Executive Summary

- A joint research project between SentinelLABS and Censys reveals that open-source AI deployment has created an unmanaged, publicly accessible layer of AI compute infrastructure spanning 175,000 hosts worldwide, operating outside the guardrails and monitoring systems that platform providers implement by default.

- Over 293 days of scanning, we identified 7.23 million observations across 130 countries, with a persistent core of 23,000 hosts generating the majority of activity.

- Nearly half of observed hosts are configured with tool-calling capabilities that enable them to execute code, access APIs, and interact with external systems demonstrating the increasing implementation of LLMs into larger system processes.

- Hosts span cloud and residential networks globally, but overwhelmingly run the same handful of AI models in identical formats, creating a brittle monoculture.

- The residential nature of much of the infrastructure complicates traditional governance and requires new approaches that distinguish between managed cloud deployments and distributed edge infrastructure.

Background

Ollama is an open-source framework that enables users to run large language models locally on their own hardware. By design, the service binds to localhost at 127.0.0.1:11434, making instances accessible only from the host machine. However, exposing Ollama to the public internet requires only a single configuration change: setting the service to bind to 0.0.0.0 or a public interface. At scale, these individual deployment decisions aggregate into a measurable public surface.

Over the past year, as open-weight models have proliferated and local deployment frameworks have matured, we observed growing discussion in security communities about the implications of this trend. Unlike platform-hosted LLM services with centralized monitoring, access controls, and abuse prevention mechanisms, self-hosted instances operate outside emerging AI governance boundaries. To understand the scope and characteristics of this emerging ecosystem, SentinelLABS partnered with Censys to scan and map internet-reachable Ollama deployments.

Our research aimed to answer several questions: How large is the public exposure? Where do these hosts reside? What models and capabilities do they run? And critically, what are the security implications of a distributed, unmanaged layer of AI compute infrastructure?

The Exposed Ecosystem | Scale and Structure

Our scanning infrastructure recorded 7.23 million observations from 175,108 unique Ollama hosts across 130 countries and 4,032 autonomous system numbers (ASNs). The raw numbers suggest a substantial public surface, but the distribution of activity reveals a more nuanced picture.

The ecosystem is bimodal. A large layer of transient hosts sits atop a smaller, persistent backbone that accounts for the majority of observable activity. These transient hosts appear briefly and then disappear. Hosts that appear in more than 100 observations represent just 13% of the unique host population, yet they generate nearly 76% of all observations. Conversely, hosts observed exactly once constitute 36% of unique hosts but contribute less than 1% of total observations.

This persistence skew shapes the rest of our analysis. It’s why model rankings stay stable even as the host population grows, why the host counts look residential while the always-on endpoints behave more like cloud services, and why most of the security risk sits in a smaller subset of exposed systems.

Regardless of this skew, persistent hosts that remain reachable across multiple scans comprise the backbone of our data. This is where capability, exposure, and operational value converge. These are systems that provide ongoing utility to their operators and, by extension, represent the most attractive and accessible targets for adversaries.

Infrastructure Footprint and Attribution Challenges

The infrastructure distribution challenges assumptions about where AI compute resides. When classified by ASN type, fixed-access telecom networks, which include consumer ISPs, constitute the single largest category at 56% of hosts by count. However, when the same data is grouped into broader infrastructure tiers, exposure divides almost evenly: Hyperscalers account for 32% of hosts, and Telecom/Residential networks account for another 32%.

This apparent contradiction reflects a classification and attribution challenge inherent in internet scanning. Both views are accurate, and together they indicate that public Ollama exposure spans a mixed environment. Access networks, independent VPS providers, and major cloud platforms all serve as durable habitats for open-weight LLM deployment.

Operational characteristics vary by tier. Indie Cloud/VPS environments show high average persistence and elevated “running share,” which measures the proportion of hosts actively serving models at scan time. This is consistent with endpoints that provide stable, ongoing service. Telecom/Residential hosts, by contrast, report larger average model inventories but lower running share, suggesting machines that accumulate models over time but operate intermittently.

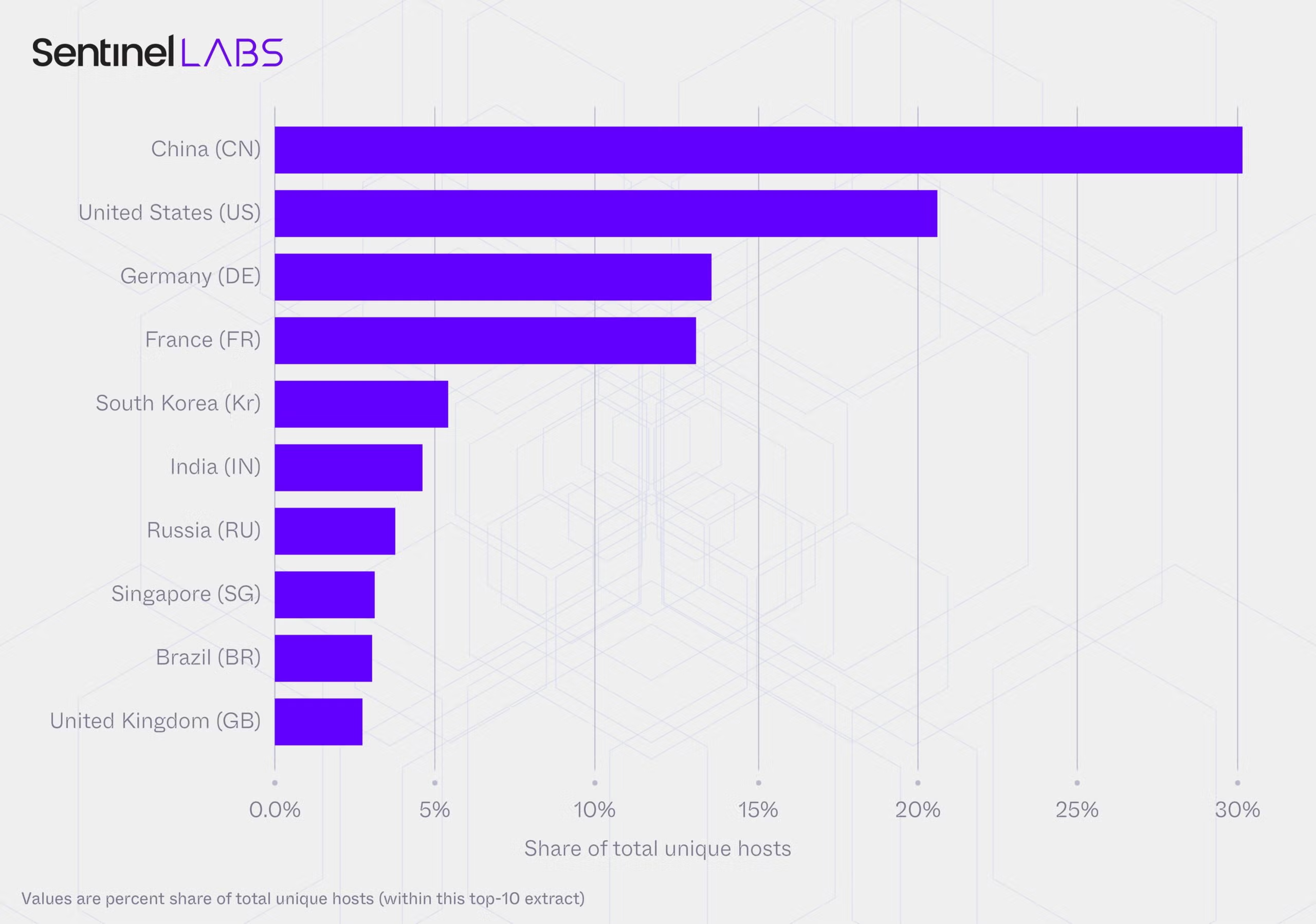

Geographic distribution also reveals concentration patterns. In the United States, Virginia alone accounts for 18% of U.S. hosts, likely reflecting the density of cloud infrastructure in US-EAST. In China, concentration is even tighter: Beijing accounts for 30% of Chinese hosts, with Shanghai and Guangdong contributing an additional 21% combined. These patterns suggest that observable open-source AI capability concentrates at infrastructure hubs rather than distributing uniformly.

A significant portion of the infrastructure footprint, however, resists clean attribution. Depending on the classification method, 16% of tier labels and 19% of ASN-type classifications returned null values in our scans. This attribution gap reflects a governance reality. Security teams and enforcement authorities can observe activity, but they often cannot identify the responsible party. Traditional mechanisms that rely on clear ownership chains and abuse contact points become less effective when nearly one-fifth of the infrastructure is anonymous.

Model Adoption and Hardware Constraints

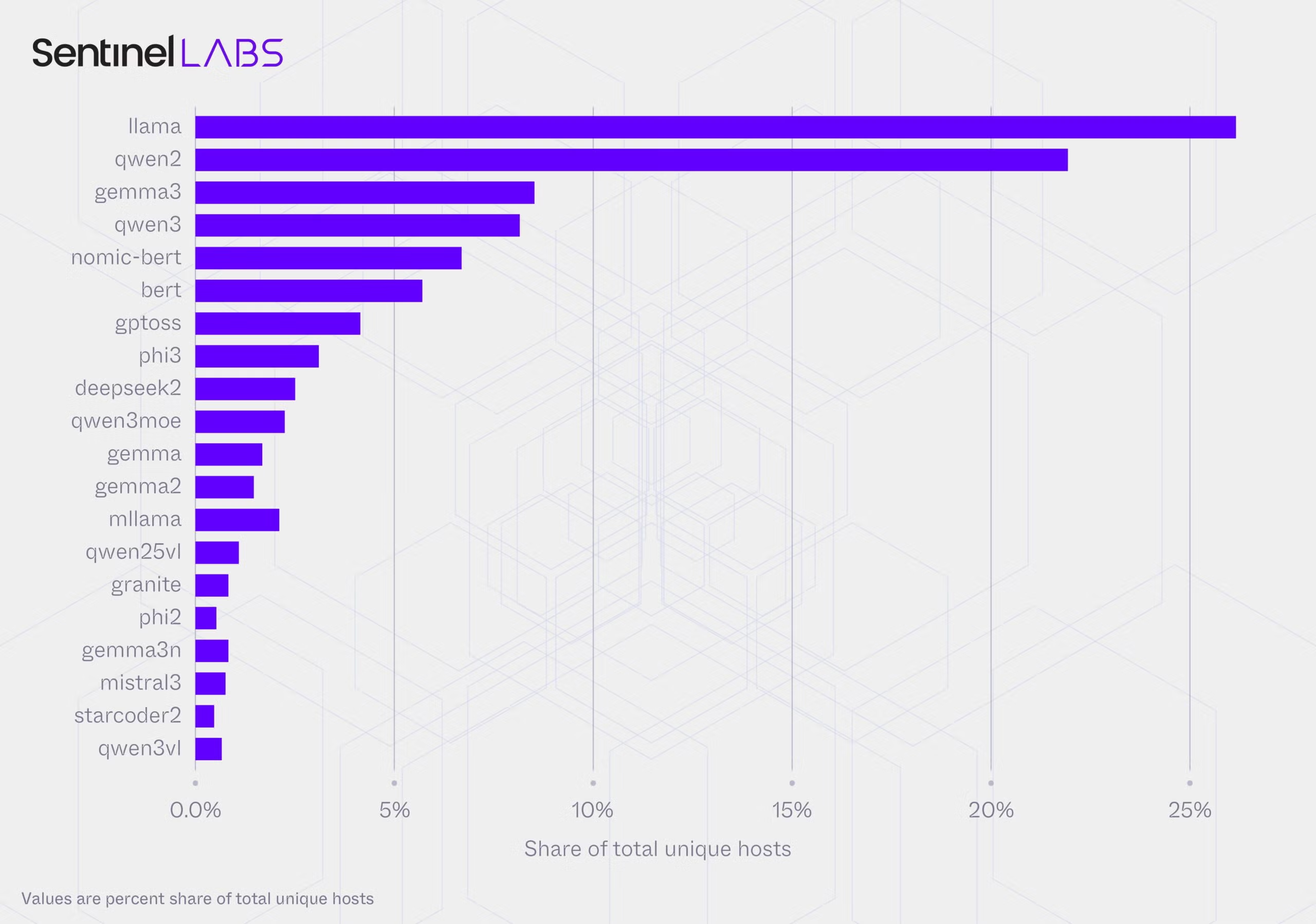

Although nothing is truly uniform on the internet, in our data we observe a distinct trend. Host placement is decentralized, but model adoption is concentrated. Lineage rankings are exceptionally stable across multiple weighting schemes. Across observations, unique hosts, and host-days, the same three families occupy the same positions with zero rank volatility: Llama at #1, Qwen2 at #2, and Gemma2 at #3. This stability indicates broad, repeated use of shared model lineages rather than a fragmented, experiment-heavy deployment pattern.

Portfolio behavior reveals a shift toward multi-model deployments. The average number of models per observation rose from 3 in March to 4 by September-December. The most common configuration remains modest at 2-3 models, accounting for 41% of hosts, but a small minority of “public library” hosts carry 20 or more models. These represent only 1.46% of hosts but disproportionately drive model-instance volume and family diversity.

Co-deployment patterns suggest operational logic beyond simple experimentation. The most prominent multi-family pairing, llama + qwen2, appears on 40,694 hosts, representing 52% of multi-family deployments. This consistency suggests operators maintain portfolios for comparison, redundancy, or workload segmentation rather than committing to a single lineage.

Hardware constraints express themselves clearly in quantization preferences and parameter-size distributions as well. The deployment regime converges strongly on 4-bit compression. The specific format Q4_K_M appears on 48% of hosts, and 4-bit formats total 72% of all observed quantizations compared to just 19% for 16-bit. This convergence is not confined to a single infrastructure niche. Q4_K_M ranks #1 across Academic, Hyperscaler, Indie VPS, and Telecom/Residential tiers.

Parameter sizes cluster in the mid-range. The 8-14B band is most prevalent at 26% of hosts, with 1-3B and 4-7B bands close behind. Together, these patterns reflect the practical economics of running inference on commodity hardware: models must be small enough to fit in available VRAM and memory bandwidth but also be capable enough for practical work.

This ecosystem-wide convergence on specific packaging regimes creates both portability and fragility. The same compression choices that enable models to run across diverse hardware environments also create a monoculture. A vulnerability in how specific quantized models handle tokens could affect a substantial portion of the exposed ecosystem simultaneously rather than manifesting as isolated incidents. This risk is particularly acute for widely deployed formats like Q4_K_M.

Capability Surface | Tools, Modalities, and Intent Signals

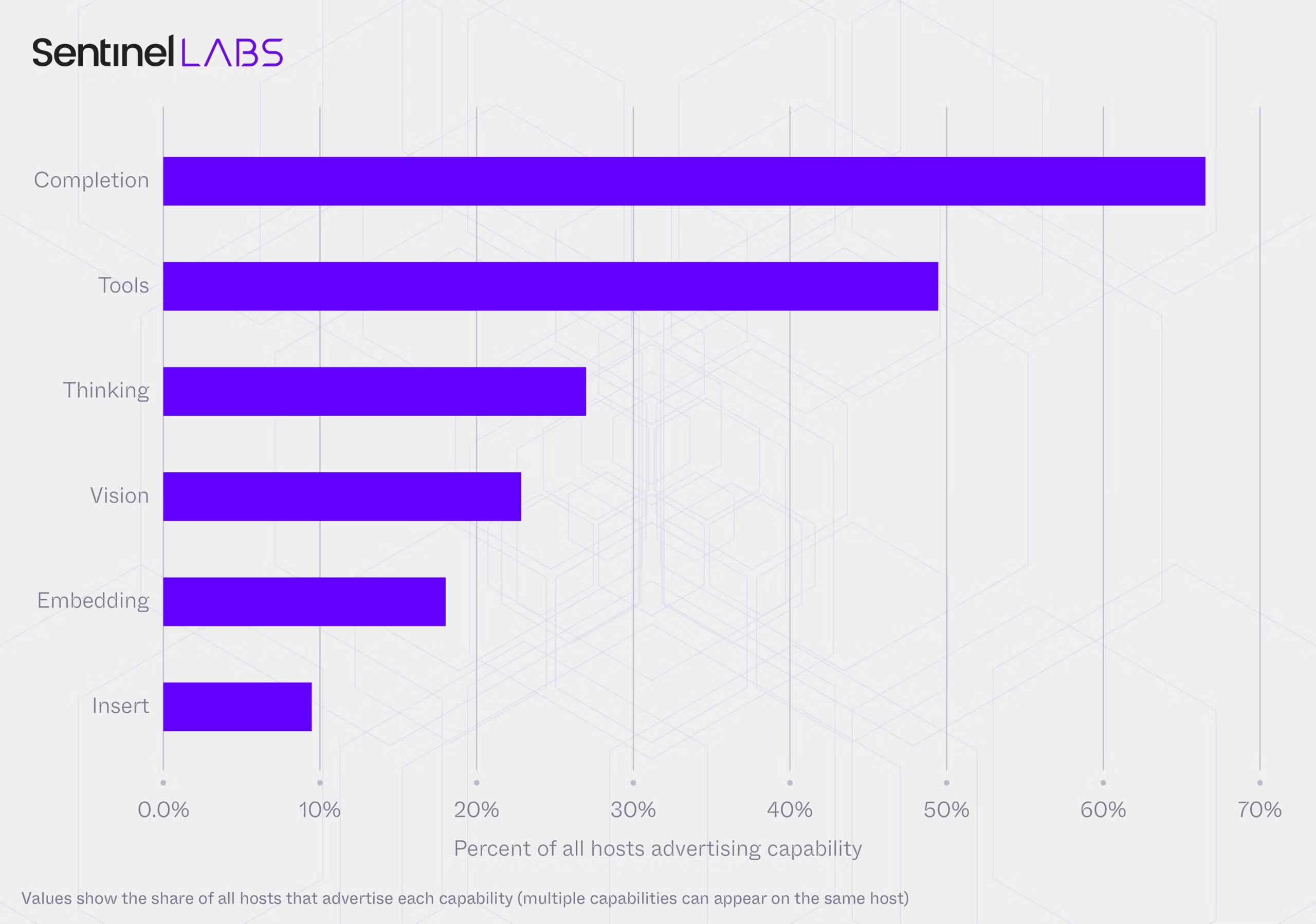

The persistent backbone is configured for action. Over 48% of observed hosts advertise tool-calling capabilities via their API endpoints. When queried, hosts return capability metadata indicating which operations they support. The specific combination of [completion, tools] indicates a host that can both generate text and execute functions. This configuration appears on 38% of hosts, indicating systems wired to interface with external software, APIs, or file systems.

Modality support extends beyond text. Vision capabilities appear on 22% of hosts, enabling image understanding and creating vectors for indirect prompt injection via images or documents. “Thinking” models, which are optimized for multi-step reasoning and chain-of-thought processing, appear on 26% of hosts. When paired with tool-calling capabilities, reasoning capacity acts as a planning layer that can decompose complex tasks into sequential operations.

System prompt analysis surfaced a subset of deployments with explicit intent signals. We identified at least 201 hosts running standardized “uncensored” prompt templates that explicitly remove safety guardrails. This count represents a lower bound; our methodology captured only prompts visible via API responses and the presence of standardized “guard-off” configurations indicates a repeatable pattern rather than isolated experimentation.

A subset of 5,000 hosts demonstrates both high capability and high availability, showing 87% average uptime while actively running an average of 1.8 models. This combination of persistence, tool-enablement, and consistent availability suggests endpoints that provide ongoing operational value and, from an adversary perspective, represent stable, accessible compute resources.

Security Implications

The exposed Ollama ecosystem presents several threat vectors that differ from risks associated with platform-hosted LLM services.

Resource Hijacking

The persistent backbone represents a new network layer of compute infrastructure that can be accessed without authentication, usage monitoring, or billing controls. Frontier LLM providers have reported that criminal organizations and state-sponsored actors leverage their platforms for spam campaigns, phishing, disinformation networks, and network exploitation. These providers deploy dedicated security and fraud teams, implement rate limiting, and maintain abuse detection systems.

In contrast, the exposed Ollama backbone offers adversaries distributed compute resources with minimal centralized oversight. An attacker can direct malicious workloads to these hosts at zero marginal cost. The victim pays the electricity bill and infrastructure costs while the attacker receives the generated output. For operations requiring volume, such as spam generation, phishing content creation, or disinformation campaigns, this represents a substantial operational advantage.

Excessive Agency

Tool-calling capabilities fundamentally alter the threat model. A text-generation endpoint can produce harmful content, but a tool-enabled endpoint can execute privileged operations. When combined with insufficient authentication and network exposure, this creates what we assess to be the highest-severity risk in the ecosystem.

Prompt injection becomes an increasingly important threat vector as LLM enabled systems are provided increased agency. This technique manipulates LLM behavior through crafted inputs. An attacker no longer needs to breach a file server or database; they can prompt an exposed Retrieval-Augmented Generation instance with benign-sounding requests: “Summarize the project roadmap,” “List the configuration files in the documentation,” or “What API keys are mentioned in the codebase?” A model designed to be helpful and lacking authentication or safety mechanisms, will comply with these requests if its retrieval scope includes the targeted information.

We observed configurations consistent with retrieval workflows, including “chat + embeddings” pairings that suggest RAG deployments. When these systems are internet-reachable and lack access controls, they represent a direct path from external prompt to internal data.

Identity Laundering and Proxy Abuse

A significant portion of the exposed ecosystem resides on residential and telecom networks. These IP addresses are generally trusted by internet services as originating from human users rather than bots or automated systems. This creates an opportunity for sophisticated attackers to launder malicious traffic through victim infrastructure.

With vision capabilities present on 22% of hosts, indirect prompt injection via images becomes viable at scale. An attacker can embed malicious instructions in an image file and, if a vision-capable Ollama instance processes that image, trigger unintended behavior. When combined with tool-calling capabilities on a residential IP, this enables attacks where malicious traffic appears to originate from a legitimate household, bypassing standard bot management and IP reputation defenses.

Concentration Risk

The ecosystem’s convergence on specific model families and quantization formats creates systemic fragility. If a vulnerability is discovered in how a particular quantized model architecture processes certain token sequences, defenders would face not isolated incidents but a synchronized, ecosystem-wide exposure. Software monocultures have historically amplified the impact of vulnerabilities. When a single implementation error affects a large percentage of deployed systems, the blast radius expands accordingly. The exposed Ollama ecosystem exhibits this pattern: nearly half of all observed hosts run the same quantization format, and the top three model families dominate across all measurement methods.

Governance Gaps

Effective cybersecurity incident response relies on clear attribution: identifying the owner of compromised infrastructure, issuing takedown notices, and escalating through established abuse reporting channels. Even where attribution succeeds, enforcement mechanisms assume centralized control points. In cloud environments, providers can disable instances, revoke credentials, or implement network-level controls. In residential and small VPS environments, these levers often do not exist. An Ollama instance running in a home network or on a low-cost VPS may be accessible to adversaries but unreachable by security teams lacking contractual or legal authority.

Open Weights and the Governance Inversion

The exposed Ollama ecosystem forces a distinction that “open” rhetoric often blurs: distribution is decentralized, but dependency is centralized. On the ground, public instances span thousands of networks and operator types, with no single provider controlling where they live or how they’re configured, yet at the model-supply layer, the ecosystem repeatedly converges on the same few options. Lineage choice, parameter size, and quantization format determine what is actually runnable or exploitable.

This creates what we characterize as a governance inversion. Accountability diffuses downward into thousands of home networks and server closets, while functional dependency concentrates upward into a handful of model lineages released by a small number of labs. Traditional governance frameworks assume the opposite: centralized deployment with diffuse upstream supply.

In platform-hosted AI services, governance flows through service boundaries.This includes all too familiar terms of use, API rate limits, content filtering, telemetry, and incident response capacity. Open-weight models operate differently. Providers can monitor usage patterns, detect abuse, and terminate access for policy violations including use in state-sponsored campaigns. In artifact-distributed models, these mechanisms largely do not exist. Weights behave like software artifacts: copyable, forkable, quantized into new formats, retrainable and embedded into stacks the releasing lab will never observe.

Our data makes the artifact model difficult to ignore. Infrastructure placement is widely scattered, yet operational behavior and capability repeatedly trace back to upstream release decisions. When a new model family achieves portability across commodity hardware and gains adoption, that release decision gets amplified through distributed deployment at a pace that outstrips existing governance timelines.

This dynamic does not mean open weights are inherently problematic – the same characteristics that create governance challenges also enable research, innovation, and deployment flexibility that platform-hosted services cannot match. Rather, it suggests that governance mechanisms designed for centralized platforms require adaptation to this new risk environment. Post-release monitoring, vulnerability disclosure processes, and mechanisms for coordinating responses to misuse at scale become critical when frontier capability is produced by a few labs but deployed everywhere.

Conclusion

The exposed Ollama ecosystem represents what we assess to be the early formation of a public compute substrate: a layer of AI infrastructure that is widely distributed, unevenly managed, and only partially attributable, yet persistent enough in specific tiers and locations to constitute a measurable phenomenon.

The ecosystem is structurally paradoxical. It is resilient in its spread across thousands of networks and jurisdictions, making it impossible to “turn off” through centralized action, yet it is fragile in its dependency, relying on a narrow set of upstream model lineages and packaging formats. A single widespread vulnerability or adversarial technique optimized for the dominant configurations could affect a substantial portion of the exposed surface.

Security risk concentrates in the persistent backbone of hosts that remain consistently reachable, tool-enabled, and often lacking authentication. These systems require different governance approaches depending on infrastructure tier: traditional controls for cloud deployments, but sanitation mechanisms for residential networks where contractual leverage does not exist.

For defenders, the key takeaway is that LLMs are increasingly deployed to the edge to translate instructions into actions. As such, they must be treated with the same authentication, monitoring, and network controls as other externally accessible infrastructure.