Exploiting Trust

When we think of the word ‘trust’, what thoughts jump to the forefront of our minds? It initially evokes thoughts of personal relationships, with our closest family members and long term friendships or colleagues, where you know those individuals are consistently and reliably there for you. They are trusted for their authenticity, their integrity and honesty, they listen to you and ultimately are discreet with your information. However, that trust as we have often experienced is something that is fragile and easily damaged. While it is implicit for some relationships, for others, it is easier to lose that feeling of trust.

If we relate trust to the information security industry and the third party tools and systems that we implement to help secure our organisations, then the same concepts hold true. We place our trust in security systems that have earned trust by proving to be reliable and consistent, by demonstrating integrity, value and confidentiality, through a trusted network of recommendations amongst many other data points.

That trust is used to help us manage and mitigate risk and in turn helps other business relationships place their trust in us, and so trust is chained together from business to business, supplier to supplier, vendor to vendor.

However, when we select a security system to help protect ourselves, we are also accepting hidden areas of trust: relationships that you are unaware that you have agreed to, ones that were made on your behalf in a chain of relationships beyond your immediate control. These chains sometimes have weak points, areas where a gap has been identified, where a process or tool might not be quite as robust as yours, and this is what the supply chain attackers in the last 10 years have looked to exploit.

Supply chain attacks look to areas of trust that are fragile. Weaknesses in these chains can be used to bypass the implicit trust you have in your own security systems, processes and organisations. Something you were, until that point, completely unaware of.

In this post, we will explore some of the high-profile examples of where these chains have been compromised and look to learn lessons from these incidents, to help identify trust weaknesses and help mitigate potential future problems.

RSA Security – 2011

Back in 2011, RSA – the security division of EMC – was attacked and critical SecurID product secrets were stolen. These secrets would allow an attacker to clone and replicate the two factor authentication system supplied by RSA.

RSA SecurID token at the time was a very popular hardware based (something you have), six digit, one-time token-based password system used by companies to reduce the reliance and insecurity of static usernames and passwords. By breaking into RSA, the attacker accessed product seed data that compromised up to 40 million tokens in the field.

The attackers’ ultimate goal was to target military secrets held by Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, but they had been prevented from doing so by those organizations’ use of the strong authentication token supplied by RSA.

Organizations had placed their trust in the RSA SecurID system to provide an additional layer of security, and the attackers bypassed the trust of this system by targeting the supplier of the tokens directly.

At the time, the attacker employed a zero day vulnerability in Adobe Flash Player to inject their backdoor, delivered by a phishing email to an RSA employee.

CCleaner March 2017

In March 2017, the hugely popular computer cleaning software called CCleaner was compromised by an attacker to help distribute their malicious code to unsuspecting victims that used CCleaner as a trustworthy tool. It was a devastatingly successful attack, which reportedly led to approximately 1.6 million downloads of the infected copy of CCleaner.

The attackers compromised the maker of CCleaner’s network to inject their software, known as ShadowPad, into the application. The attackers were specifically targeting a smaller group of companies and some eleven of those targeted were successfully compromised by the backdoored CCleaner application.

NotPetya June 2017

The NotPeyta attack of summer 2017 involved a ransomware-style attack which encrypted data and in some cases also destroyed the MBR (Master Boot Record) of infected computers.

This attack leveraged the Shadowbrokers recently released Eternalblue and EternalRomance exploits, which took advantage of vulnerabilities within the SMBv1 (Server Message Block) protocols for computers running MS Windows. These were the same vulnerabilities that were used in the WannaCry outbreak earlier that year.

A similar theme of leveraging the trust in the supply chain was implemented. The attackers used a legitimate software package update mechanism of a company called M.E.Doc, a financial software package predominantly used by Ukrainian financial institutions, to launch their attack. While it was clear the target of the attack was Ukraine, the attack quickly spread elsewhere.

What became most interesting was that the encrypted computers were not designed to be decrypted; therefore, the purpose of the attack was solely destructive rather than a financially-motivated ransomware attack. It is widely accepted that the financial impact of this attack was in the region of $10bn.

ASUS Software Update 2019

In 2019, computer manufacturing giant ASUSTek Computer – more commonly known as ASUS – identified a problem with its live update service, learning as a result that it had been compromised earlier in 2018. The compromise allowed this supposedly legitimate and trusted software to deliver malware to thousands of ASUS customers.

According to one report, it impacted 13,000 computers; 80% were consumer customers, and the remainder were businesses. However, the 2nd stage malware was highly targeted via a list of specific MAC addresses. Malicious versions of ASUS’ Live Update software (normally used to deliver updates to ASUS components and applications), was found to be installed and used to deliver a secondary payload of malware.

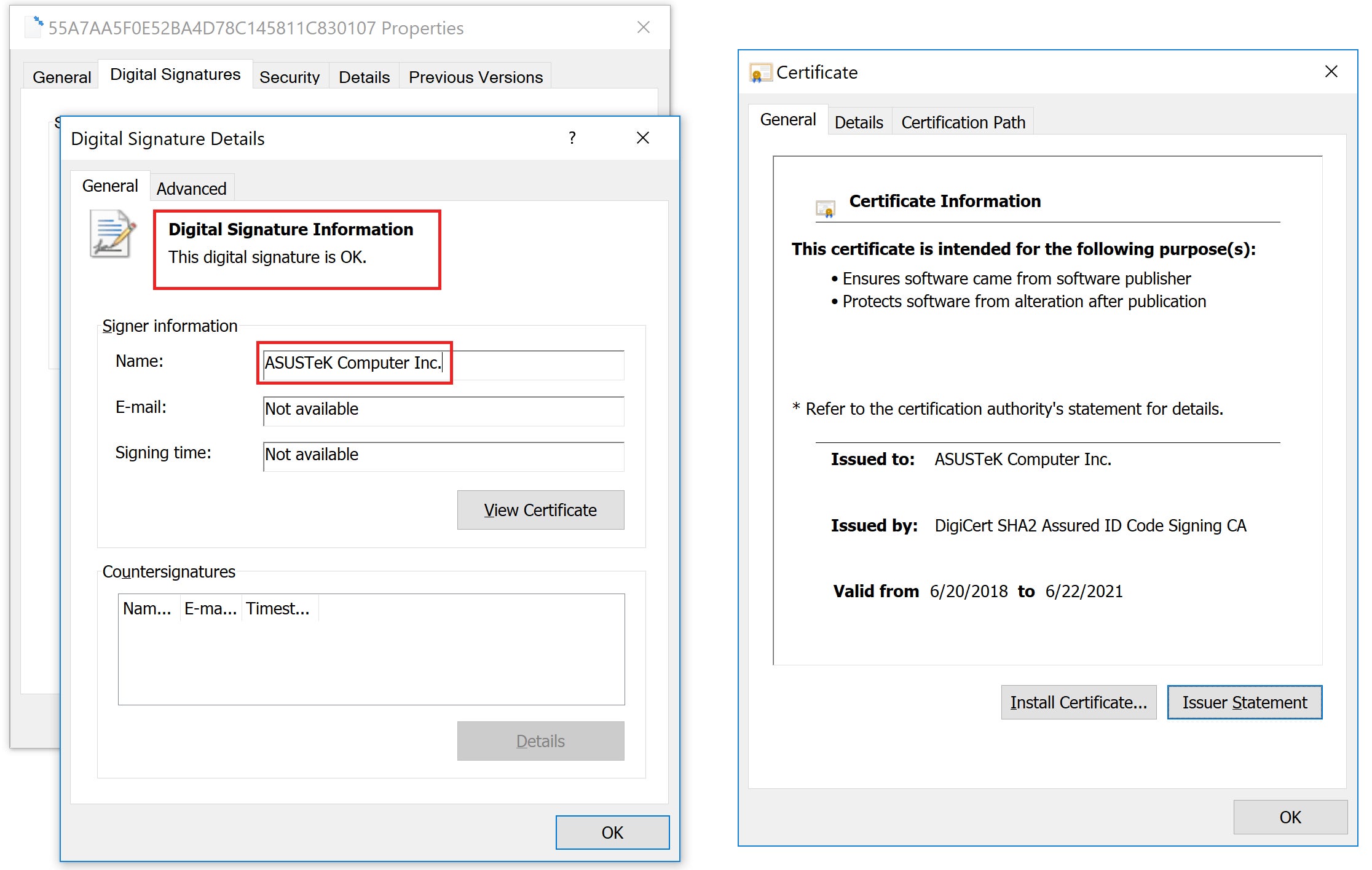

What was most interesting about this attack was that the version of ASUS Live Update that was compromised to deliver malware was legitimately signed by an ASUSTek Computer certificate. By obtaining access to the signing authority for this application, the attackers were able to effectively bypass the trust relationship that had been placed in the certificate infrastructure.

In 2020, responsibility for the ASUS supply chain attack was attributed to APT41.

SolarWinds December 2020

While there seemed to be a temporary lull in supply chain attacks after those mentioned above, the Solarwinds attack put them firmly back on the map back in December 2020.

SolarWinds is a widely trusted software vendor with some 300,000 customers, but as the story unfolded it became clear that their Orion software had been severely compromised. The attackers managed to incorporate their malware into a legitimate Symantec certificate, which was used to update the SolarWinds software.

After further investigation, SolarWinds reported that there was evidence that the malicious code was placed into their software and updates between March and June 2020. They also reported that they believed it to impact some 18,000 of their customers.

The SolarWinds attack was highly sophisticated. For example, the malware was sandbox aware and only activated after 14 days of dormancy. Given the nature of the targets impacted, such as US government institutions, and the attackers level of sophistication, it was rapidly apparent that the threat actor was APT in nature, and now widely attributed to the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR).

Kaseya July 2021

Fast forward to summer 2021 and the discovery that Kaseya VSA software, responsible for monitoring and troubleshooting endpoint computers and widely used by Managed Service Providers to help support their customers, had also been compromised. An update to the VSA software included a ransomware component that went on to compromise some 1500 customers. The attackers leveraged two vulnerabilities, one known since April 2021 and the other since July 2015, in the VSA software.

What is most interesting about this particular attack is that the motivation seemed to be purely financial as the attackers were initially asking $70M for the recovery of the decrypted data of their victims.

This attack leveraged the REvil group’s ransomware. It is also worth noting that the delivery vehicle of the ransomware was only the externally facing Kaseya VSA infrastructure, exploited by known vulnerabilities rather than through an internal breach.

Supply Chain Attack Commonalities

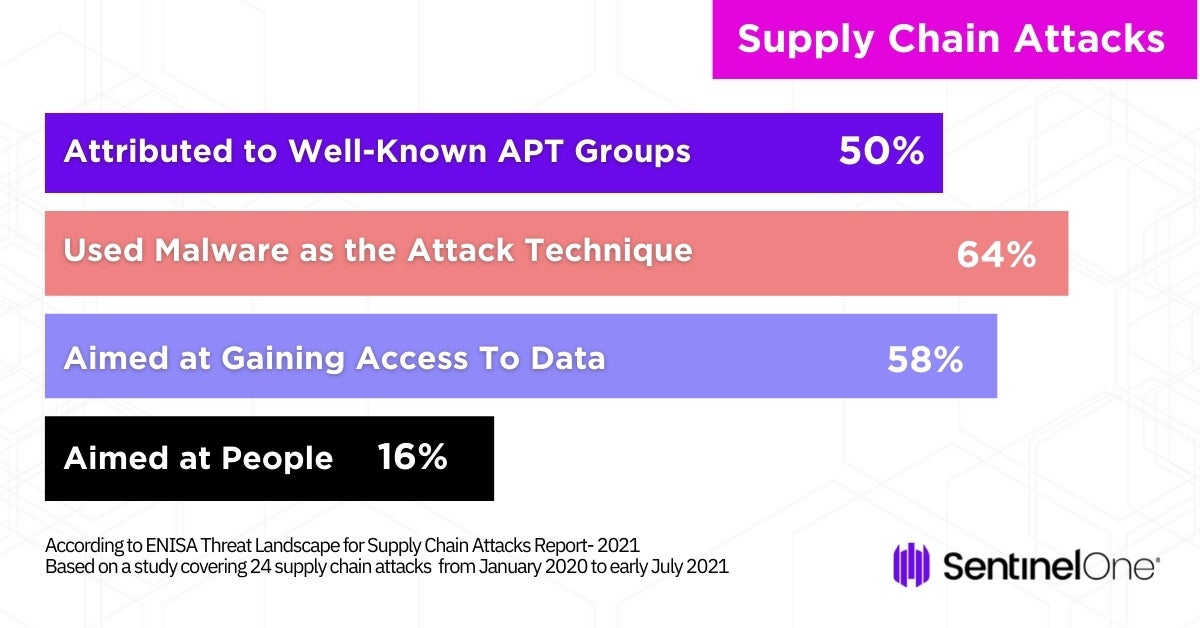

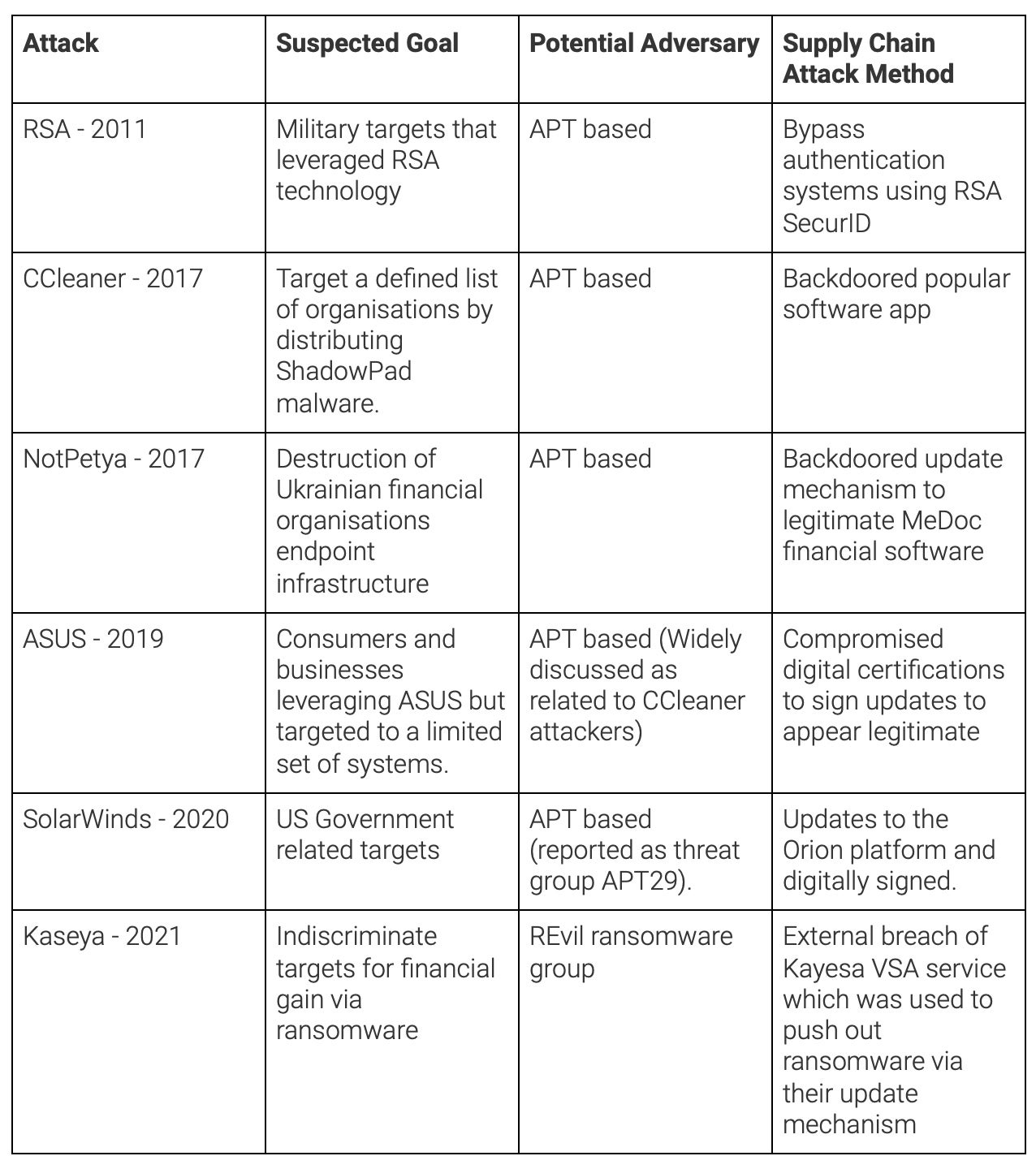

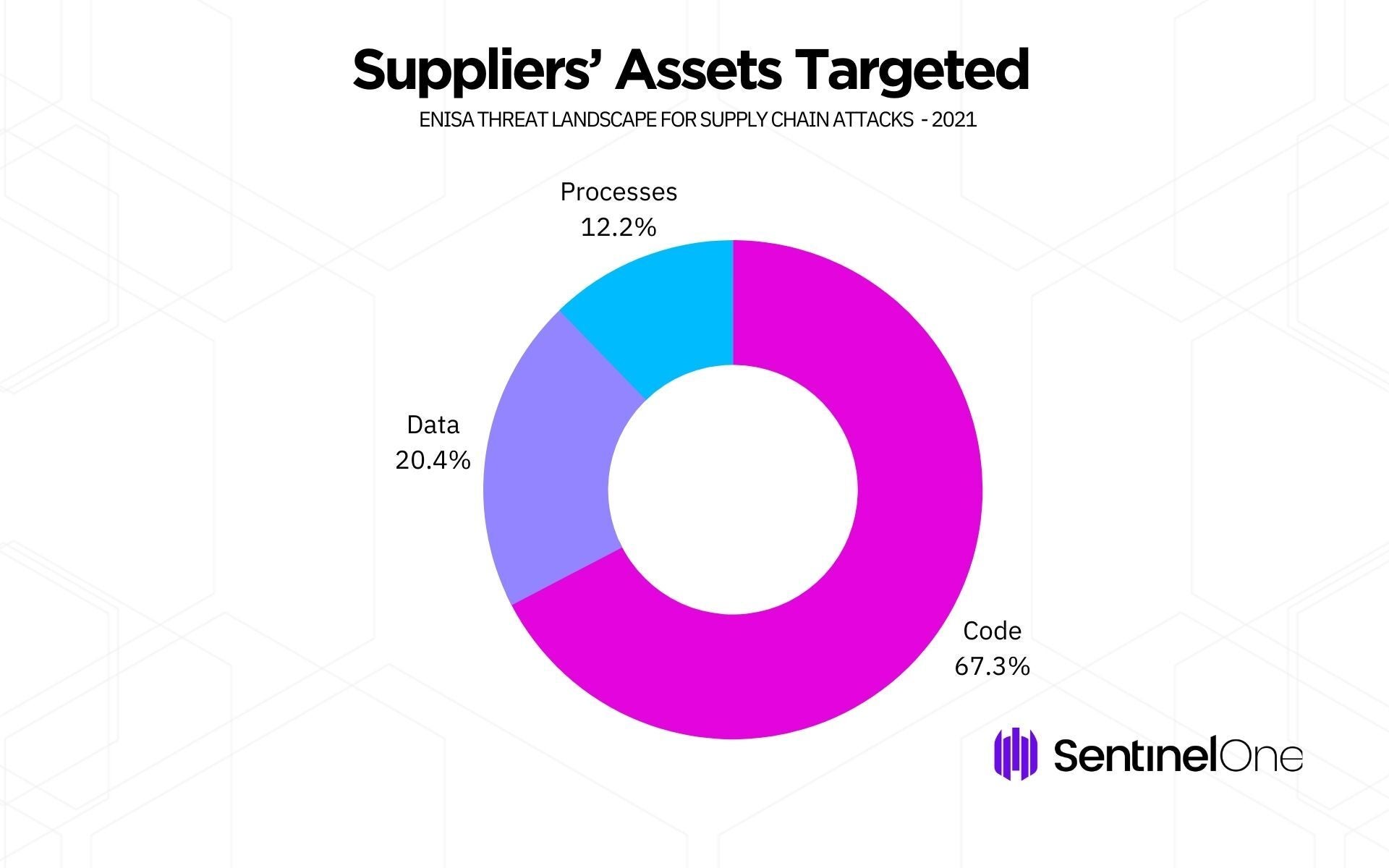

Analysis of these examples shows that adversaries are often either manipulating the code signing procedures via compromised but legitimate digital signing of certificates, hijacking the update distribution network of an ISV solution, or compromising original source code.

The majority of the attackers have a high sophistication level, with the exception of the recent Kaseya attack, which leveraged an external facing service with known vulnerabilities.

Preventing and Mitigating Supply Chain Attacks

Attackers always attempt to take the least path of resistence. Today, it’s often done by first compromising one of the end targets’ upstream suppliers and then abusing the trust relationship that they have to the true target to obtain their goals.

Naturally when we think of our technology defenses, we expect to be facing out, expecting the attackers from the outside, whereas, these supply chain attacks exploit a trusted component within our environments: just where we are most vulnerable and where we have the least visibility.

As part of any organization’s risk management program, supply chain attacks must be factored in, so what are the typical processes for compliance, governance and technology areas that could be bolstered to help mitigate these problems?

- Develop and implement a vendor risk management program to evaluate, track, and measure 3rd-party risk.

- Enforce through contractual requirements vendor cybersecurity assessments, including for the vendors own supply chain risk.

- Require ISO 27001 certification or CMMI and/or comply with cybersecurity frameworks like NIST or CIS

- Plan to move to a zero trust network (ZTA) architecture ensuring that all identities and endpoints are no longer trusted by default but instead continuously validated for each access request.

- Deploy a modern, platform-agnostic XDR platform capable of detecting and remediating sophisticated attacks across your endpoints, cloud and network infrastructure.

- Enforce multi factor authentication (MFA) to prevent the most typical of authentication brute forcing attacks

- Increase your network and endpoint visibility retention rates so that long lasting attacks can be identified. (the SolarWinds attackers were present for at least 5 months before launching their outward-facing attack)

- Be exceptionally careful as to how and where you configure your endpoint tool exceptions. Being overly permissive here with tools that you supposedly trust could lead to detection gaps.

- If you are an ISV then ensure best practices for Secure Development Lifecycle (SDL), vulnerability assessment and patch management programs to address identified issues.

Conclusion

The real challenge with these sophisticated supply chain attacks are that they leverage the implicit trust we place into our 3rd parties and also the implicit trust we place in the tools we use to support our businesses.

The real benefit to the attacker is that if they are successful, they have potentially increased their ability to scale the targets that they can infect, as well as allowing them the benefit of going completely undetected for potentially many weeks or months in length, depending on the goal of the attack.

It is essential that organizations review their cybersecurity requirements, gain visibility into supply chain dependencies, and deploy a modern XDR platform that can identify and contain a breach even if it originates deep within the company’s own supply chain.

Want to know more about how SentinelOne can help? Contact us for more information, or request a free demo.