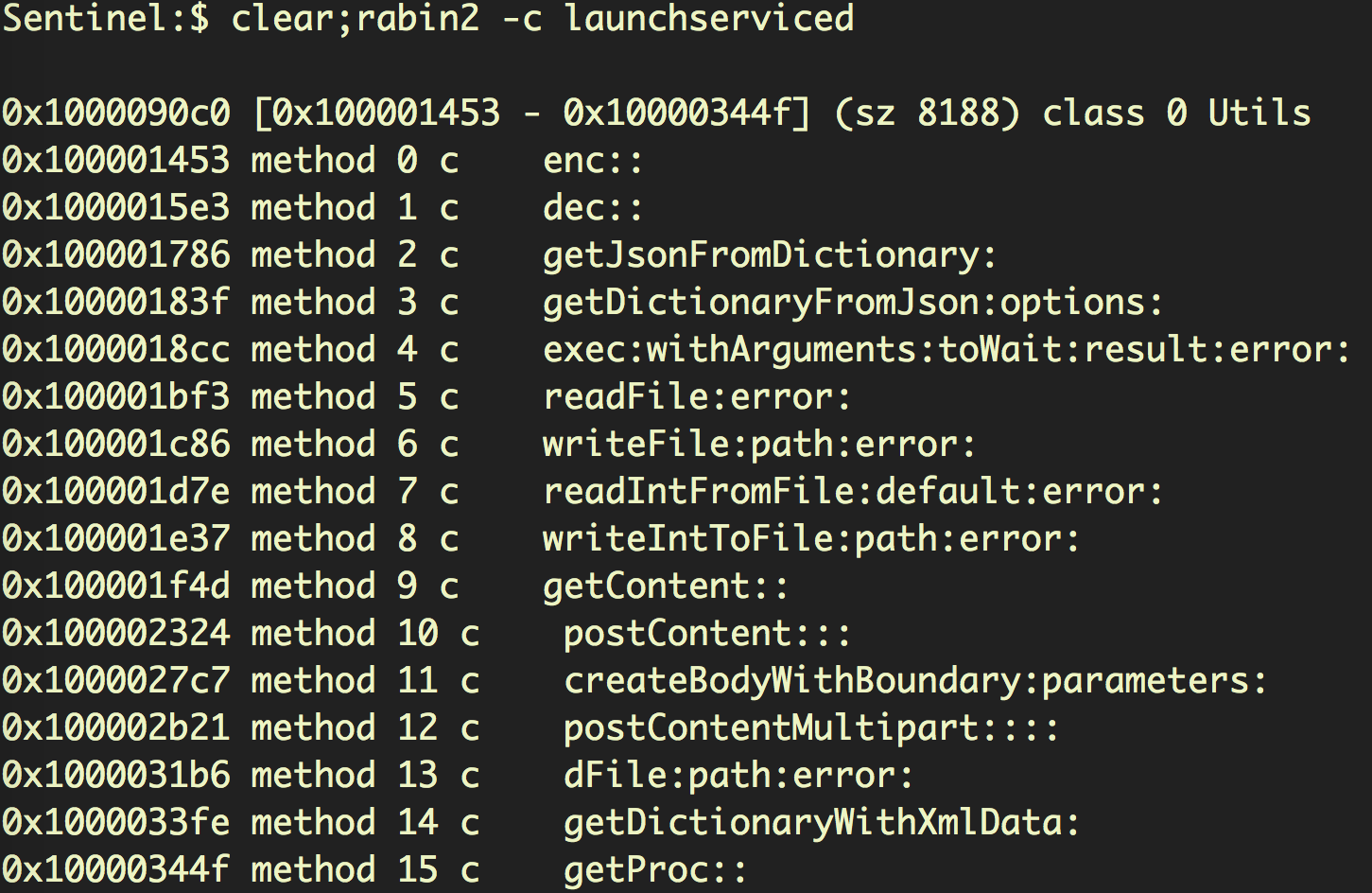

Further static analysis of the code reveals methods that we’d expect to see in browser redirection:

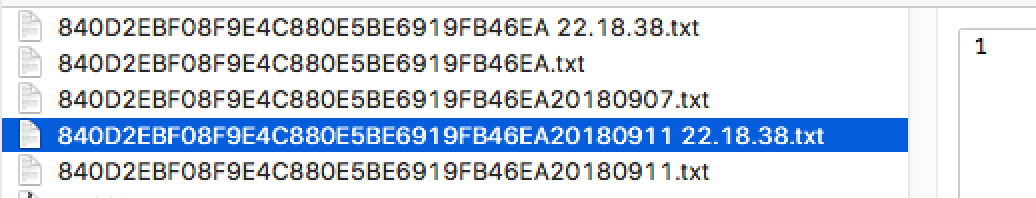

Two data files are written to the executable’s parent folder with a hard-coded file name prefix 840D2EBF08F9E4C880E5BE6919FB46EA. The files contain a single byte, which in our tests was either ‘1’ or ‘2’.

A Happy Ending?

OSX.FairyTale is an interesting adware variant not because of what it does, but because of the techniques used to prevent detection and analysis. Considerable effort has been expended in hardening the installer code to prevent reversal, and launchserviced was clearly named for stealth. Given the rather unadventurous behaviour of the launchserviced code, we can only assume that these efforts were either a proof-of-concept or part of a larger project still in development.

The developer signatures and code are now on the radar, but like many a real-life FairyTale, we won’t be surprised to see this one get retold and adapted for other purposes in the future.