Executive Summary

- I-Soon (上海安洵), a company that contracts for many PRC agencies–including the Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of State Security, and People’s Liberation Army–was subject to a data leak over the weekend of Feb 16th. It is not known who pilfered the information nor their motives, but this leak provides a first-of-its-kind look at the internal operations of a state-affiliated hacking contractor. The authenticity of the documents is still undecided. While the leak’s contents do confirm public threat intelligence, efforts to corroborate further the documents are on-going.

- The leak provides some of the most concrete details seen publicly to date, revealing the maturing nature of China’s cyber espionage ecosystem. It shows explicitly how government targeting requirements drive a competitive marketplace of independent contractor hackers-for-hire.

- I-Soon–whose employees complain about low pay and gamble over mahjong in the office–appears to be responsible for the compromise of at least 14 governments, pro-democracy organizations in Hong Kong, universities, and NATO. The leaked documents align with previous threat intel on several named threat groups.

- Victim data and targeting lists, as well as names of the clients who requested them, show a company who competes for low-value hacking contracts from many government agencies. The finding indicates that historical targeting information from Advanced Persistent Threats thought to be PRC contractors does not provide strong guidance on future targets.

- Machine translation enabled the rapid consumption of leaked data. These tools broadened the initial analysis of the information beyond seasoned China experts with specialized language skills and technical knowledge. This has enabled many more analysts to scan the leaked information and quickly extract and socialize findings. As researchers dig into the voluminous information, domain expertise will be required to understand the complex relationships and implicit patterns between the relevant organizations, companies, and individuals. One upshot is that geographically-specialized analysis will continue to provide distinct value, but the barrier to entry is much lower.

Initial Observations

- At 10:19 pm on January 15th, someone, somewhere, registered the email address [email protected]. One month later, on February 16th, an account registered by that email began uploading content to GitHub. Among the files uploaded were dozens of marketing documents, images and screenshots, and thousands of WeChat messages between employees and clients of I-SOON. An analyst based in Taiwan found the document trove on GitHub and shared their findings on social media.

- Many of the files are versions of marketing materials intended to advertise the company and its services to potential customers. In a bid to get work in Xinjiang–where China subjects millions of Ugyhurs to what the UN Human Rights Council has called genocide–the company bragged about past counterterrorism work. The company listed other terrorism-related targets the company had hacked previously as evidence of their ability to perform these tasks, including targeting counterterrorism centers in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

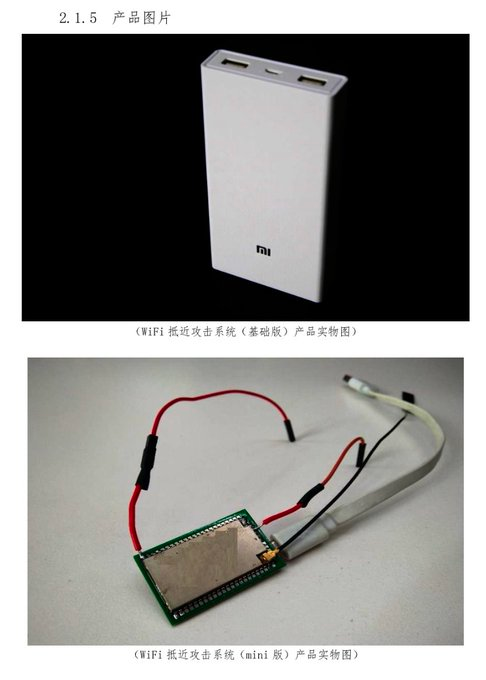

- Elsewhere, technical documents demonstrated to potential buyers how the company’s products function to compromise and exploit targets. Listed in the documentation were pictures of custom hardware snooping devices, including a tool meant to look like a powerbank that actually passed data from the victim’s network back to the hackers. Other documentation diagrammed some of the inner workings of I-SOON’s offensive toolkit. While none were surprising or outlandish capabilities, they confirmed that the company’s main source of revenue is hacking for hire and offensive capabilities.

- The leaked documents provide indicators–such as command-and-control infrastructure, malware, and victimology–which relate to suspected Chinese cyberespionage activities previously observed by the threat intelligence community. Initial observations point to activities spanning a variety of targeted industry sectors and organizations as well as APT groups and intrusion sets, which the threat intelligence community tracks, or has been tracking, as distinct clusters. The extent and strength of the relationships between indicators present in the leaked data and past intrusions are still subject to detailed evaluation.

- The selection of documents and chats leaked on GitHub seem meant to embarrass the company, but they also raise key questions for the cybersecurity community. One document lists out targeted organizations and the fees the company earned by hacking them. Collecting data from Vietnam’s Ministry of Economy paid out $55,000, other ministries were worth less. Another leaked messaging exchange shows an employee hacking into a university not on the targeting list, only for their supervisor to brush it off as an accident. Employees complained about low pay and hoped to get jobs at other companies, such as Qi An Xin.

Conclusion

The leaked documents offer the threat intelligence community a unique opportunity to reevaluate past attribution efforts and gain a deeper understanding of the complex Chinese threat landscape. This evaluation is essential for keeping up with a complex threat landscape and improving defense strategies.

Extensive sharing of malware and infrastructure management processes between groups makes high-confidence clustering difficult. As demonstrated by the leaked documents, third-party contractors play a significant role in facilitating and executing many of China’s offensive operations in the cyber domain.

For defenders and business leaders, the lesson is plain and uncomfortable. Your organization’s threat model likely includes underpaid technical experts making a fraction of the value they may pilfer from your organization. This should be a wakeup call and a call to action.