Last week, PinnacleOne examined the state of aviation cybersecurity given recent incidents and federal action.

This week, we boost our view into orbit and dive into the intersection of cybersecurity and geopolitical risk facing the rapidly expanding space economy.

Please subscribe to read future issues — and forward this newsletter to interested colleagues.

Contact us directly with any comments or questions: [email protected]

Insight Focus: Commercial Industry in Contested “Space”

In early April, the United States Space Force (USSF) released their first Commercial Space Strategy, embarking on a major shift in its approach to space operations, one that recognizes the pivotal role of the private sector in driving innovation. This USSF move to integrate commercial space solutions into “hybrid architectures” will raise critical issues of “dual-use capabilities” facing cyber and counterspace threats from China and Russia across peacetime, crisis, and conflict.

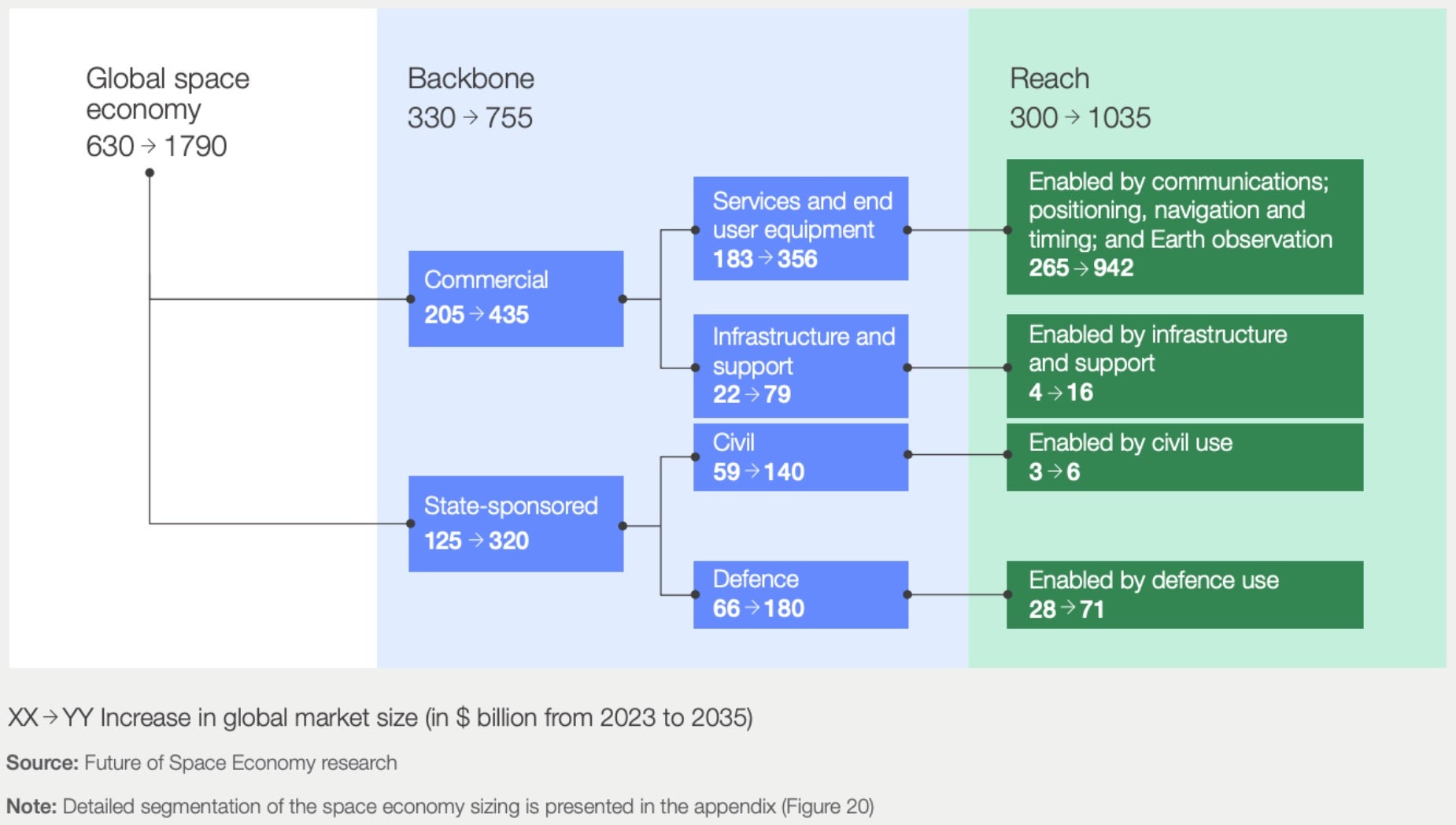

This strategic shift is not just about leveraging commercial space capabilities, but also about managing the inherent cyber and interdependent risks that come with relying on private sector systems. The specter of cyberattacks on commercial space systems, with the potential for cascading impacts on military operations and the broader economy, looms large in this equation, even as the space economy is projected to reach $1.8T in value in the next 10 years.

Rapid innovations like SpaceX’s Starlink and Starshield, and other advanced orbital systems servicing an emerging commercial space economy present a double-edged sword for the USSF:

- Opportunities to enhance capabilities and resilience in peacetime, while

- Ensuring security and interoperability in crisis or conflict.

Investments by the U.S. and China in intelligence, tactical, and strategic platforms will drive most of the state-directed activity, but commercial and scientific activity will also accelerate as more nations get into the space game. Just in the last decade, the United Arab Emirates, for example, created a space agency, put an astronaut on the International Space Station (as did Saudi Arabia), sent a probe to Mars, and is collaborating with NASA on the lunar Artemis program.

Security Implications of Dual-Use Commercial Space Capabilities

One of the most significant challenges lies in the inherent ambiguity of dual-use space tech: capabilities developed for benign purposes (e.g., on-orbit satellite rendezvous) could also be used for military operations (e.g., tactical recon in a crisis or offensive operations in conflict). This blurs the lines between commercial and military applications and creates legal and ethical quandaries in a fast growing strategic industry mixed with large legacy government contractors and “deep tech” commercial startups desperate for product-market fit and sustainable business models.

The evolving risks in the space domain, starkly illustrated by Russia’s nuclear ASAT system and China’s growing space capabilities, underscore the paramount importance of robust Space Domain Awareness (SDA) and resilient architectures that give the U.S. warfighter an advantage in a contested environment. Chinese or Russian cyberattacks on US commercial satellites could disrupt military operations in crisis or conflict, with broad-scale and cascading commercial and economic effects on the ground.

The USSF’s approach to hardening immature startups is key, given the latter’s tight budget constraints and financial imperative to grow first, secure later. Space assets are of high value (to both their owners, customers, AND their attackers) but are deployed by businesses that require high capital investment and run on thin margins. This combination presents a real problem for DoD’s Commercial Space Strategy. This issue is of critical importance not only to firms in the space industry but also to those in cybersecurity and the vast array of businesses and sectors that depend on both – which, in today’s interconnected world, is essentially everyone.

The DoD has had ongoing challenges rolling out updated cybersecurity requirements for contractors, announcing plans for a revised “Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification 2.0” program more than two years after it delayed an initial CMMC rule in late 2020. It may finally finalize the rule by the end of 2024 and requirements will waterfall down to all defense contractors soon after. Meanwhile, the USSF has already pushed out cybersecurity requirements that go beyond what CMMC requires, so space force contractors will have to comply with both.

Crisis and Conflict in Space

In a conflict scenario, the risk of kinetic or cyber attacks on U.S. commercial satellites is magnified. Balancing risk-sharing between USSF and the industry in peacetime is critical for resilience in war, as is the expectation setting for reciprocity, indemnification, and restitution.

In fact, the Space Force expected to begin identifying members of its newly formed Commercial Augmentation Space Reserve (CASR) by 2025 (the equivalent of DoD’s Civil Reserve Air Fleet for aviation and the Maritime Administration’s National Defense Reserve Fleet), focusing on space domain awareness, satellite communications and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance.

However, a critical distinction from the aviation and maritime domains is that, in the space domain, the second it’s known that a commercial platform is supporting a military mission, they become a target. Even membership of such a Reserve program will likely raise the risk profile for participating firms, given the pervasiveness of the threat environment in space. For example, PinnacleOne has advised participants in the CRAF that they are likely a target of Chinese military hacking groups tasked with executing disruptive or destructive attacks in a crisis or conflict.

The Space Force is moving quickly to embed strong contractual requirements for cybersecurity and operational reliability, but has yet to issue a formal construct for sharing relevant threat information with CASR members. Also, it is an open question if and how US Space Command (SPACECOM) would protect and defend commercial space assets if attacked.

Commercial Risk Management in Space

The USSF’s strategic principles provide a guiding framework for its peacetime efforts:

- Balance

- Interoperability

- Resilience

- Responsibility

However, significant obstacles remain in the face of near-peer competitor threats that could emerge in a crisis. The ambiguity of crisis conditions will stretch gaps in existing doctrine and operational collaboration. The lines of effort outlined in the strategy serve as important signposts in peacetime:

- Transparency

- Integration

- Risk management

- Securing the future

The true test, though, will come in addressing the counterspace and cyber capabilities of China and Russia in a conflict scenario, particularly for priority missions. This is already a challenge in terrestrial cyber operational collaboration between the public and private sectors, with issues relating to information sharing, overclassification, and tactical coordination and deconfliction.

The USSF faces a daunting challenge in leveraging commercial technologies in peacetime while managing the risks inherent in relying on private systems in a contested domain during conflict. Wargaming exercises that integrate commercial partners and red team simulations – at both the level of operational/tactical peers and government and enterprise leadership – will be vital in preparing for these eventualities.

A Strategic Shift

The shift to a model of consuming commercial solutions represents a seismic philosophical change for the USSF, given its history of using legacy primes developing cost-plus platforms “behind the Green Door” of special access program secrecy. Navigating the complexities of great power competition in peacetime while mitigating the risks of over-dependence on potentially vulnerable systems in conflict will require a delicate balancing act.

The integration of commercial solutions into hybrid architectures offers the promise of enhanced resilience in peacetime. However, it also expands the potential attack surface in a crisis or conflict scenario. The USSF’s approach to setting robust cybersecurity standards and collaborating closely with commercial partners to secure networks will be critical to managing these risks.

Ultimately, the success of the USSF Commercial Space Strategy will hinge on the ability to artfully manage the intricacies of commercial-military integration in peacetime while being prepared to counter the multi-dimensional threats posed by China and Russia in a crisis or conflict situation. The stakes could not be higher, as the outcome will have far-reaching implications for U.S. space superiority in an increasingly contested domain.

High Risk, High Reward

As the USSF navigates this uncharted territory, it will need to be agile, adaptive, and proactive in its approach. Balancing the imperatives of leveraging commercial innovation, ensuring security and resilience, and maintaining a decisive edge over near-peer competitors will require a level of strategic finesse unprecedented in the history of military space operations.

The Commercial Space Strategy represents a bold vision for the future of the USSF. Its success will depend on the ability to harness the immense potential of the private sector while mitigating the inherent risks and challenges. As the USSF embarks on this journey, it will need to be guided by a clear-eyed understanding of the strategic landscape and an unwavering commitment to maintaining U.S. space superiority in the face of an uncertain and contested future.