The Good

This week was full of cybersecurity news related to the war in Ukraine and Russian threat activity. While the ongoing conflict remains quite horrific, and at times difficult to find any “good” in, we can thank the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) for their work.

On Tuesday the 15th, SBU publicly announced the arrest of an individual supporting the Russian mobile communications network while in Ukraine, and the targeting of Ukraine Officers in an attempt to persuade them to surrender.

According to the Telegram post from the SBU, the individual has made up to a thousand calls facilitating the Russians’ communication. Russian leadership and fighters alike continue to communicate with unencrypted channels, such as VHF radios and mobile phones.

A review of the images released by SBU have been analyzed by various professionals, who highlighted the fact that this equipment should not have been used in a military environment being vulnerable to detection and tracking. In some cases, the reliance of Russian troops on the Ukrainian mobile network may have been caused by them destroying 3G towers, then forcing them to begin using unencrypted radios.

Taking all of this into account, it acts as a simple example of the importance of communication planning during coordinated engagements. The same could be said for defenders as well, including even those of network defenders and incident responders.

The Bad

There continues to be a large flow of bad news in the cyber domain this week, again particularly on the topic of the Ukraine conflict. As noted in our recent webinar, the amount of new intrusions, attacks, and the confusion of many of the actors behind them, can make it easy to miss the little events occurring which can impact businesses globally.

This week, SentinelOne published the identification of new UAC-0056 activity targeting Ukraine with fake translation software. The research attributed the activity to a cluster of UAC-0056 threat actor activity reported by UA-CERT in the days prior.

This malicious activity originated through a large program masquerading as Ukrainian language translation software, leading to the infection of GrimPlant and GraphSteel malware families. Interestingly, the research also identified that the threat actor began building the infrastructure around this campaign in at least December 2021 – earlier than previously known, and showcasing some pre-invasion preparation from the threat actor.

UAC-0056 is the threat actor title assigned by the Ukrainian CERT, while others in the industry have titled them UNC2589, TA47, and SaintBear to name a few. Current working knowledge is that this actor is either responsible for, or closely related, to the WhisperGate activity in early January 2022 impacting government agencies in Ukraine. As with all events occurring around the conflict, new details are expected to emerge and shift the understanding of many known events.

The Ugly

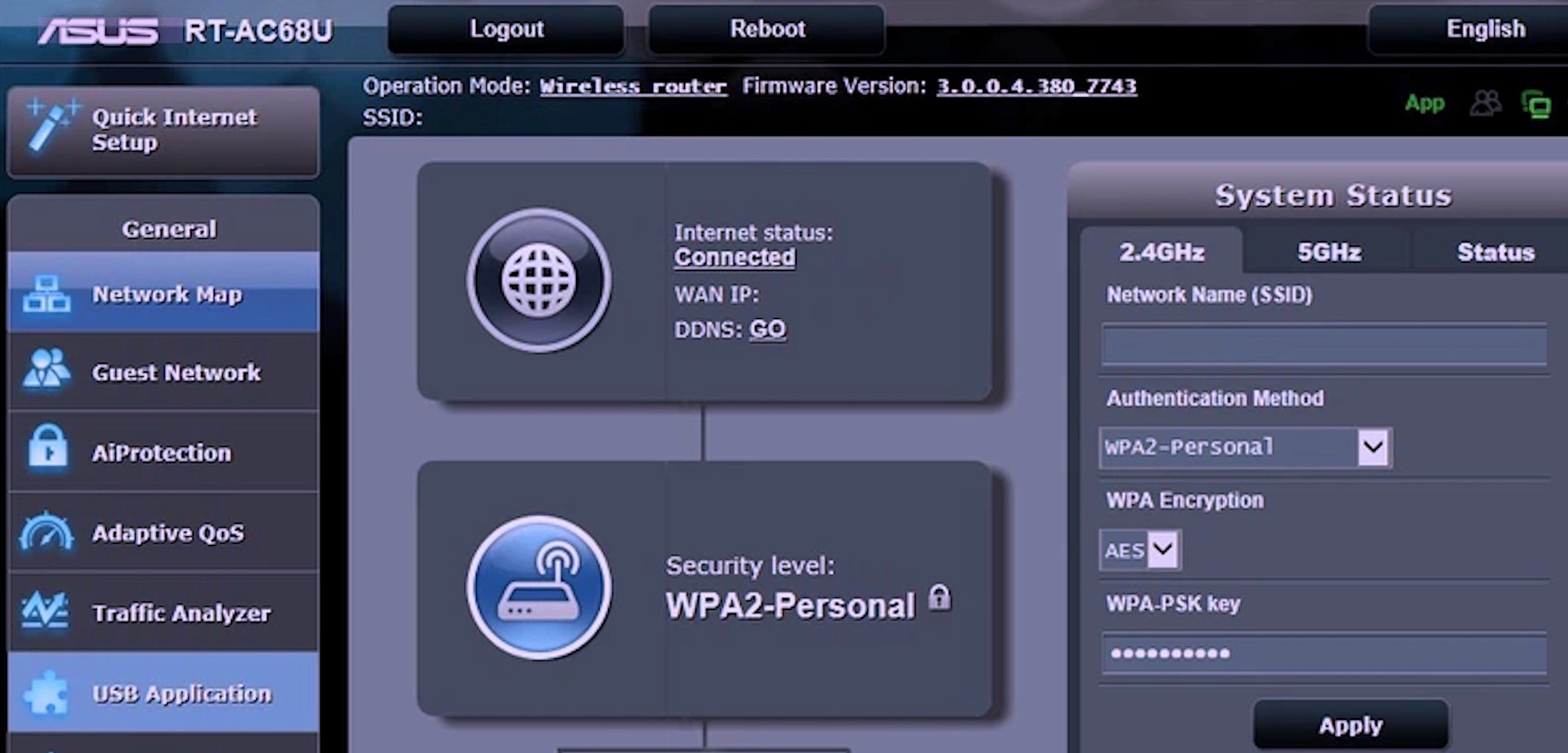

On a more ugly note this week, we have the identification of the Cyclops Blink malware impacting Asus routers and operating as a larger-than-known botnet for one of the most notorious destruction-fueled threat actors known – Sandworm. Additionally, the researchers observed evidence of at least two hundred victims in the US, Russia, Canada, and Italy.

As we reported previously, Cyclops Blink was found targeting WatchGuard Firebox network devices last month, but now researchers have discovered the malware targeting Asus and likely other home and small-business networking equipment manufacturers, too. The researchers note that the same code was used in attacks on Asus and WatchGuard boxes, and simply recompiled for the brand of interest.

Cyclops Blink can read and write from the router’s flash memory, which is used to store the operating system and configuration, among other files. It reads 80 bytes from the flash memory, writes that to the main pipe, and enters a loop to wait for a command to replace the partition content. The replacement is achieved by erasing the NAND eraseblocks and then writing the new content to them. Crucially, since the content of the flash memory is permanent, Cyclops Blink can use this method to establish persistence and survive factory resets.

Currently, the intent of Cyclops Blink remains unclear. However, IoT devices are increasingly a major target for attackers interested in all manner of cyber objectives, from DDoS to espionage. Cyclops Blink’s focus on home and small-office networks devices is particularly concerning as it suggests the operators are interested in casting a wide net and gaining victims at scale.