Executive Summary

- SentinelLABS identified 10+ patents for highly intrusive forensics and data collection technologies that were registered by companies named in U.S. indictments as working on behalf of the Hafnium threat actor group.

- These technologies offer strong, often previously unreported offensive capabilities, from acquisition of encrypted endpoint data, mobile forensics, to collecting traffic from network devices.

- Our research explores the relationships between indicted hackers, ownership of the firms they are associated with, and the relationships those firms have with several government entities who conduct offensive cyber operations on behalf of China.

Overview

In July 2025, the Department of Justice (DOJ) released an indictment of two hackers, Xu Zewei and Zhang Yu, working on behalf of China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) that sheds new light on the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) contracting ecosystem. The indictment outlined that Xu and Zhang worked for two firms previously unattributed in the public domain to the Hafnium (aka Silk Typhoon) threat actor group. Hafnium has a long history of attacks against defense contractors, policy think tanks, higher education, and infectious disease research institutions, with an exceptionally prolific 2021 campaign that exploited several 0-day vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange Server (MES). Hafnium’s history of exploits and 0day use, combined with its targets and observed campaigns make it one of China’s best APTs.

This research resulted in three key findings.

- We identified previously unobserved or unreported offensive tooling owned by Hafnium-associated companies named in U.S. indictments. The tooling raises questions about these firms’ on-going work in support of the MSS and how attribution is difficult. The company holds at least one patent on software designed to remotely recover files from Apple computers, which has not been documented as a capability used by Hafnium or any related threat actor groups.

- The DOJ indictment provides new insights into the tiers of relationships between hackers and their customers. This report raises important questions about the extent to which the MSS and its regional offices offer operational support to its contracted hackers.

- Our research delves into several companies tied to the indicted Hafnium-affiliated hackers and documents their relationships. Importantly, the report finds evidence of multiple companies registered by one of the defendants, and dozens more by an associate.

This new insight into the Hafnium-affiliated firms’ capabilities highlights an important deficiency in the threat actor attribution space: threat actor tracking typically links campaigns and clusters of activity to a named actor. Our research demonstrates the strength in identifying not only the individuals behind attacks, but the companies they work for, the capabilities those companies have, and how those capabilities fortify the initiatives of the state entities who contract with these firms.

Hafnium’s Impact

It’s rare for a hacking team to behave so recklessly that it changes a country’s foreign policy and unify the E.U., U.K., and U.S. into speaking with one voice, but Hafnium wouldn’t be famous if they hadn’t done that. And, actually, they didn’t do it.

Hafnium gained fame following the revelation of their stealthy access to U.S. Government emails through an MES vulnerability known as ProxyLogon, which came to light in March 2021. But the group is often wrongly blamed for what happened next. The name Hafnium became associated with the wider abuse of the ProxyLogon vulnerabilities that followed the original Hafnium activity as lesser tier threat groups flooded the zone with exploitation attempts to opportunistically deliver payloads ranging from espionage to ransomware.

Microsoft alerted its Microsoft Advanced Protection Program partners to some POC code on February 23. This program provides some select cybersecurity companies early access to powerful new exploits, so they can better defend their customers. Five days later on February 28th, new Chinese state-affiliated and criminal hacking groups began exploiting the vulnerability at an immense scale. It remains unclear how exactly the exploit proliferated ahead of the patch. The longer tail of the problem arises from the prevalence of webshells littered by each attacker’s use of ProxyLogon. These groups left shells on vulnerable servers allowing access to these servers even after the vulnerability itself was patched. The situation was so dire that the DOJ received its first court authorization for the FBI to remove these shells en masse from compromised servers.

The rapid dissemination and exploitation of the vulnerability led the U.S., U.K., and E.U. to issue their first ever joint statement condemning PRC actions in cyberspace in July 2021. The statement roiled CCP policymakers who had previously fended off such joint decrees by convincing one E.U. state to reject such declarations. Because the E.U. requires unanimous consent for foreign policy statements, the fallout from the wanton abuse of the vulnerability upended China’s foreign policy success.

The joint statement so perturbed CCP policymakers that the country launched an offensive public opinion campaign against U.S. hacking operations that continues today. Before the July 2021 joint statement, the PRC did not coordinate cyber threat intelligence publications with state propaganda outlets. Following the statement, a pattern emerged of coordinated private-sector CTI reports, English-language propaganda pieces, and statements by the PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs. SentinelOne published a report detailing this change in February 2024 and the findings of that report are corroborated by a textbook on cybersecurity published by a committee of experts in China. China now regularly releases propaganda pieces alongside cyber threat intelligence reports–the change was completely prompted by the success the U.S. had in unifying the European Union behind a joint statement, which was itself enabled by China’s behavior.

Hafnium’s False Start or The Less Capable Cluster?

Following an intrusion into U.S. Treasury systems that came to light in late 2024, the Department sanctioned one of its alleged hackers, Yin Kecheng (尹可成). The Treasury sanctions announced in January 2025 were quickly followed by a March DOJ indictment of Yin and a business associate, Zhou Shuai (周帅). Two separate indictments were released for Yin in March. The first document is dated 2017 and only Yin is named as the defendant. The second indictment is dated 2023 and lists both Yin and Zhou.

Zhou Shuai, aka Coldface, is a first-generation patriotic hacker from China with a storied history of corporate registrations and work for the state. The March 2025 indictment of Zhou and Yin indicate that Zhou brokered the sale of Yin’s work through iSoon, a company whose internal chats and corporate records were leaked online in early 2024. Leaked chats showed iSoon executives considering a merger and acquisition of Zhou’s Shanghai-based company. iSoon executives also chastised Zhou for being a mere broker.

The DOJ press release for the indictments indicate that Yin’s and Zhou’s activities were tracked under various naming conventions and clusters, including Silk Typhoon. Microsoft updated the group’s alias from Hafnium to Silk Typhoon in 2022.

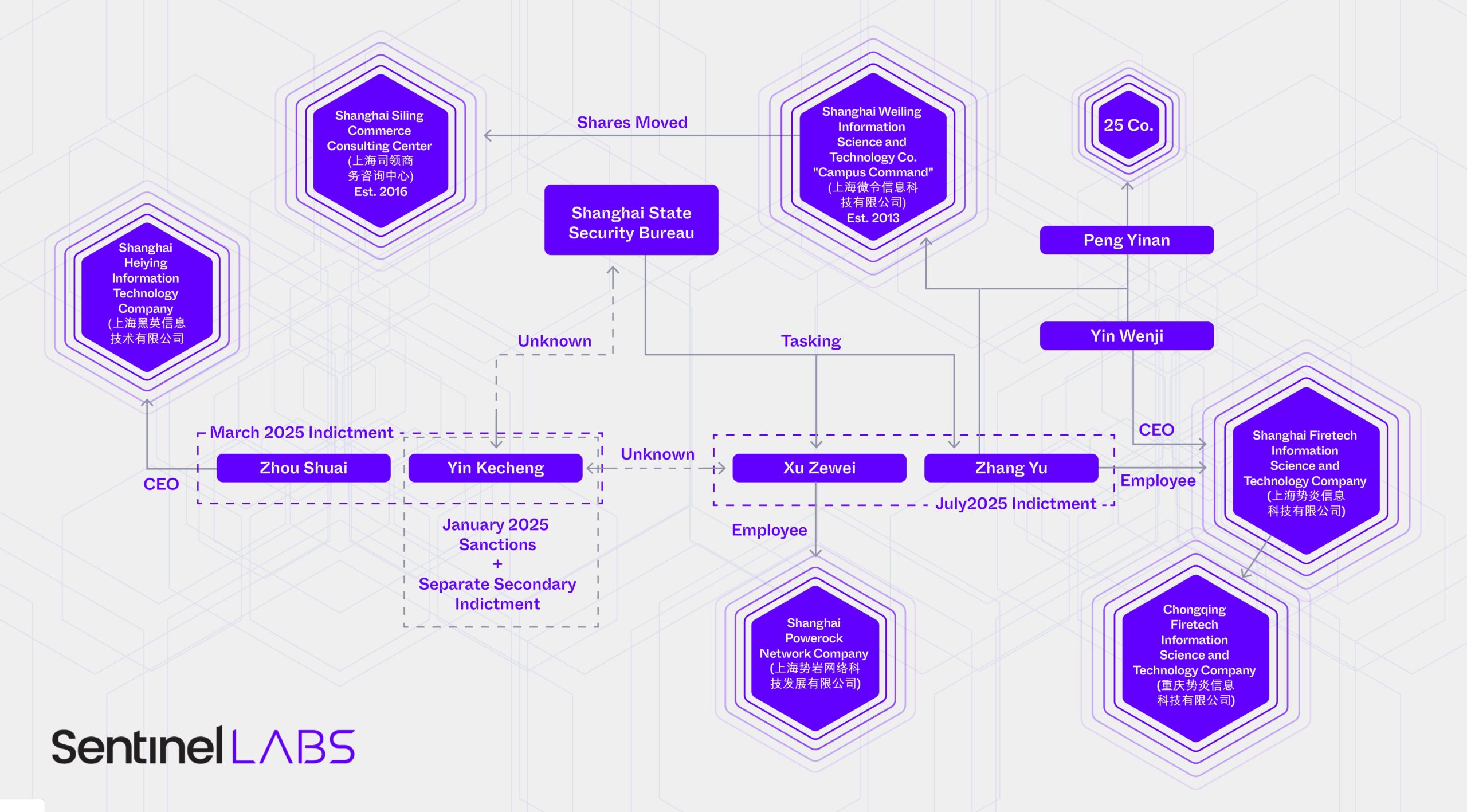

As of March 2025, Hafnium apparently consisted of a Shanghai-based company, Shanghai Heiying Information Technology Company (上海黑英信息技术有限公司), run by Zhou Shuai, which collaborated with Yin Kecheng in some fashion.

Hafnium and Other Elements

Following the July 2025 released indictment of Xu Zewei and Zhang Yu, the number of people alleged to work for Hafnium grew to four and the number of companies involved grew to three. The DOJ maintains that Xu Zewei and Zhang Yu worked at the “direction” of Shanghai State Security Bureau (SSSB). Xu Zewei completed his tasking while working at Shanghai Powerock Network Company (上海势岩网络科技发展有限公司); Zhang Yu worked at Shanghai Firetech Information Science and Technology Company (上海势炎信息科技有限公司).

This “directed” nature of the relationship between the SSSB and these two companies contours the tiered system of offensive hacking outfits in China.

Other capable analysts adeptly delve into Shanghai Powerock, so this report focuses on Zhang Yu’s company, Shanghai Firetech. Far from being an offensive shop procuring initial access and intelligence in the hopes of finding a willing buyer, as in the case of i-Soon, Shanghai Firetech worked on specific tasking handed down from MSS officers. The indictment maintains that Zhang Yu “supervised hacking activity, including that of other Firetech personnel in support of such [SSSB] taskings, and coordinated hacking activities with fellow hacker XU.” This indicates that Shanghai Firetech and co-conspirators earned an on-going, trusting relationship with the MSS’s premier regional office, the SSSB.

China experts and law enforcement distinguish between China’s operational structures. At the lowest tier of the contracting ecosystem are bottom feeders, like i-Soon. That company’s leaked files and U.S. indictment of their employees show a firm stuck in low-paying contracts with poor morale, and often subcontracting to bigger, better firms. A step up from i-Soon might be its prime contractor and competitor, Chengdu404, whose founders were also indicted. Chengdu 404 has stable business, works from multiple offices, and at one point was China’s most prolific APT. The tier of contractors the Chinese government holds closest are actors like Xu Zewei and Zhang Yu. But the MSS has not completely abandoned state-run operations. Past DOJ indictments show that other MSS offices do indeed use front companies. The Hubei State Security Department established Wuhan Xiao Rui Zhi (Wuhan XRZ) in 2010 as a front company for state operations.

You’re My Favorite Deputy

The peculiarities of Hafnium’s MES exploitation campaign raise questions about the relationship between the SSSB and its contractors. Hafnium began exploiting MES vulnerabilities beginning in January 2021. The exact date Hafnium’s campaign began is unclear, but the month is itself enough to raise eyebrows. On January 5, 2021, OrangeTsai tweeted he had found an incredibly powerful pre-auth RCE vulnerability, later confirmed to be the same MES vulnerabilities exploited by Hafnium. How did Hafnium come to exploit those vulnerabilities in the same month that OrangeTsai found them?

Theories swirled that Hafnium had compromised devices of employees working on inbound vulnerability reports at Microsoft. Other attention turned to the researcher’s personal security. As a resident of Taiwan, international conference attendee, and among the most talented vulnerability researchers with a public persona, it would not be inconceivable that Hafnium had itself hacked into OrangeTsai’s devices and stolen the vulnerabilities during his research phase.

But the Zhang and Xu’s close relationship with the SSSB raises the possibility that the Bureau collected OrangeTsai’s research themselves, either through an insider at Microsoft, a close-access operation against OrangeTsai, or some other collection method, and then passed the vulnerabilities to Xu and Zhang. A DOJ indictment shows the Guangdong State Security Department passing malware to its contracted hackers: had the SSSB done something similar?

Before Shanghai

How Zhang Yu and Shanghai Firetech came to work for the SSSB remains unclear. Before moving into offensive hacking, Zhang Yu co-founded a company Shanghai Weiling Information Science and Technology Co. (上海微令信息科技有限公司) whose smartphone application Campus Command (校园司令) aimed to connect college students with local events and information at Universities across China. But, as with all investigations, that is perhaps not the whole story. Zhang Yu co-founded Campus Command with the CEO and legal representative of Shanghai Firetech, Yin Wenji (尹文基). The two associated were joined by a third person, Peng Yinan (彭一楠). Campus Command was, until 2016, a subsidiary of Xin Kai Pu (新开普), a company whose shares are publicly traded on the stock exchange in Shenzhen. When Xin Kai Pu divested its shares, Peng, Yin, and Zhang moved their holdings into a privately held company offering business consulting services Shanghai Siling Commerce Consulting Center (上海司领商务咨询中心). Peng now holds shares in at least 25 companies registered in China.

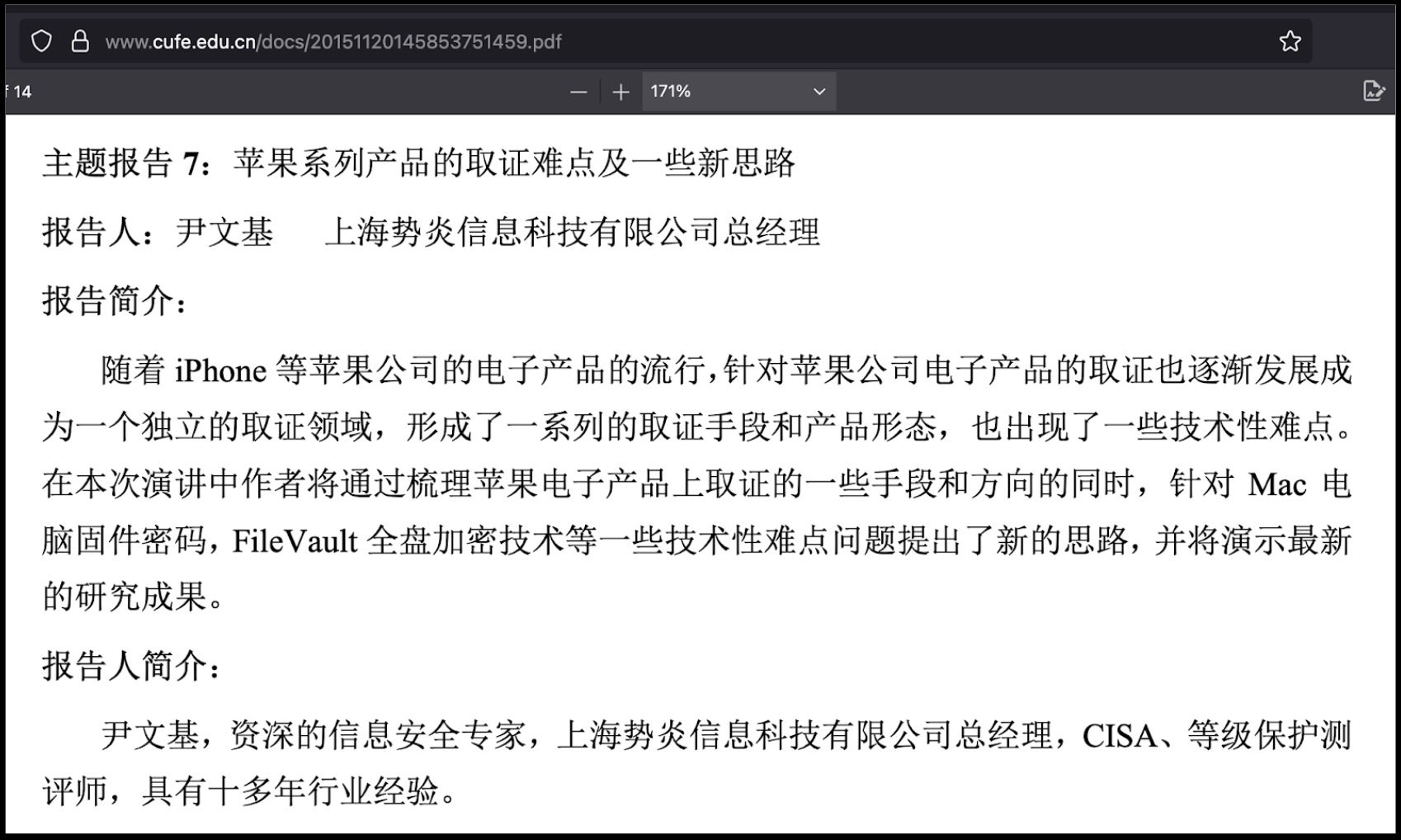

A 2015 talk by Yin Wenji, the eventual founder of Shanghai Firetech and co-founder of Campus Command, raises questions about his offensive capabilities while working at the university-focused company with the indicted Zhang Yu.

Yin spoke at the Central University of Finance and Economics program for cybersecurity. His 2015 talk advertised his ability to recover files from Apple Filevault five years before his new company would file for patent protection on a tool capable of collecting files from Apple computers.

The talk description translates to:

“In this speech, the author will sort out some methods and directions of forensics on Apple electronic products, and propose new ideas for some technical difficulties such as Mac computer firmware passwords and FileVault full disk encryption technology, and will demonstrate the latest research results.”

Silk Bandolier

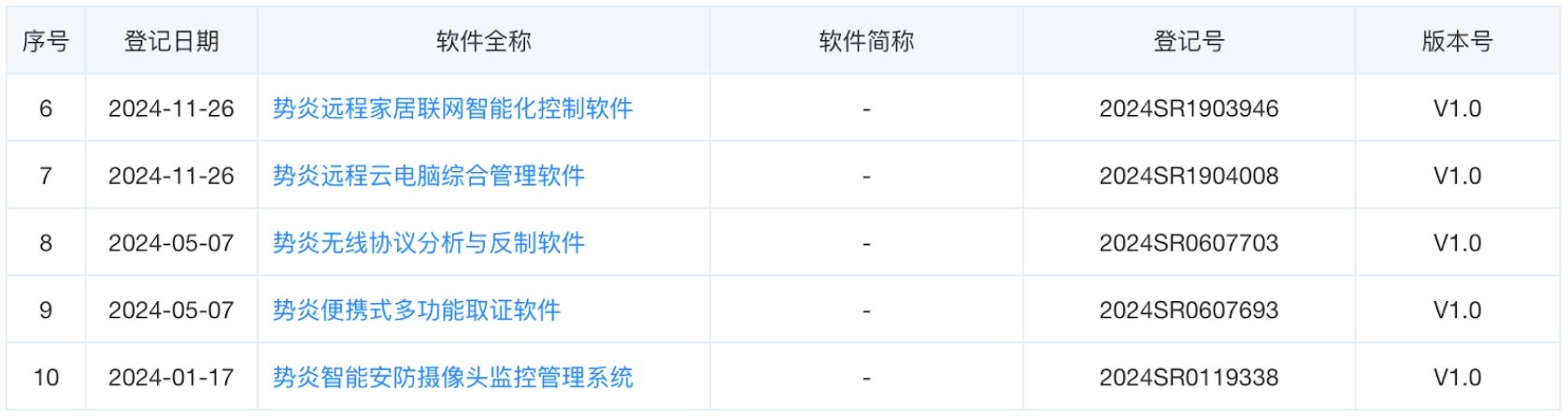

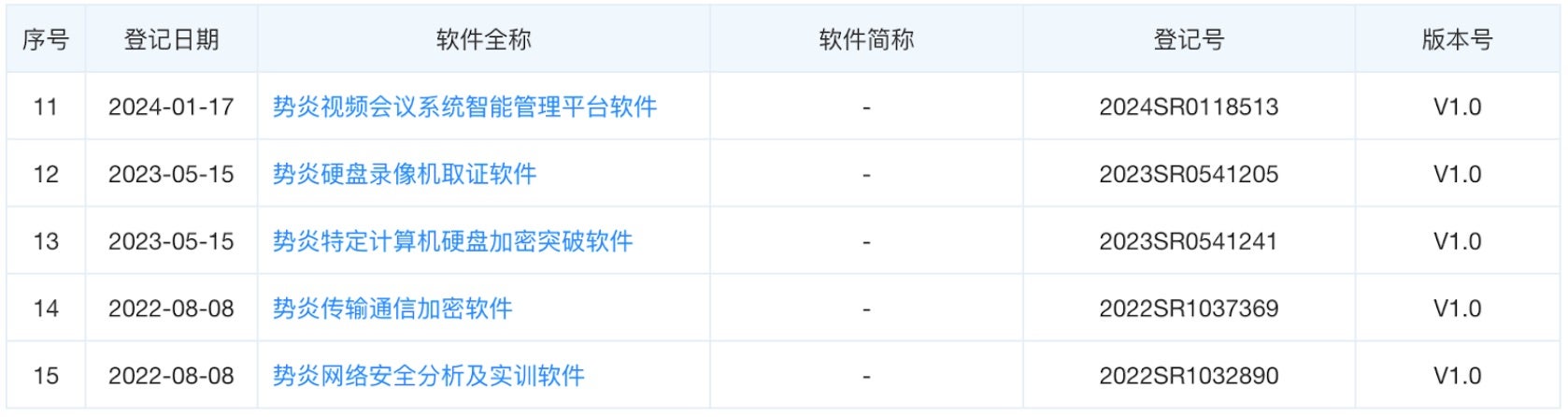

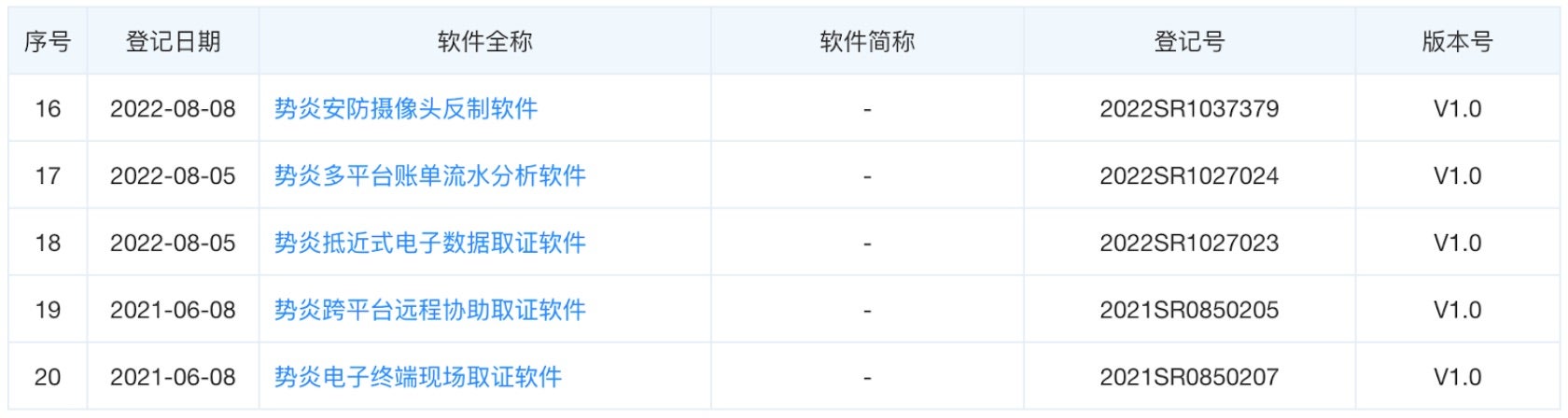

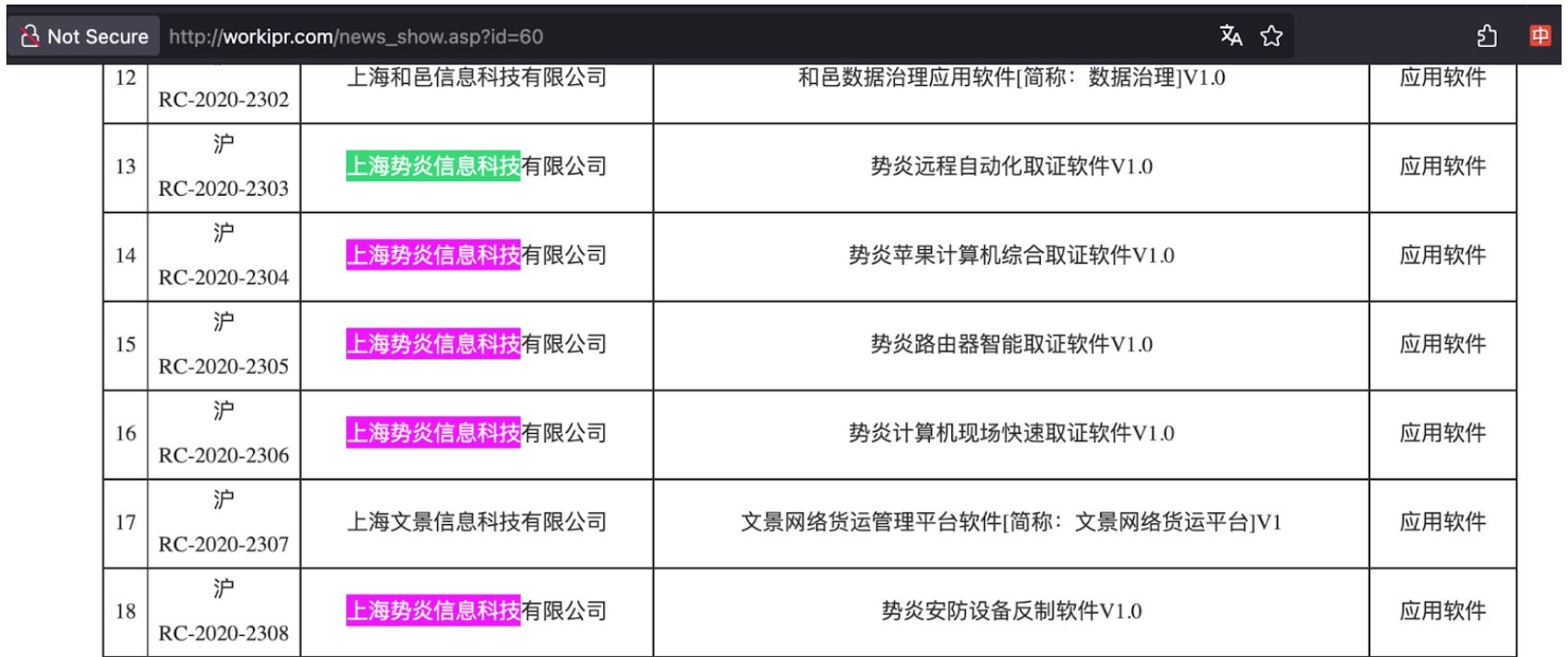

There is good reason to believe only some of Shanghai Firetech’s activities have been uncovered or made public by defenders. Hafnium rose to prominence in 2021 following the exploitation of four 0-day vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange Servers. Subsequent publications demonstrate the group is responsible for cracking a host of firewalls and network appliances. Intellectual property rights filings by Shanghai Firetech indicate an arsenal of tools not publicly attributed to Hafnium thus far. Shanghai Firetech filed for patents on a number of forensics technologies with clear applications as offensive capabilities including

- “remote automated evidence collection software”

- “Apple computer comprehensive evidence collection software”

- “router intelligent evidence collection software”

- “computer scene rapid evidence collection software”

- “defensive equipment reverse production software”

While Hafnium’s observed capabilities check some of these generic boxes, no one has previously reported the group’s capabilities against Apple devices.

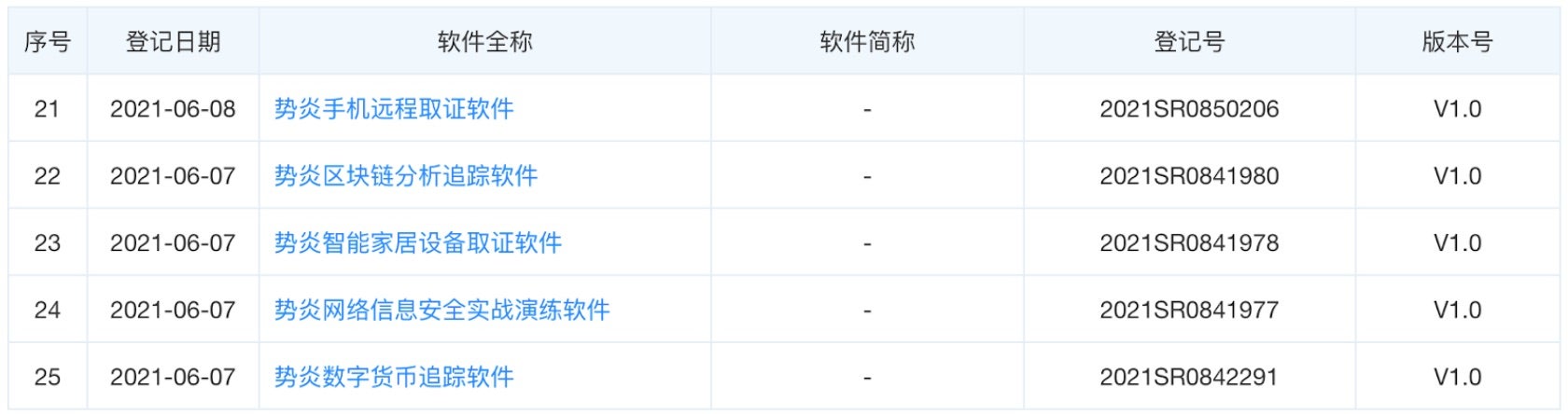

More recent patent filings from Shanghai Firetech, combined with the company’s history of working with the SSSB, suggests the company holds capabilities that may be useful in HUMINT operations. Capabilities like “intelligent home appliances analysis platform (2),” “long-range household computer network intelligentized control software (6),” and “intelligent home appliances evidence collection software (23)” could support close access operations against individuals. Other recent patents demonstrate that the firm still supports offensive cyber operations, such as “specially designed computer hard drive decryption software (13),”remote cellphone evidence collection software (21),” or “network information security actual confrontation practice software (24).”

Shanghai Firetech relationships with MSS offices beyond just the Shanghai Bureau may explain why some patented capabilities have not been observed to be associated with Hafnium tradecraft. While no public tenders or contracts were found, Shanghai Firetech likely offers offensive services to additional customers beyond Shanghai. The company maintains a subsidiary in Chongqing, Chongqing Firetech (重庆势炎信息科技有限公司). Chongqing Firetech is likely larger than its Shanghai-based mothership. In the summer of 2018, Chongqing Firetech opened positions for up to 25 college interns, including for a third office in Nanchang. Shanghai Firetech, by contrast, only paid insurance benefits on 32 full-time employees. It is unclear whether the absence of Chongqing Firetech from the indictment indicates that the company was not involved in activity attributed to the Hafnium cluster.

Conclusion

The combination of leaked chat logs from iSoon, the March 2025 indictments of Yin Kecheng and Zhou Shuai, and the July 2025 indictment Xu Zewei and Zhang Yu indicate that the Hafnium cluster consisted of at least three different companies. At least two of those persons, Xu Zewei and Zhang Yu, and their respective companies, Shanghai Powerock Network Co Ltd. and Shanghai Firetech Information Science and Technology Co Ltd, worked under the direction of the Shanghai SSB. Yin Kecheng likely worked alongside Xu and Zhang, though in what capacity–as an employee, subcontractor, or jointly-tasked by the SSSB–is unclear. Although Zhou Shuai is observed trying to sell Yin’s work through i-Soon, it is unknown what of Yin’s work, access, or tooling Zhou was trying to push.

The variety of tools under the control of Shanghai Firetech exceed those attributed to Hafnium and Silk Typhoon publicly. The findings underline the difficulty in successfully attributing intrusions to the organizations responsible for them. The capabilities may have been sold to other regional MSS offices, and thus not attributed to Hafnium, despite being owned by the same corporate structure. It is possible that none of the tooling uncovered by this report was ever deployed in offensive operations. Tooling for the remote control of home appliances, home computer networks, decryption of files, and remote mobile forensics do have commercial defensive applications. That said, we reasonably expect those tools to be advertised if sold for defensive purposes, and no such collateral exists.

Threat actor designations and naming conventions track clusters of behavior, not the organizations carrying out operations. Successful attribution resolves a campaign back to their actual operators, like Hafnium or Fancy Bear. This report finds there are very likely other campaigns and activities tracked under different names which can be attributed to Shanghai Firetech. The absence of their inclusion in the DOJ indictment of Zhang Yu and Xu Zewei may reflect a balance of equities on the part of the FBI, releasing in the indictment only what is popularly recognized as Hafnium and meets relevant legal thresholds while privately retaining intelligence of the company’s other campaigns and tooling.