The Good

This week’s “Good” story also has a few sobering lessons. A Russian national has been arrested in the U.S. on charges of conspiracy related to an attempted cyber attack on electronic vehicle manufacturer Tesla. Egor Kriuchkov is accused of attempting to bribe a Tesla employee with an offer of $1m in Bitcoin in return for installing malware on the company’s network as well as providing details about the company’s infrastructure.

Kriuchkov, who was nabbed by the FBI as he tried to leave the country, allegedly told the unnamed employee that his Russian-based team of cyber criminals would first steal data from Tesla and then hit them with a ransom demand for $4 million dollars. The criminals intended to mount a DDoS attack at the time the malware was installed in order to distract the security team. Kriuchkov allegedly claimed that this method had been successful against other high-profile targets and had netted the gang similar amounts. It is believed that Kriuchkov may have been referring to the ransomware attack on Carlson Wagonlit Travel earlier this month.

Recruiting insiders as a means of breaching security controls is a technique one would normally associate with nation-state actors engaged in espionage, but clearly cyber crime gangs are also both able and willing to invest in the ‘long game’ too, particularly when the rewards are so rich. Kudos to the Tesla employee for thwarting what could have been, in the words of Tesla CEO Elon Musk, a very “serious attack” on the company.

The Bad

Unfortunately, for every attack thwarted, there are so many that are not. This week, researchers have detailed how notorious QakBot (aka QBot, QuakBot) malware has been evolving from banking trojan to malware delivery platform, not unlike Emotet, TrickBot and other so-called “Swiss Army knife” tools. Development this year has been rapid, with at least 15 iterations noted between January and August. Recent QakBot activity has been driven my malspam, but attacks have also been targeting the government and military, as well as manufacturing, across Europe and the United States.

QakBot’s success rides on the back of an MO that is depressingly familiar: a phishing mail leveraging a reply chain attack carries a poisoned document utilizing Visual Basic to download second-stage payloads and communicate with the attacker’s C2 (C&C) server. There is some suggestion that QakBot is also being delivered by rival platform Emotet in some cases.

The malware has the ability to function as a backdoor, and some variants contain a plugin that allows the operators to control the infected device by means of a VNC connection. Stealing credentials and harvesting emails for use in further malspam campaigns are primary objectives, but the malware can also recruit victims’ devices into a botnet and even use them as control servers for other machines. Researchers say QakBot operators have the ability to conduct bank transactions on the victim’s machine without their knowledge.

Source: Check Point

Defending against this malware, like so many others, is primarily a matter of stopping the initial vector of code execution through phishing. Users are also advised to look out for the usual lures such as job advertisements, COVID-19 and Election 2020 themed subjects, along with unexpected invoice and payment reminders.

The Ugly

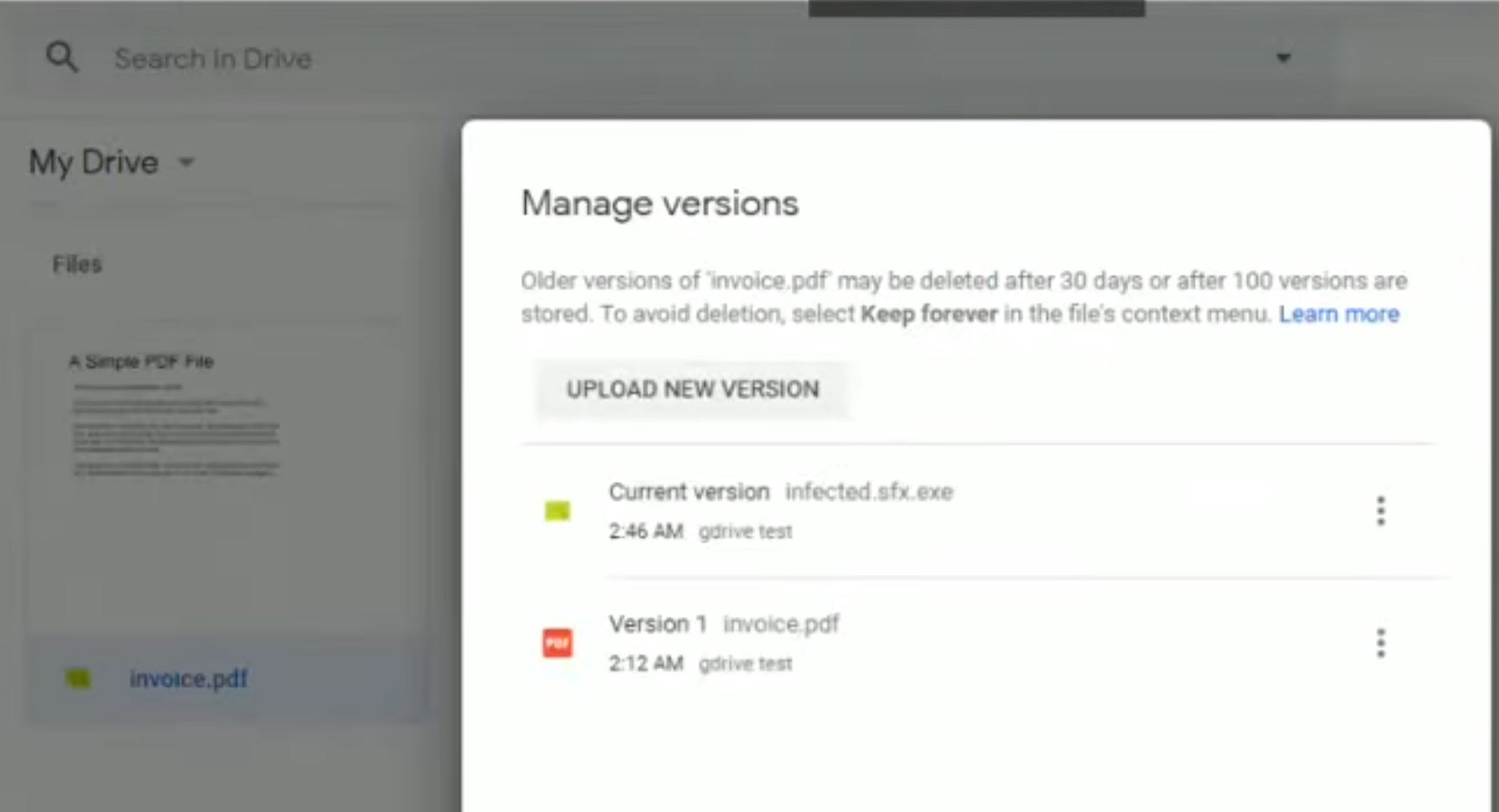

Attackers are always looking for new infection vectors, and what could be better for them (and worse for us) than an unpatched vulnerability in one of the world’s most widely used sharing platforms, Google Drive? This week a researcher discovered that non-executable documents uploaded and shared to Google Drive can be surreptitiously switched out for malicious executables without warning thanks to the Manage Versions feature.

The proof of concept shows that a file shared among users as, say, Invoice.pdf could be updated to Invoice.exe and the same link to the original file, if clicked, would now execute the malicious file without any warning to the users. To make matters worse, despite the fact that some anti-malware tools might recognize the file as malicious, Google Chrome appears to implicitly trust anything downloaded directly from Google Drive.

Being able to change file version without doing a check on the file type seems like a dangerous flaw that attackers could exploit in spearphishing campaigns: share an innocent file with a user, encourage them to collaborate, then switch it out for malware, and the next time they visit the link…

It’s not immediately clear from the report whether Google plans to address this problem in the future, but until Google enforce file type validation in the ‘Manage Versions’ feature, this is a risk that all Google Drive users should be aware of.