In this guest post, Tal Eliyahu and Begum Calguner explain in rich detail the entire process behind automated account takeovers and how they caused over $4bn of losses in the previous year alone.

Living in an era of data privacy dystopia, having an online presence comes with the direct opportunity cost of “being pwned”. In a data black market fueled by both legitimate and illegitimate players, cybercriminals not only transact amongst themselves but also with large corporations for stolen data.

As a matter of fact, the number of data breaches as well as the average cost of a data breach continues to soar. Having to self-regulate in the ever-expanding field of cybersecurity, the obscurity of privacy interpretations and awareness causes tech leaders to opt for biometrics as the primary authentication method while retiring the traditional password-based user logins, despite public satisfaction with using passwords. The misperception lies in the fact that, with opting for biometric authentication instead of passwords, users gain the ultimate blend of user experience (UX) and security. However, biometrics-supported authentication methods don’t always manifest as foolproof or user-friendly.

In light of the above, public trust in technological business has diminished, which is subsequently reflected upon those businesses financially. This situation is charged by the new dynamic challenges such as data access rights exploits brought by the adoption of privacy laws and regulations.

The Official Definition of ATO

“An account takeover can happen when a fraudster or computer criminal poses as a genuine customer, gains control of an account and then makes unauthorized transactions. Any account could be taken over by criminals, including bank, credit card, email, and other service providers. Online banking accounts are usually taken over as a result of phishing, spyware or malware scams. This is a form of internet crime or computer crime.” – ActionFraud a service provided by City of London Police.

Key Figures Illustrating the Magnitude of Account Takeovers Currently

“Account takeover placed among the top three types of fraud reported from a whole 96% fraud attack reported by eCommerce businesses.” – MRC 2019 Global Fraud Survey

“89% of executives at financial institutions said that account takeover fraud is the most common cause of losses in their digital channels” – Aite Group

“Account takeover accounted for $4 billion in losses last year, which was slightly down from the year prior ($5.1 billion), but was up significantly when compared to data in recent years.” Javelin Strategy & Research

“The large majority of compromised accounts are in a dormant state…65% of these accounts belong to users that have not logged in for more than 90 days, and 80% of these accounts belong to users that have not logged in for more than 30 days.” – DataVisor

“29% of breaches involved use of stolen credentials.” – Verizon Data Breach Incident Report 2019

Role of Credential Stuffing in Automated ATO Attacks

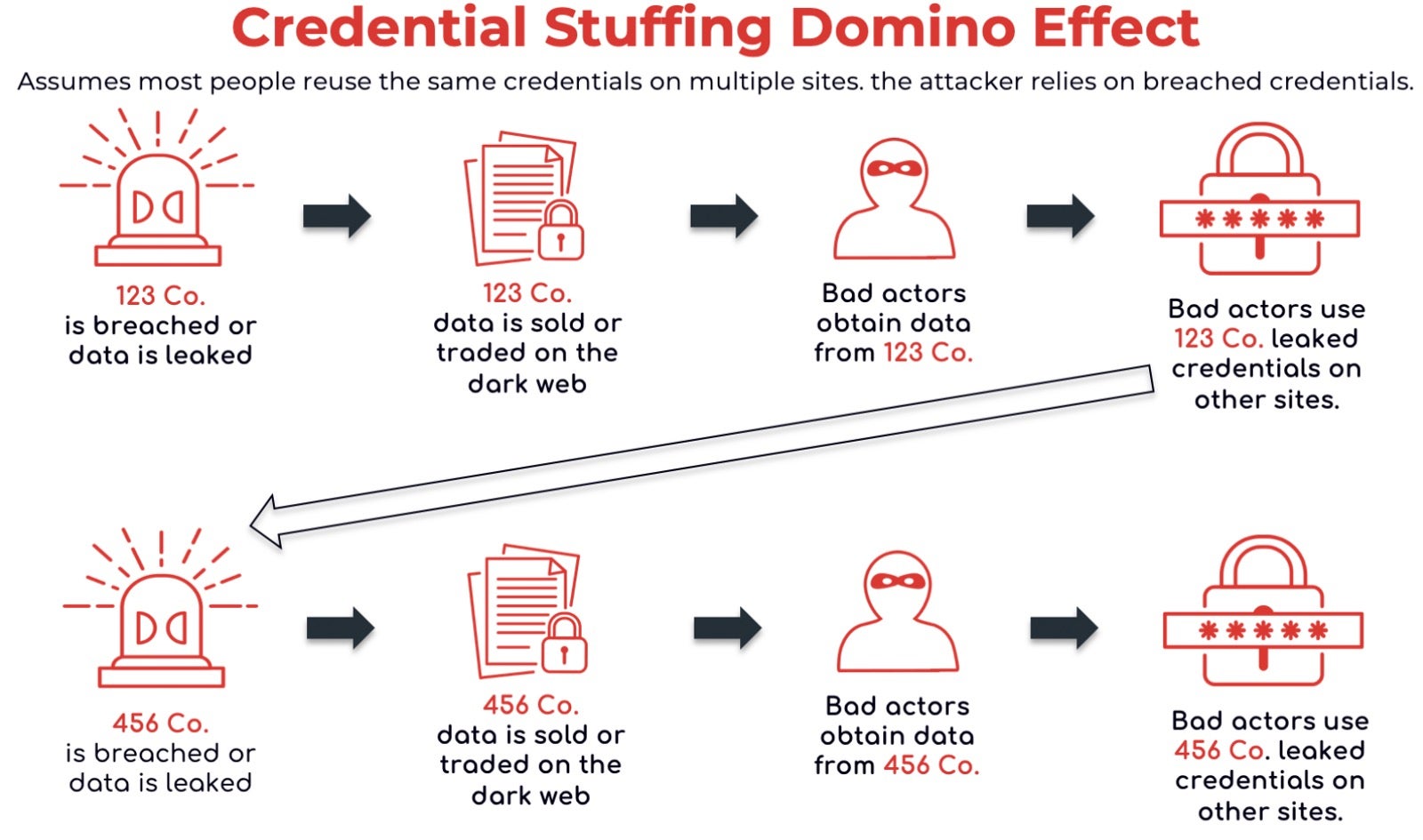

Criminals gather billions of login credentials via data breaches occurring in low profile websites. With credential stuffing, they then exploit the tendency of people to reuse the same password and username combination even on higher profile websites.

The repeated use of passwords increases users’ likelihood of having their credentials already existing within an already-breached ‘combo list’ (e.g., “Collection #1-#5”). With free services at the disposal of the criminals such as people search to gather user credentials as well as tools utilizing combo lists to automate their credential stuffing attacks, criminals can streamline the data breach, and achieve a higher succes rate of account takeovers.

“From January 2018 through June 2019, more than 61 billion credential stuffing attempts” — Akamai, State of the Internet

In short, combined with a user propensity to use the same password on a myriad of platforms no matter if it is high or low profile, many websites accepting email address/phone number as a valid, alternative username simplifies the attack even further for the criminal: one username with a repeatable set of passwords for all the accounts belonging to the victim.

The two main types of threat from credential stuffing attacks are coordinated mass-scale automated threat attacks based on sophisticated techniques and targeted attacks. While preventative measures exist for the common user against the former, there is little that a less tech-savvy user lacking cybersecurity awareness can do to hinder being the victim of the latter type.

In spite of the fact that mass-scale automated threat attacks may usually be avoided by users enabling two-factor authentication (2FA) on their accounts, this is not as vastly adopted by users as commonly believed. Even for services such as e-mail accounts, which store data of the utmost sensitivity with integration to various other 3rd party platforms and services, 2FA is not mandatory for users on many platforms.

According to reports, amongst over 1.5 billion active Gmail users, 90% do not have 2FA enabled. Even though Financial institutions’ (FIs) accounts are perceived as the most important type of account to secure for users based on surveys, FIs still facilitate credential stuffing attacks by not enforcing the usage of 2FA for account access.

Due to the continuous dilemma of keeping a safe balance between UX versus security, firms opt to serve 2FA as a recommended option rather than imposing it upon users as a mandatory practice. However, not enforcing 2FA from the start leads into additional authentication layers (i.e., static and dynamic knowledge-based questions and more), thus halting the user experience at later stages. And for all that, each of the above-mentioned authentication controls can still be bypassed by criminals.

Cybercrime as an Industry – Status Quo

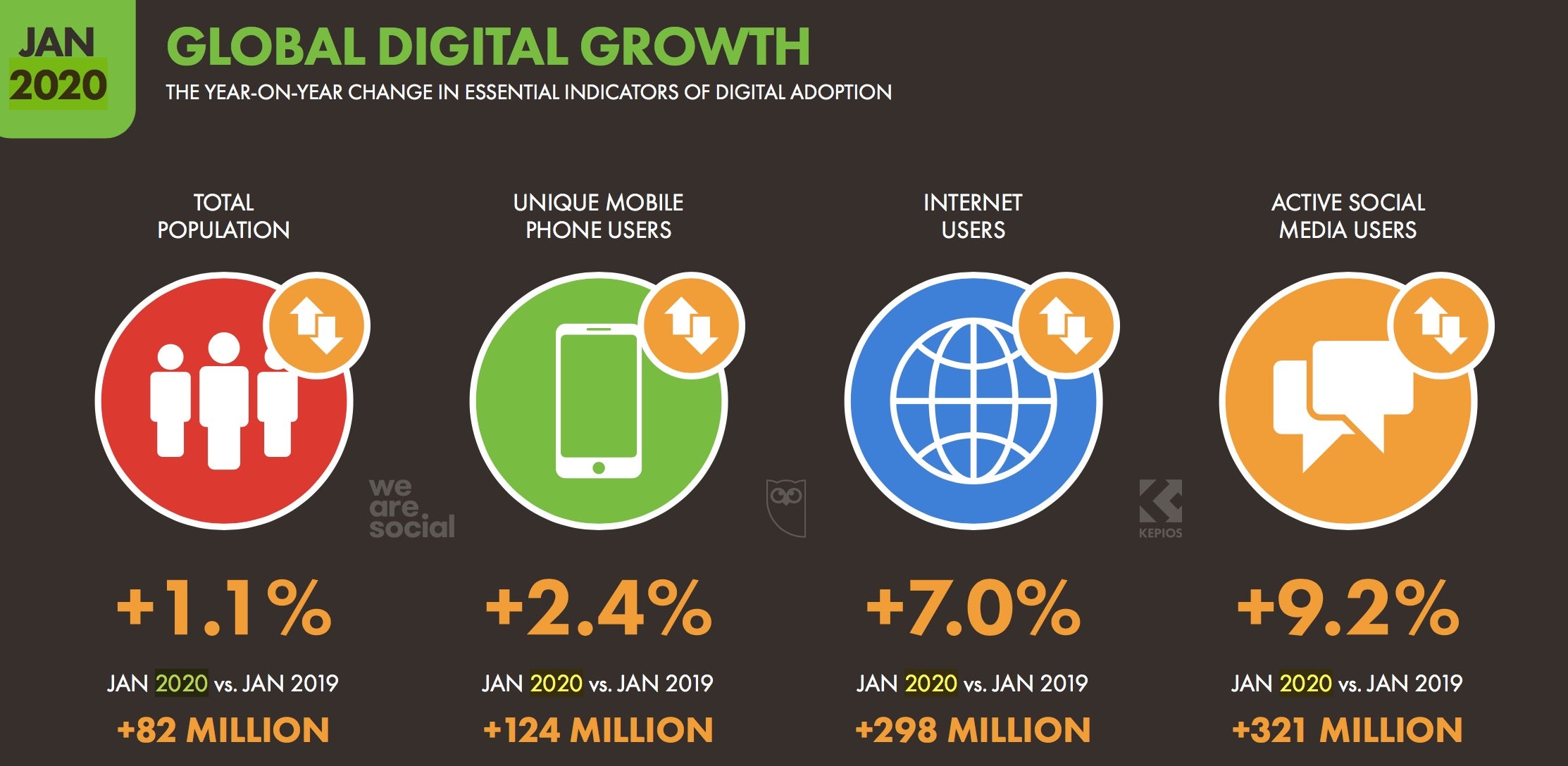

Cybercrime as an industry, although illegitimate, operates according to the same principles of keeping any business afloat, which is to attain and preserve a positive return on investment (ROI). Thereupon, with the continuous growth of the target group known as the ‘client pool’, combined with internet users’ lack of password hygiene awareness, the cybercrime industry offers many opportunities that can be capitalized on, which can also minimize the cost of successful attacks. As a matter of fact, this creates a technological race between the criminals, technology evangelists and entrepreneurs and the cybersecurity industry, where criminals adopt emerging technologies and develop advanced automation for attacks and new tactics and techniques to bypass security measures, while the cost to business of implementing and adjusting security measures against cybercrime continues to increase.

Impact of the Growth of Targeted Population on Criminal Strategies

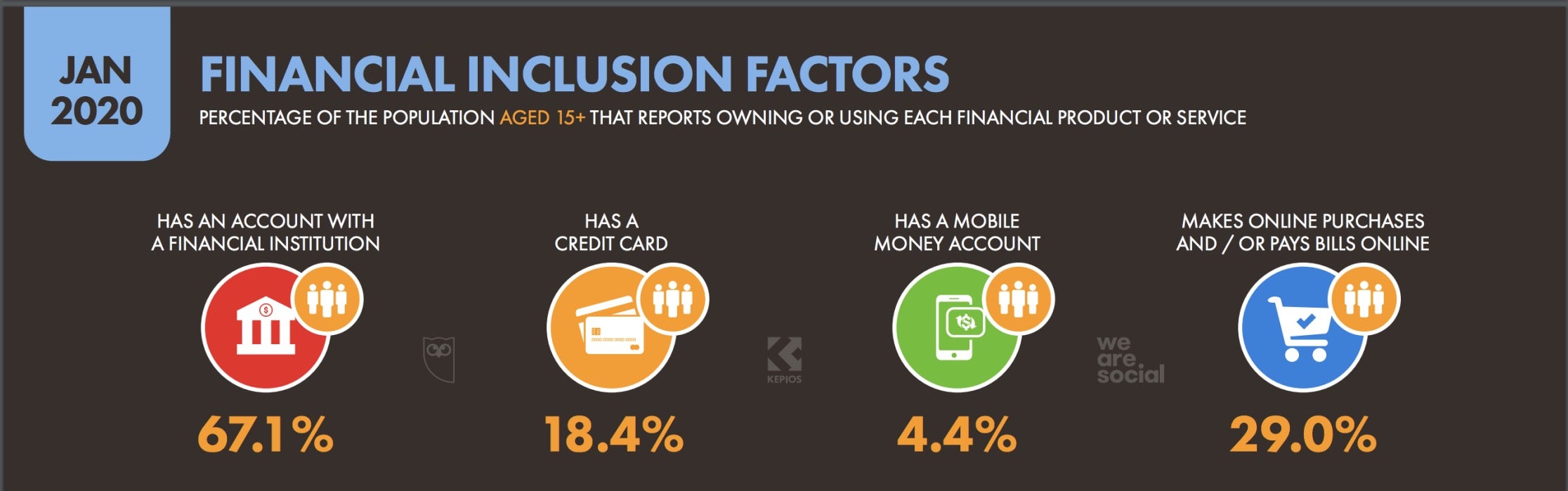

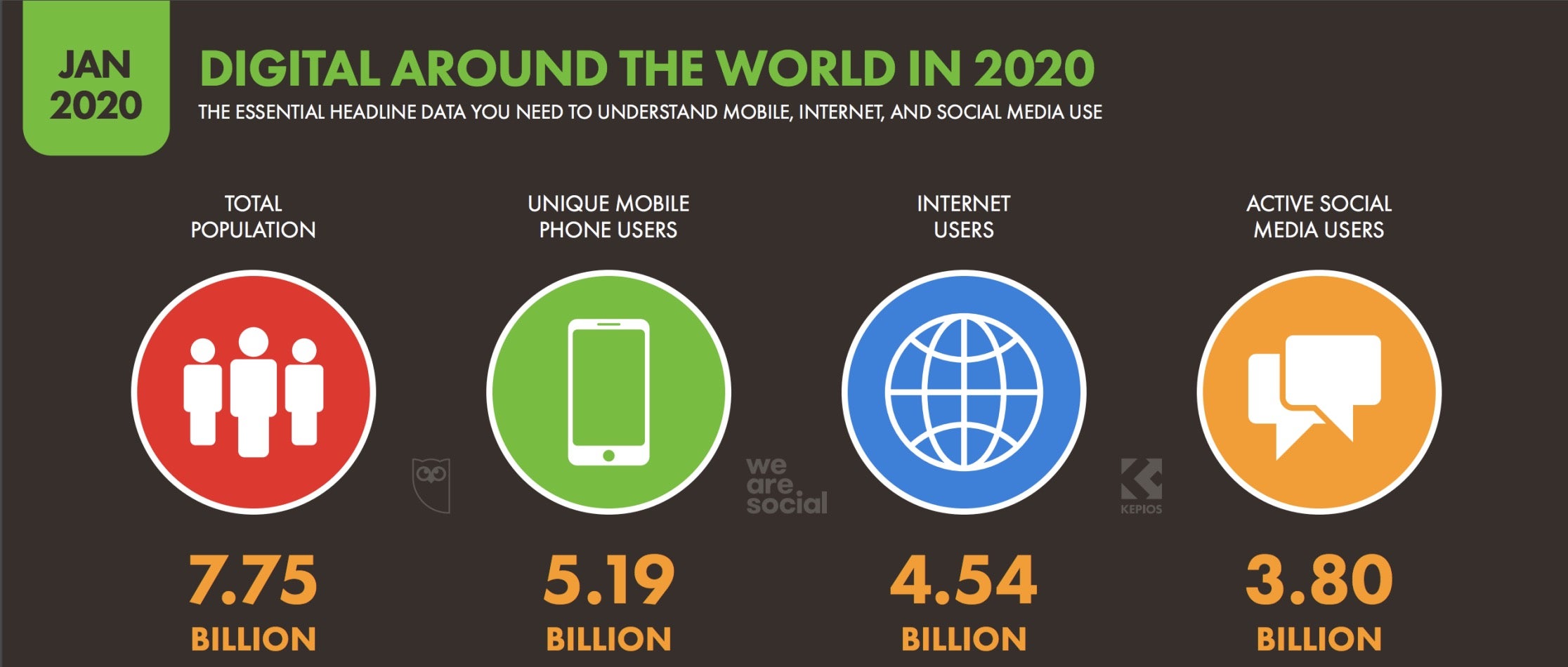

Amongst a rising population of 7.75 billion people, the number of internet users has increased from 2.4 billion to 4.54 billion since 2014. Bearing in mind that of those 4.54 billion, 3.76 billion use mobile and web payment methods for products and services, credential stuffing attacks present a lucrative option for criminals.

Just within the first quarter of 2019, 281 data breaches exposed more than 4.53 billion records, while 1 million usernames and passwords are reportedly spilled or stolen daily.

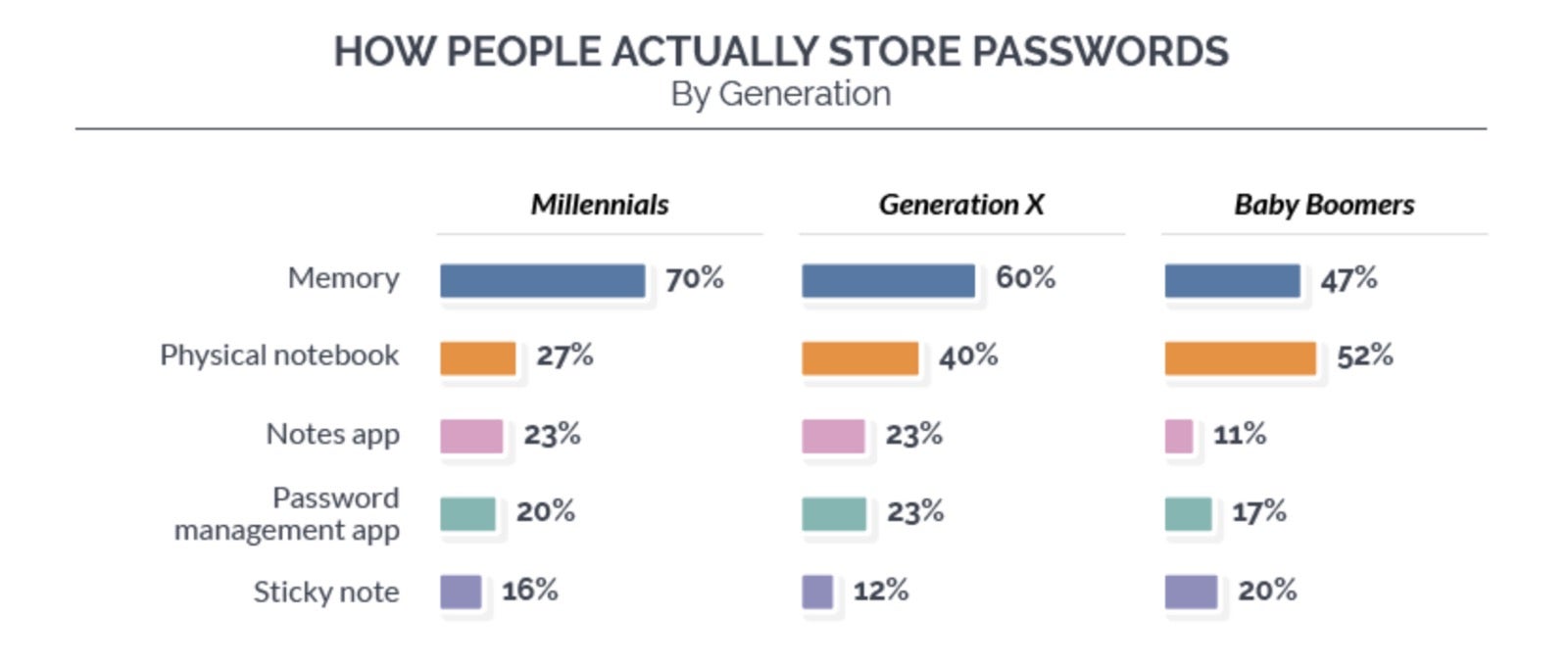

Different demographic groups of internet users manifest online behavioral patterns specific to their demographic group and present distinct vulnerabilities for criminals to take advantage of. Identifying the target clients via client pool segmentation, based on their key weaknesses and their associated financial stats, optimizes the ROI of the credential stuffing attacks for criminals (highest revenue for the effort and time invested). It would be worthwhile to note that the age-based segmentation of the client pool depicts the proclivities of the behavior patterns of millennials and seniors to the attackers.

“Criminals Steal $37 Billion a Year from America’s Elderly” – Bloomberg

According to reports, a standard user with an average of 90 online accounts requiring passwords, will reuse the same passwords 4-6 times. When required to update, 68% of users only tweak their previous password slightly. In addition, the majority of users still rely on “saving passwords” through memory: meaning, they create passwords that are easy to remember (and thus, guess) rather than making high-entropy passwords and saving them in password manager software. At the other end of the spectrum, securing the account credentials using password managers also possesses certain vulnerabilities, including creating a single point of compromise.

Criminals predominantly use automation for credential stuffing by means of tools known as “bad bots”. Bots are software programs operating online to perform repetitive tasks. While constituting 20.4% of the total website traffic, only 21.1% of them are categorized to be the sophisticated type also known as All-in-One (AIO) applications. Notable tools used by criminals are “SNIPR” ($20), STORM, MailRanger, and SentryMBA. Competition amongst hackers encourages other hackers to reverse engineer existing tools to optimize the flaws and release cracked or pirated versions back into the market. Even legitimate tools like OpenBullet are utilized by criminals as “access checkers”. Such tools are renowned for their strong community support, using uploaded configuration files programmed to generate sequenced API calls, and their ability to automate browsing processes using scripting languages (e.g., PhantomJS, trifleJS and others) with browser emulation libraries (Puppeteer, Selenium, etc).

Criminal Adoption of Innovation

Despite the abundance of community support for traditional, manual and arduous attack techniques available for a range of prices in web forums, criminals consistently endeavor to maximize the capabilities of the latest automation techniques with growing community support on contemporary, detection resilient instant messaging groups (i.e. “‘Dark Work’’) or even on legitimate freelancer and mechanical turks platforms.

Supplemented by collaboration and information-sharing amongst criminals, the adoption of the latest automated techniques has been ousting the aforementioned laborious human tasks while adding further layers of sophistication for superior and speedier results utilizing AI-enhanced systems to elevate bad bots to beyond level 2 automation.

Bad bots are highly sophisticated, automated robots devised to function in stealth mode and to mimic behaviors via their built-in deception and evasion capabilities that help to surpass detective and preventive security controls.

With the use of rotating VPN, secure VPS, RDP servers or residential, secure and other clean proxies, the location of the targeted victim can be simulated with a 5-mile precision. Furthermore, bad bots evade anti-fraud control measures with the help of a digital mask containing not only unique behaviors of the victim (e.g., tap touchscreen frequency) and browsing patterns (e.g., screentime or fields of user interest) but also the victim’s device fingerprint (e.g., device ID, OS version) using doppelgangers.

The development of such countermeasures in order to evade bot detection controls like Google’s reCaptcha and other traditional controls that once required human involvement goes to show just how advantageous such advanced bots are for credential stuffing attacks.

Even the case of the bot maxing out the number of login attempts, triggering a lock-out challenge or generating suspicious activity causing account lockout can pose a revenue stream for the criminals. Receiving notifications at their back-office once an account is locked out enables the criminals to initiate second and third layers of ATO attacks immediately. Usually, swiftly after the failure of the second layer attacks (e.g., abuse recovery options), the third layer of attacks commence by sending the victim’s account details to a pseudo support center to “alert” the victim of the locked out account. This facilitates “escorting” the victim to give remote access to his or her account, to unlock the account or even to share the details received in an email or SMS to reset their passwords per request, hence resulting in an ATO. As a matter of fact, criminals manage to turn the tables in their favor in spite of the roadblocks they encounter.

Criminal Leveraging of Alert Fatigue

More than half of global corporations are estimated to be neither ready nor prepared to handle a large scale cyber attack, lacking highly skilled cybersecurity staff let alone a cybersecurity lead; ergo, they are creating the circumstances for cybercrime to flourish.

Based on internet traffic, bad bots can be considered the permanent residents of the digital world with just one step away from being official dominant digital citizens. While for detection avoidance, bad bots are developed to stay in stealth mode during credential stuffing attacks by replicating any good red team operation, being empowered with AI automation capabilities equips them with the art of storytelling as has been observed lately in automated breach and attack simulation (BAS) solutions.

With the deception created by storytelling, bad bots’ activity may be perceived as “white noise” and tagged as false positive alerts amongst 50% of the reported alerts, non-priority alert or under scoped incidents from the overwhelming 25K daily events that can last for several days on average, according to SecOps analysts. Bearing in mind the daily average of 20 alerts each with the duration of 20 mins for analysts to investigate as well as the limited training of 20 hours annually they receive, analysts’ wasting over half of their day looking for problems that are either insignificant or not really problems at all is inevitable. Akin to the domino effect, the waste of resources impairs the KPIs and eventually benefits criminals.

“50,000 Unique IP Addresses Make Credential Stuffing Attempts on Daily Basis” — Auth0

“Using 14 days of data, we observed 21,962,978 login attempts; of those, 33% (7,379,074) represented failed logins.” – Akamai

Cashing In on an ATO

Cunningly mimicking the victims’ footprints and the patterns in their account while avoiding having the security and fraud safeguards invoked in a successful credential stuffing attack, criminals amass critical account information that they can opt to consume in different ways to help achieve ATO.

They could be the sole owner of the account to impede other criminals’ accessibility by changing the victim’s credentials; ergo, locking the victim out of his own account. Nonetheless, by keeping the credentials as is, the criminal may act as the temporary co-owner of the account, while familiarizing himself with the victim via DSR exploits and preparing a reliable pretext for a strike. At the end of the nesting period, in other words, once the account is “mature” enough with proper gathered authorizations and verifications to make high-risk actions from the owner of the account, the criminal exploits this information by increasing the victims’ credit card limits or extending their credit line, taking unsecured loans and making wire transfers and ACH payments. Ironically, the nesting period brings with it the risks of being targeted by rival criminals and losing the ATO all together, along with the time and resources invested.

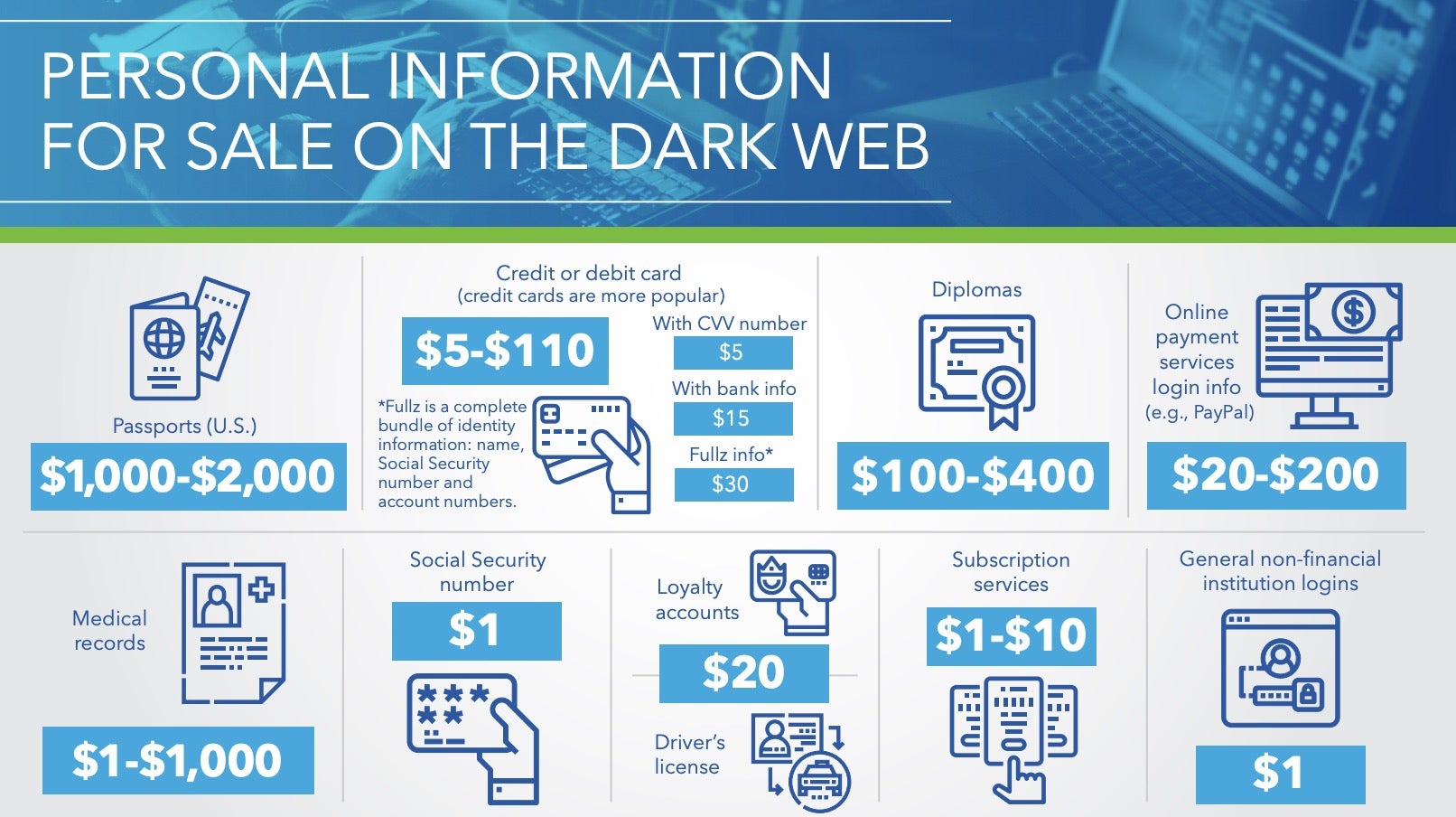

Last but not least is the utilization of the ATO to act as a mule account for different purposes, such as money drop to serve as a redirector/bouncing account that gets the account holder up to 20% commission. The commission charges change if the money mule is managed by a money herder to attract more drops. And of course, there is also the option in some cases to hold the account as ransom or just sell the account credentials (aka “log”) with full collected information of the victim (aka fullz).

“The bank usernames and passwords are not as important as the fullz and here is why. With a bank username and password by itself you can’t do very much, but with fullz records you can CREATE NEW bank usernames and passwords that will match whatever IP/Browser Agent you are using. So think of the fullz as the master key to fraud…With all this info you can do each transfers of 10k or more, open brand new 15,000 USD and up credit cards, open up fresh bank accounts for quick internal transfers, and way more…” — Cybercriminal explaining

ATO Pricing and Selling

Prior to monetizing an ATO, deep evaluation of the account characteristics – account balance, victim’s age, confirmed payments, victim’s financial history such as credit score and other aggregated transaction information – is conducted by the criminals to determine the overall worth of the account.

With the development and adoption of predictive algorithms (e.g., criminal FICO), account pricing is complex and tricky because account credentials are packaged with equally complex-to-price digital doppelgangers and require proxies associated with the given account credentials. Therefore, considering the diversity of the types of accounts (loyalty and rewards, OTT, digital intangibles, financial accounts, etc) and their idiosyncratic characteristics, it is crucial for the criminals to meticulously calculate the tag price of the accounts.

Selling credentials can be done in a variety of ways. One way, which often requires a commissioned escrow service (e.g., middleman services), is transacting with a broker who provides credentials on-demand or as a subscription service. Thereupon, the broker provides his fellow criminal subscribers with updated credential combo lists regularly for a periodic fee. Having the escrow as an intermediary not only ensures the security of the money transfer between the criminals but also the functionality of the provided credentials. Furthermore, they also provide additional services like sorting information that was dumped from ransomware stealers to fetch the relevant credentials and verifying the quality of data prior to the transactions with brokers.

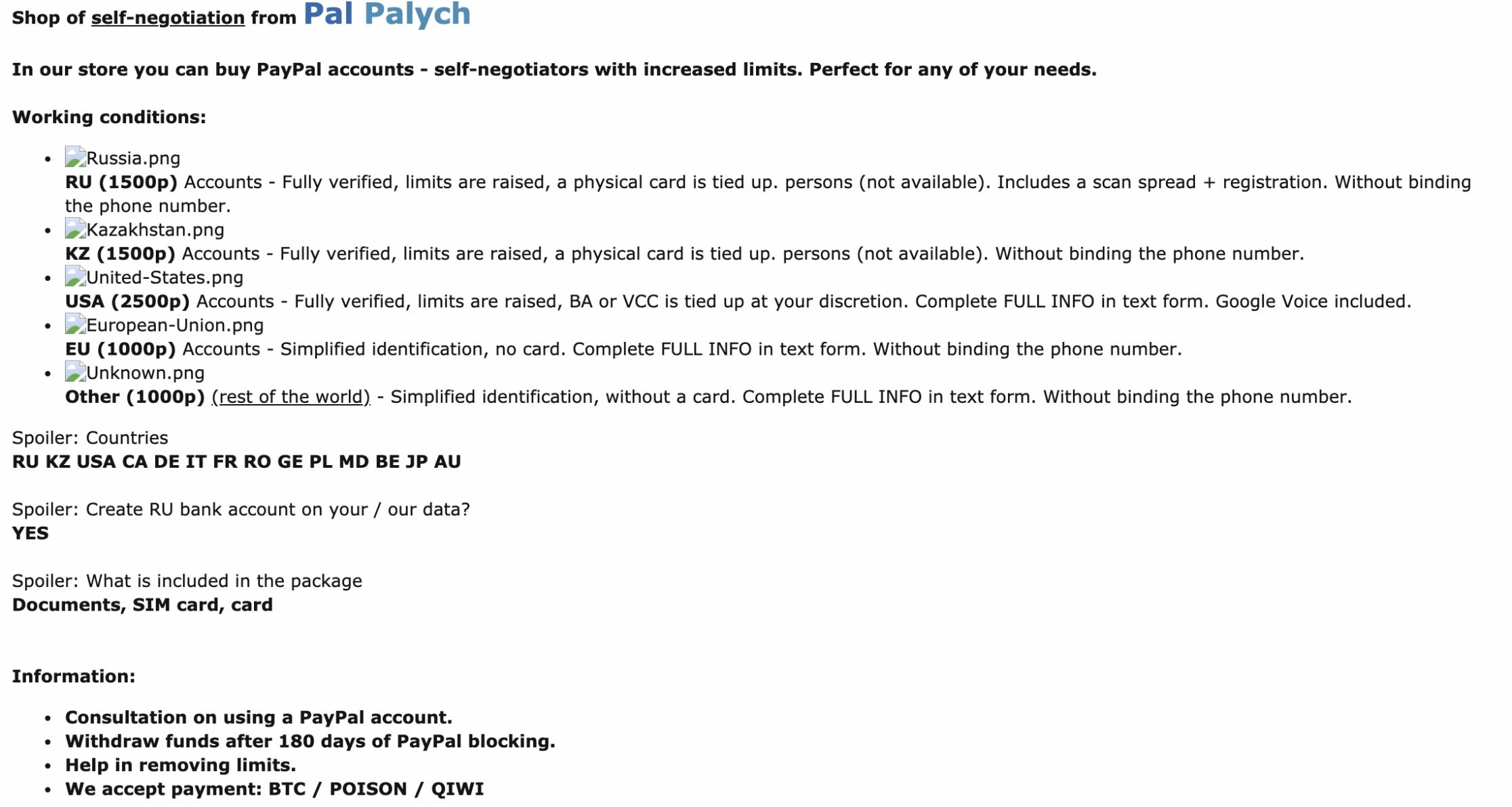

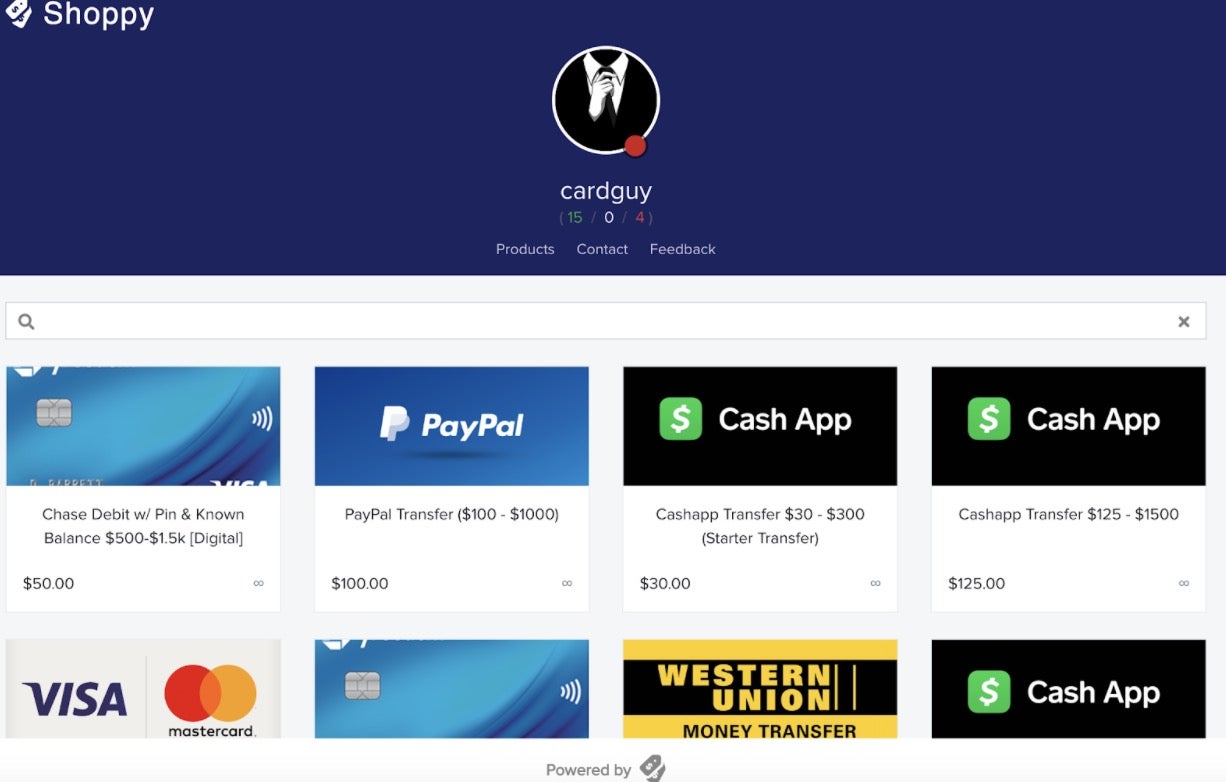

Additionally, platforms like Telegram – as well as dedicated “Account Shop” marketplaces with professional customer service providing quality assurance against defective batches for a commission of 10-15% of the asking price – serve as facilitators for the criminals. Another option is selling via the digital intangible storefronts i.e Shoppy, Selly, Deer.io for a minimal monthly cost of $11. Some storefront platforms can even be embedded directly within the very visible surface web forums (e.g., RaidForums, Ogusers, Cracked) with very easy to use payment gateways and integrated crypto-wallets using privacy coins (e.g., Monero), BTC or other payments processors (e.g., PayPal and others).

“Many accounts compromised via credential stuffing will sell for as little as $3.25 USD. These accounts come with a warranty: If the credentials don’t work once sold, they can be replaced at no cost” — Akamai, 2019

Cashing Out

In order to cash out the funds deposited into their drop accounts, criminals need to be equipped with an understanding of regional and international legal, regulatory and operational measures set to combat money laundering and other related threats.

For instance, with the introduction of the PATRIOT Act, compliance with the AML/KYC regulations has been extended beyond financial institutions to standard citizens consuming financial services. It serves as the de facto counterproductive measure as the personal KYC data can be traded and used for identity theft in event of a breach.

Despite the prior existence of KYC/AML regulations, attacks on U.S. soil gave the government a pretext to implement the PATRIOT act. Terrorism funding was the underlying reason that governments gave for tracking the trail of money moving throughout the world.

Even if criminals follow the restrictions (i.e., avoiding transactions above $10,000), they still run the risk of a suspicious activity report (SAR) that can challenge the cashing out process. However, experience criminals, and especially organized cyber gangs, have the resources and specialists with expert understanding of payment infrastructure and can devise a vigilant cashing out strategy to avoid any hindrances that may tamper with withdrawal.

Supplementary Services for ATOs

Having described the end-to-end process from credential stuffing to cashing out, it is worth covering some of the additional capabilities of bad bots that supplement the cybercrime business, especially when the compromised accounts are “burned”, prompting criminals to shift to “Plan B”.

Due to the imperative of time-consuming efforts to reopen accounts and reload the content, criminals need to lay down the groundwork in advance in order to swiftly shift to ‘Plan B’ without raising any security flags.

Prior to opening a new account, criminals need to have the synthetic identities (aka Frankenstein IDs and ghost profiles) and digital twins backed with original data assembled in addition to the forged hard and soft documents to satisfy KYC and/or identity-proofing processes to establish the legitimacy of the pseudo account.

Even so, successful account creation is only the preliminary stage for the criminals as subsequently they need to initiate the process of ‘aging’ the account. “Aging” an account refers to creating a sense of maturity of an active account by usually creating false transactions and activity, while mimicking human behavioral patterns to avert being flagged for potential fraud. Such preparations usually require relatively complex automation techniques. For example, in some cases criminals will need to create other providers’ accounts to get a new VCC (virtual credit card) or accounts in neobanks for account validation and verification purposes. It’s worth noting that there are a multitude of supplementary and complementary services (proxies, accounts, and servers) as well as facilitators providing special services to aid criminals specifically for creating synthetic business accounts and to establish a presence (i.e website, forms of payment, and mail drops).

The hacker who allegedly cracks PayPal accounts says that while he’s been banned “quite a few times,” he’s able to boot up his storefront with a temporary email address and a new username in “five minutes.” — Luke Winkie

In a constantly growing industry of bad bots, the scale of operations extends beyond ATOs and validity checks to providing on-demand services, sales bolstering, post review improvement services and many other types of ad-fraud (forecasted to earn $29 billion by 2021). Moreover, bad bot centers enable a solid proxy ground for account setup, management, and control of those in different platforms for mass scams like scalping and copping while creating a barricade against shutdowns.

Of the industries with a major prevalence of mass adoption of credential stuffing powered by bad bot services are travel, retail, the entertainment industry, and social media. For monetization in social media, criminals strive to compromise high-profile accounts of “legitimized” influencers, officials and celebrities and thought leaders through ‘wetware’ exploitation to inflate the price of cryptocurrencies, amplification pump and dump stock schemes, cognitive mind hacks, trust-trading scams, promotion copycat and fake apps or crafted phishing links enabling mass ATO.

An auxiliary income stream of bots for criminals can be observed in the publicly consumed on-demand service industry. With the public seeking to enhance a sense of authenticity via social proofing (including social verification and validation) of sockpuppet, impostor, cyborg, “doubleswitched” accounts as well as influencer accounts (costing an estimate of $1.3 billion), the demand for service providers of undetectable toxic user-generated content (UGC), fabricated followers, likes, reviews, and comments is on the rise.

These activities, which originated from account control centers (i.e troll farms and click farms utilizing physical devices and device emulators), depict the pervasiveness of the use of bad bots as a service. Bizarrely, it even extends beyond online to public places such as automated vending machines that sell Instagram and Vkontakte likes and followers (50 rubles / ±$0.9 per 100 likes).

“Facebook has been lying to the public about the scale of its problem with fake accounts, which likely exceed 50% of its network.” — PlainSite Report

“Spending 300 EUR, we bought 3,530 comments, 25,750 likes, 20,000 views, and 5,100 followers” – NATO

Cross-Account ATOs

Rising adoption by businesses of delegated authentication services (e.g., “Log in with Twitter”) to provide users with a smoother authentication experience without the hurdle of creating new registrations also serves as a facilitator for credential stuffing. Bearing in mind the user tendency of interlinking different platform accounts (e.g.cross platform login), once the criminal attains the ATO of one of the interlinked accounts, cross-ATO of the remaining accounts through the compromised one becomes straightforward.

This phenomenon presents a greater threat with the rising adoption of “all accounts in one place” aggregators, which use different connection methods, assistant applications, and open banking through third-party trusted companies such as Fintechs. Such companies have disparate customer data protection approaches and typically lack the stringent standards and regulations that banks are subjected to, which only widens the attack surface for criminals.

Criminals are thus presented with an open playground to conduct sophisticated, second layer credential stuffing attacks such as via a compromised account in the main superapp, which facilitates accessibility to integrated third-party service applications (e.g., in-app web-applications and mini-programs).

The increasing prevalence of daily platforms such as gaming, social, and communication apps with integrated third party services prompts criminals to seek novel attack techniques. Considering “everything commerce”, revenue diversification strategies companies lead new business opportunities without adopting a unified omnichannel authentication approach throughout all of their cross-channel logins, and in the process serve up persistent, lucrative avenues for criminals.

Finally, let us note that studies have also shown technology advances make it possible to create even smarter credential stuffing attacks, one of which discusses a credential tweaking attack with a success rate of 16% of ATOs in less than 1000 guesses using deep learning techniques.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Having discussed the end-to-end process of automated ATO attacks in a thriving industry of cybercrime, as well as the repercussions of the attacks on businesses and public, we should consider the following measures to address the issue.

Tailored MFA

It is crucial to tailor user authentication experience as a continuous process with fit-for-purpose authentication factors to combat ATO attacks. Therefore, to provide clients with the ultimate frictionless experience throughout the user journey, we should weigh the pros and cons of different structures and how to combine the three types of MFAs in a continuous and adaptive authentication process. Optimizing the MFA structure requires a focus on prioritizing UX, while minimizing the security risks, and adopting a structure fit for the respective business flows and requirements.

It is essential to avoid similar MFA processes of other related businesses, imposed use of existing or common MFA solutions (e.g., biometric authentication) and default/assumption based authentication methods. These are not only cost ineffective but also lead into higher abandonment rates with users struggling to pass the authentication challenges.

While bearing in mind the pitfalls of the MFA methods, when adapted vigilantly per business needs and users profiles, they can present a barrier against robotic and manual attacks; rendering robots disoriented in their attempts to adopt the authentication structure and presenting a time-consuming challenge for the attackers.

However, MFA isn’t a foolproof obstruction against automated and targeted ATO attacks, considering the sophisticated detection evasion techniques some employ. This necessitates us to adopt a proactive approach (e.g., task-driven threat hunting) and establish collaboration amongst UI/UX developers, software engineers, and pentesters.

Further, we need to adopt deception techniques e.g., using previously used user credentials as honeytokens and/or distributing honey identities rather than relying heavily on non-human-session hindering solutions, lockout policies, and CAPTCHA type controls, which are overall futile endeavors and also can be counterproductive.

Prompting users to resort to self-service unlock procedures both redundantly burdens the SecOp analysts, diverting them from tackling what is crucial (alert fatigue conundrum) and increasing the staff overhead for the business, as well as detering the user and enabling criminals.

Use the Data

The favoritism towards the controversial “assume breach” mentality with a “when, not if” attitude to avert cyberattacks may obscure the focus on what is crucial. We should be cognizant of the potential gaps and threats through data-driven scrutinization of our existing deployed endpoint solutions to effectively mitigate those gaps and threats, while avoiding solely “gut feeling” oriented decision making.

In order to devise believable attack models and realistic views of our risk posture, embracing high-value threat data and intelligence-driven decision making, tailored for specific business objectives, is essential. Combined with a focused investment approach to implement enhanced interconnection across the security layers, this would enable us to acquire a bespoke understanding of what and why to prioritize, thus addressing the root causes of the threats.

User Awareness

As discussed in the article, one of the most critical catalysts of the automated ATO attacks is the users’ tendency to reuse passwords on different platform accounts. In order to increase users’ cybersecurity awareness, technology companies should strive to avoid bias in their published statements, surveys, and research reports. Implausible and deceptive statements such as “multi-factor authentication blocks 99.9% of account hacks” can be counterproductive when research and experience proves that not to be the case.

Similarly, encouraging the use of password managers, without creating awareness about the trade-offs of using them can harm adoption and confidence in the solution. Hence, it is essential to educate users how to use such technology effectively, and to emphasize the need to secure high-value accounts with sufficiently complex and unique passwords, as well as to help users adopt good security behavior like monitoring their accounts’ breach status via lookup services.