With Mojave’s security hardening, any local or remote user can bypass Apple’s new Full Disk Access requirement using ssh. Find out how to stay safe!

One of the signature features of Apple’s macOS Mojave is user safety. As we noted here, 10.14 ushers in a raft of new security-related features that will change the way many people interact with the Mac operating system.

Many of these features are designed to stop Apple Events – the technology that underlies AppleScript, osascript, JXA (JavaScript for Automation), Automator, and a great deal of other interapplication communication – from accessing user data without explicit authorisation.

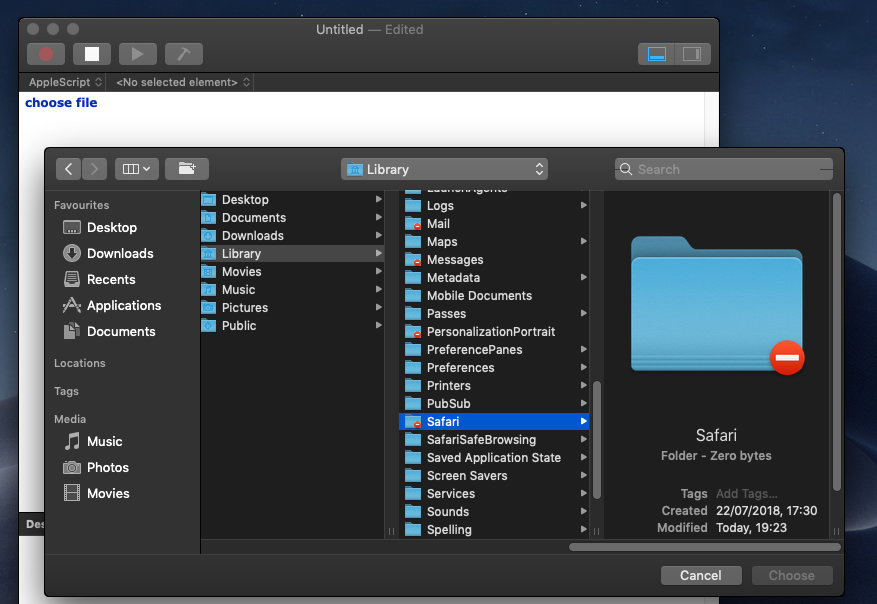

We can use Script Editor as an example of how the new protections are supposed to work. The simple AppleScript command choose file presents us with an open file dialog from which to pick files for use in a script. However, on Mojave, we see that certain folders in the user’s own Library are off limits:

These include Mail, Messages, Cookies, Suggestions and Safari. Note that users can browse into these folders without restriction through the Finder, but trying to do so through other applications is blocked by default.

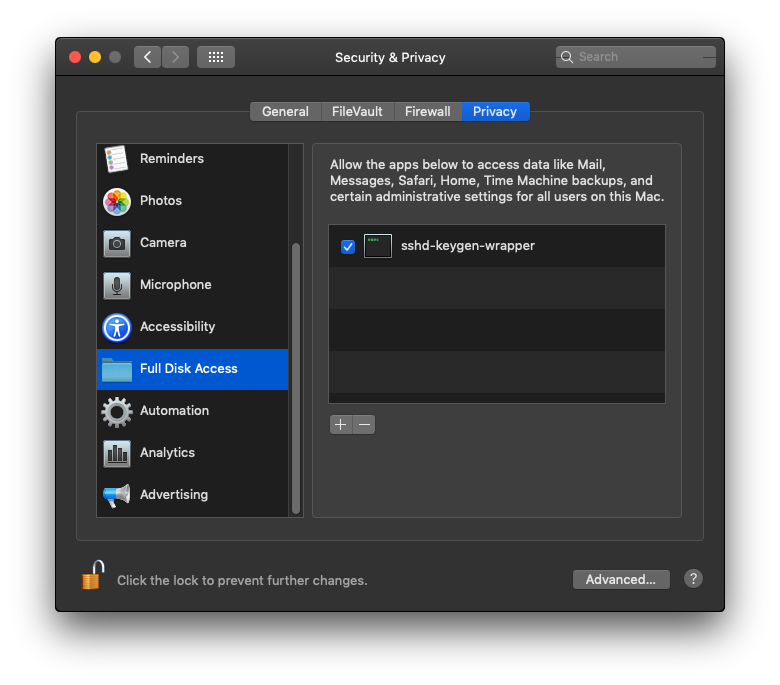

Interestingly, there’s no user feedback here to explain either the lack of access or how to deal with it. Users will have to discover for themselves that the workflow for accessing these folders is to go into System Preferences and manually add the app that they want to provide access for to the list of apps allowed in the Full Disk Access category in the Security & Privacy pane:

Once added and relaunched, the chosen app will then have permission to access all users’ protected folders on that Mac, just as they have on High Sierra and earlier versions of macOS. This process of discovery, we suspect, is going to produce a lot of IT Support Desk calls from frustrated users.

This “hardening” of user data in Mojave 10.14 is certainly a good idea given, for example, the recent revelations of Apple App Store apps abusing browsing history, but whether this will have much impact on bad actors seems doubtful for a couple of reasons.

Remote Bypass

The first reason is that there’s an oddity about the way macOS treats requests to access these areas. It turns out that it sometimes depends not so much on who is asking, but where the request is coming from.

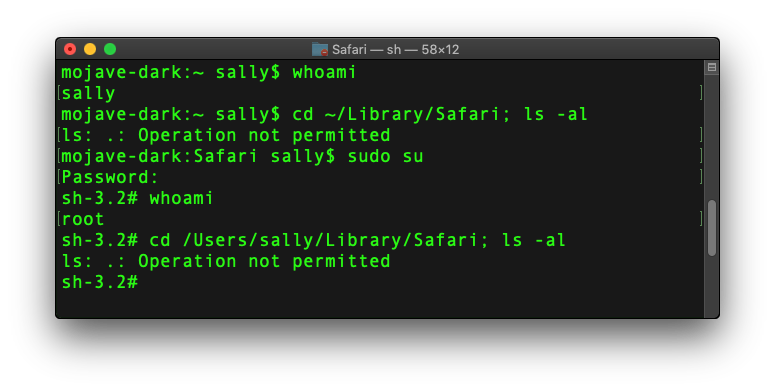

An admin user of the Terminal, for example, can’t cd into their own Safari folder, and neither can root:

Regardless of authentication and privilege level, macOS Mojave simply won’t allow Terminal to traverse those folders, just as it wouldn’t let Script Editor, if it hasn’t already been added to Full Disk Access.

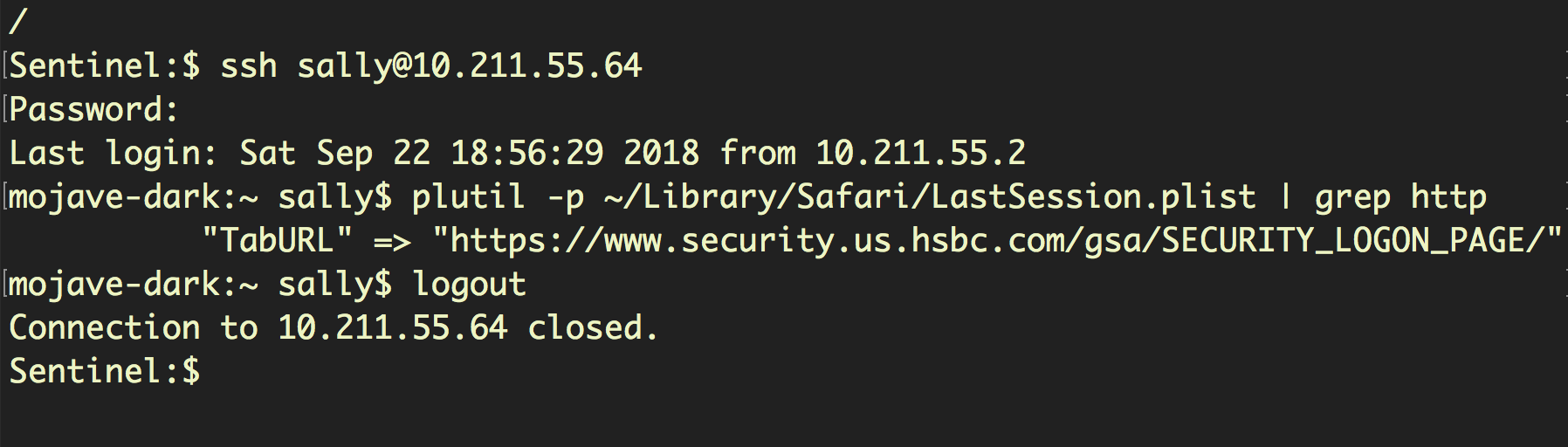

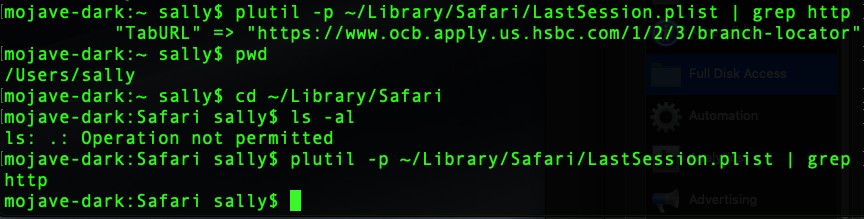

However, a remote attacker that has gained access to Sally’s admin credentials can go where neither Sally nor root can go:

Here, we have remotely logged in to Sally’s user account via ssh and retrieved the last website she visited, a banking logon page, by reading the LastSession.plist stored in the (supposedly) protected Safari folder.

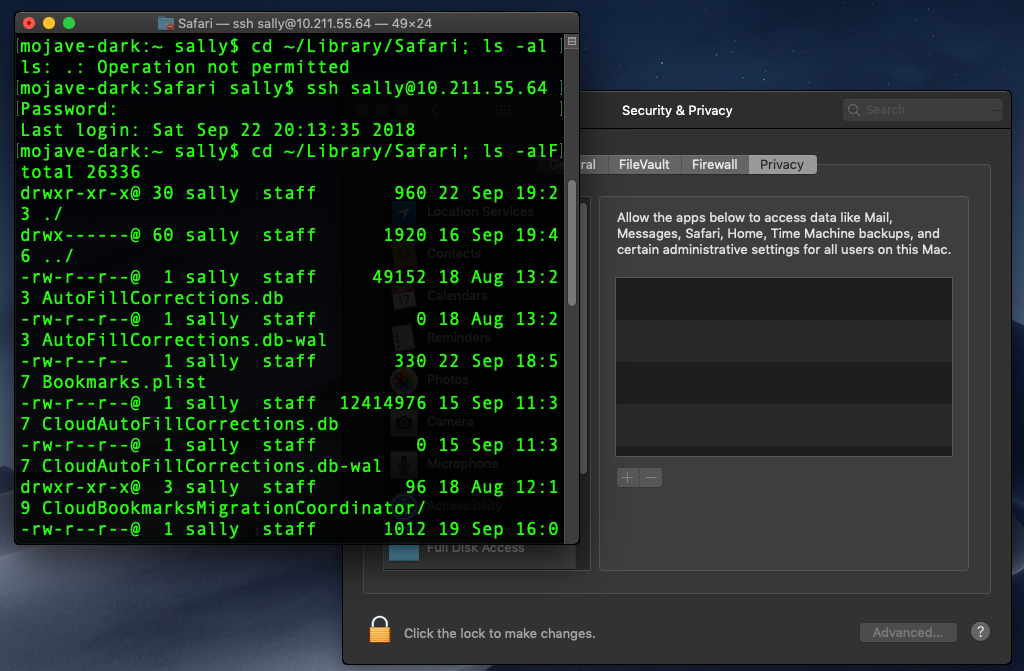

Importantly, the ability to ssh into the local account and traverse the protected folders does not require pre-approval of Terminal in Full Disk Access, and can even be performed locally by Sally herself with ssh:

In short, any local or remote user can bypass the Full Disk Access requirement simply by logging in via ssh. Fortunately, there is a way that this can be prevented as we’ll see in the Staying Safe section below.

Design Flaws

The second reason Mojave’s new protections may not prove to be much of a challenge for bad actors revolves around the way Apple have implemented Apple Event sandboxing and Full Disk Access. There are two issues here: dialog fatigue and universal allow listing.

Dialog fatigue will be familiar to admins who have despaired at the willingness of users to simply click-through every warning telling them not to do something regardless of the wording of the message. Requiring a one-click approval may be an extra step, but it is one with a low bar to overcome: most users become immune to these dialogs after the nth time that they have been presented to them by legitimate applications.

The upgrade to Mojave is going to be painful for a lot of users because so many regular apps, plug-ins, scripts and extensions will either be blocked or will throw such request-for-access dialogs. The history of similar attempts (think: MS Office and Macros) has taught us that by the time users have clicked through a dozen or more of such benign requests, the next malware installer to come along is likely to meet very little resistance from the weary user.

Universal allow listing for Full Disk Access is another problem from a security perspective. An app may request permission to do something seemingly innocuous (access a photo for one user, say), but the way Apple have implemented the approval mechanism means the app is now allowed for all users universally, so it can now read browser history, emails, chat messages and so on for every user, too.

This issue becomes more acute when we consider that many system apps – Script Editor, Automator, the Terminal – are going to be added by users to accomplish some specific task or other anyway. Thus, malware “living off the land” may often find that the resources they need have already been granted the permissions they desire.

Staying Safe

For administrators who wish to keep an eye on what has been added to the Full Disk Access privacy pane, the following command may prove useful:

sudo sqlite3 /Library/Application Support/com.apple.TCC/TCC.db 'SELECT * from access' | grep kTCCServiceSystemPolicyAllFiles

Of course, since this database is also included in Mojave’s new protections, it is a little ironic that you won’t be able to execute the command yourself unless Terminal has been added to Full Disk Access—and keep in mind what that means for user privacy—or you use the ssh bypass we mentioned above to avoid the new requirement.

For users and administrators who specifically wish to disable the ability to use ssh to access the protected folders, the following workaround appears to be effective.

- Use

sshto log in and traverse to one of the protected folders. - Open System Preferences > Security & Privacy > Privacy pane and click on ‘Full Disk Access’.

- Ensure that you see

sshd-keygen-wrapperin the list of items. You may alternatively or also seesshd.

If the list is empty, try reading or opening a file from within your ssh session. You may need to relaunch System Preferences before seeing the items in the list.

- Removing the items completely will not prevent the bypass; the items need to be in the list but disabled by unchecking them. Click the padlock in the bottom left after doing so to lock it:

- Test that your ssh session is no longer able to access the protected items:

The attempt to list a protected folder now returns “Operation not permitted”, while directly trying to read a file within it silently fails.

Take Aways

There’s no arguing that user data is safer in Mojave than in previous versions of macOS, but there’s a real potential for users to believe they are protected in situations when they are not, and that sense of false security is a danger in itself. Along with the relatively low bar for acquiring approval through dialog alerts, it seems inevitable that bad actors will continue in their efforts to abuse user privacy on macOS 10.14.