Executive Summary

- Salt Typhoon, first reported in September 2024, compromised over 80 telecommunications companies globally, facilitating an expansive intelligence collection effort that included intercepting unencrypted calls and texts, and breaching lawful intercept (CALEA) systems.

- The operation is tied to Yuyang (余洋) and Qiu Daibing (邱代兵), co-owners of companies named in the cybersecurity advisory and who worked closely to file patents and orchestrate the attacks.

- The hackers’ history traces back to the 2012 Cisco Network Academy Cup, where they excelled as students from a poorly-regarded university.

- The episode suggests that offensive capabilities against foreign IT products likely emerge when companies begin supplying local training and that there is a potential risk of such education initiatives inadvertently boosting foreign offensive research.

- In markets where foreign firms are given a fair shake at competition these initiatives still make sense. As China seeks to delete American-made IT from its tech stacks, these initiatives may present more risk than reward.

First publicly reported in September 2024, Salt Typhoon’s campaign is now known to have penetrated more than 80 telecommunications companies globally. The group’s campaign collected unencrypted calls and texts between US presidential candidates, key staffers, and many China-experts in Washington, DC.

However, Salt Typhoon’s collection activity went beyond those intercepts. Systems embedded in telecommunications companies for CALEA, which facilitates lawful intercept of criminals’ communications, were also breached by Salt Typhoon. A recent Joint Cybersecurity Advisory published by the U.S. and more than 30 allies sheds light on how Salt Typhoon came to penetrate global telecommunications infrastructure.

All of that high-tech novelty disguises a tale as old as time: skilled master trains apprentice, apprentice masters skills with tutelage, apprentice usurps the master owing to some core ideological difference between the two that festers over time. Gordon Ramsay’s feud with Marco Pierre White, Anakin’s rise under Obi-wan Kenobi, and Mao Zedong’s study of communism under Chen Duxiu all fit the mold.

This report adds Yuyang (余洋) and Qiu Daibing’s (邱代兵) and their history with the Cisco Networking Academy to the list of master-apprentice turned rivals narrative arc.

From Students to Operators

Qiu Daibing and Yuyang appear in various reports on companies named in the Salt Typhoon cybersecurity advisory. Both Qiu and Yu are co-owners of Beijing Huanyu Tianqiong, and Yu is also tied to another Salt Typhoon connected company, Sichuan Zhixin Ruijie. Qiu and Yu worked closely, filing patents together for work done at Beijing Huanyu Tianqiong.

Through their work at these firms, they hacked more than 80 telecommunications companies, facilitating one of the most expansive intelligence collection efforts of the last decade.

| Person | Company (Role) |

| Qiu Daibing | Beijing Huanyu Tianqiong (Shareholder 45% – Held through Sichuan Kala Benba Network Security Technology Company) |

| Yu Yang | Sichuan Zhixin Ruijie (Supervisor, Shareholder 50%) Beijing Huanyu Tianqiong (Shareholder 55%) |

Qiu and Yu’s personal history extends back at least 13 years before their companies would be named in the Cybersecurity Advisory.

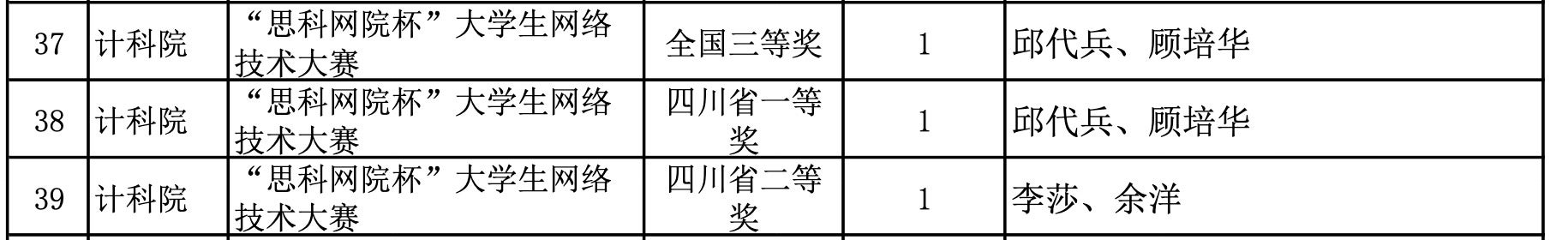

In 2012, the same names–Qiu Daibing and Yu Yang–appeared on different teams in the Cisco Network Academy Cup both representing their school, Southwest Petroleum University. Yu Yang’s team would win second place in Sichuan. Qiu Daibing’s team took first prize and eventually won third place nationally.

The data suggests this is not just some weird name collision and a case of mistaken identity. A database of 1.2 billion Chinese last names from 1930 to 2008 compiled by Bruce H.W.S.Bao at East China Normal University finds the last name “Qiu” (邱) is used by 0.27% of China’s population.

A second database of 30,282,623 first names from 1920-2019 shows a frequency of the first name “Daibing” (代兵) at a rate of 0.000845%. In other words, there are approximately 3,194 “Qiu Daibings” in China, or 0.000228% of the population. Yu Yang is a much more common name, so is less useful for trying to de-duplicate these characters.

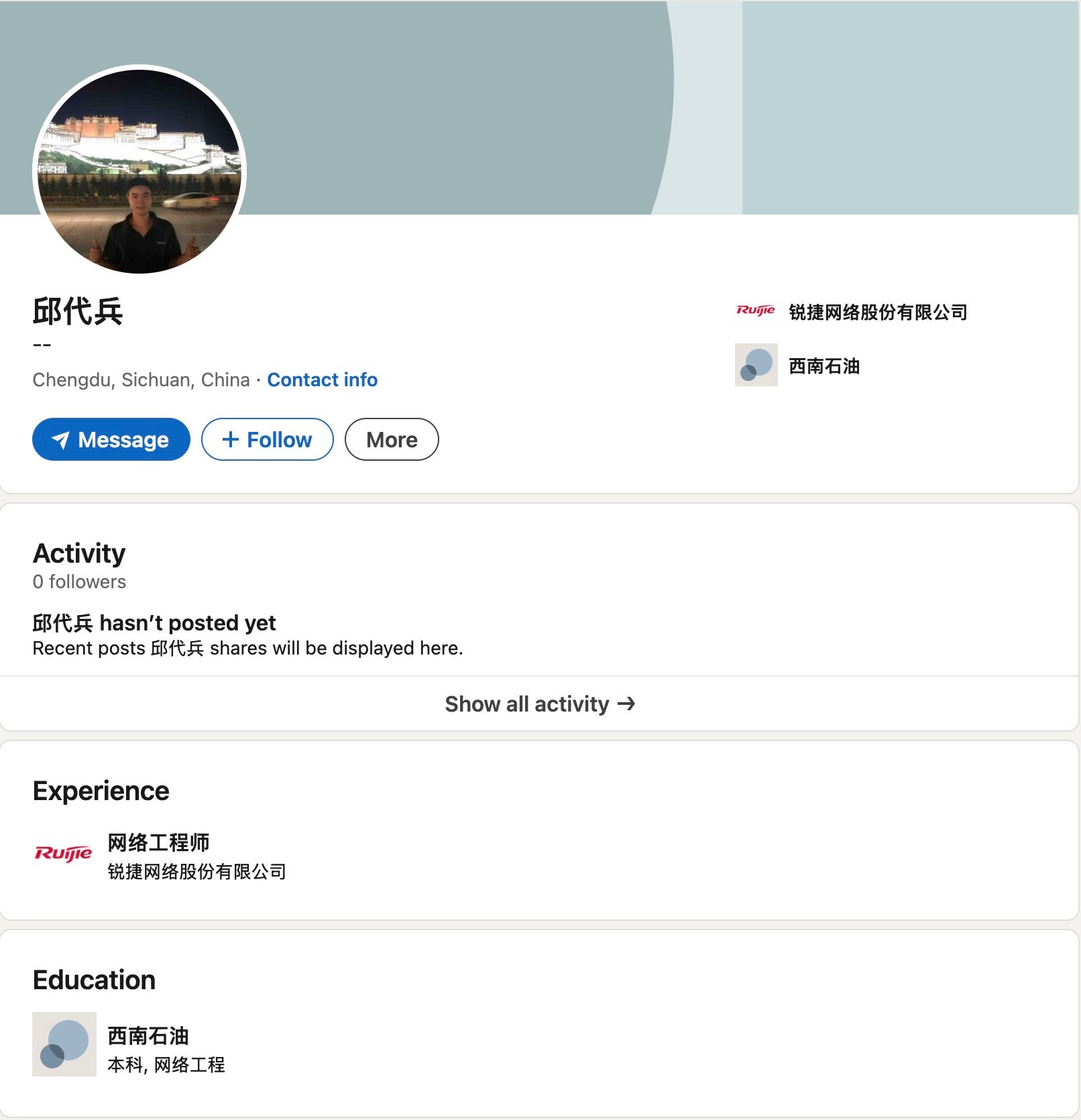

Qiu Daibing helpfully created a LinkedIn account. His education confirms that this person is the same Qiu Daibing who won the Cisco Network Cup competition as a SWPU student in 2012. But his employer is listed as Ruijie Network Company, not Sichuan Zhixin Ruijie. Why?

Qiu likely selected this much larger, well-known networking company in China with a partial name match simply because Sichuan Zhixin Ruijie is not a verified employer on LinkedIn. Although Qiu Daibing is not listed in corporate records as a shareholder of Sichuan Zhixin Ruijie, that absence of evidence does not preclude him from having been an employee at his friend Yu Yang’s company.

Alternatively, it is far less likely that two people with the same name, in the same province, in the same line of work, work at companies which have a partial name match. The odds of that happening? Even less than 0.000228%.

This, combined with other circumstantial evidence, like their alma mater being located in the same province as the companies registered to individuals of the same names, their career trajectories being related to the same field of study, and the apparent enduring relationship between the two across patent and corporate registration data, suggests that the Qiu Daibing and Yu Yang associated with the companies in the Salt Typhoon CSA are almost certainly the same Cisco Cup winners from 2012.

The World is Flat and Anyone Can Cook

The Cisco Network Academy began in 1997 and entered China’s market in 1998. Among the content covered in Cisco networking academy were many of the products Salt Typhoon exploited, including Cisco IOS and ASA Firewalls.

Of course, a product training academy educating students on the company’s wares is hardly surprising. More notable is the fact that two students from a regional university, with limited recognition in IT and cybersecurity education participated in the Cisco Network Academy and went on to run one of the most expansive collection operations against global telecommunications firms ever detected and disclosed publicly.

Southwest Petroleum University is not a beneficiary of China’s efforts to professionalize and harmonize the country’s offensive cyber talent pipeline. SWPU is a Double First-Class institution, meaning the university is in the top 150 schools in the country, but it has relatively few accolades for its cybersecurity and information security programs.

The Ministry of Education’s China Academic Degrees and Graduate Education Development Center gives the school’s Computer Science and Technology degree its lowest rating of C-. The school’s software engineering program scores a few points higher with just a C rating.

Qiu Daibing and Yu Yang are all the more remarkable given SWPU’s apparently unremarkable cybersecurity education.

The duo’s participation in Cisco Network Academy and excellence in the Cisco Academy Cup, given the lack of excellent education at their alma mater, underlines what the author considers one of the best parts of the cybersecurity community–as the line from Ratatouille goes, “Anyone can cook.”

Cisco Network Academy has trained more than 200,000 students in China since the roll out of its program in the late 90s. No doubt that other graduates have gone on to participate in offensive operations against its products, but the vast majority do not. The program itself is not cause for concern, nor should participation in it be construed as such.

Lessons from the Kitchen

Instead, the episode of Qiu and Yu should highlight to defenders, policymakers, and the offensive hacking community a few key findings. First, offensive cyber capabilities against foreign-made IT products likely extends to whenever those companies entered the market and began supplying training to locals. As a result, China likely had some offensive capabilities against Cisco products by the early 2000s. This dynamic exists for most countries where such training takes place, not just the PRC.

Second, hiring processes for cybersecurity roles should emphasize demonstration of technical competencies, similar to coding interviews for software engineers, as the university degree may itself be a modest indicator of potential success in the workplace. China does an excellent job emphasizing hands-on learning for cybersecurity students. Other countries should follow suit.

Finally, some offensive teams may benefit from putting employees through similar product academies offered by firms manufacturing targeted products–like Huawei’s ICT academy.

Conclusion

Like other master-apprentice rivalries, the betrayal of Qiu and Yu was based on ideology and, ultimately, nationality. Qiu and Yu are not an oddity; they are evidence of a world in which today’s students can become tomorrow’s rivals with little more than time, opportunity, and a different notion of whose security they serve.

Their path to attacking Cisco products also raises the spectre of more widespread capability against western ICT products than previously acknowledged. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, the PRC pushed the line of “China’s peaceful rise” with the help of influence operations of the Ministry of State Security. With money on their mind and a rapidly growing market, most western technology companies set up shop in China and moved to train new talent on their products and systems. The result was a boon to sales and growth over the following 20 years.

Only in hindsight, and with the story of Qiu and Yu, can security researchers now see how those efforts may have incidentally boosted offensive researchers. Microsoft’s sharing of source code with the MSS has long been touted as a Faustian bargain by the security community. Education initiatives fall short of such acclaim, but may come to present more risk than return as the Chinese Communist Party remakes the country’s computer networks with home-grown technology–as the Delete America document makes clear is their goal.

All third-party product names, logos, and brands mentioned in this publication are the property of their respective owners and are for identification purposes only. Use of these names, logos, and brands does not imply affiliation, endorsement, sponsorship, or association with the third-party.